Writers beware: Reading this journalist’s reflections on life may cause extreme jealousy

In his latest book, ‘The Lede,’ Calvin Trillin reflects on decades of reporting — and reveals some of his more colorful interactions with fellow titans of journalism

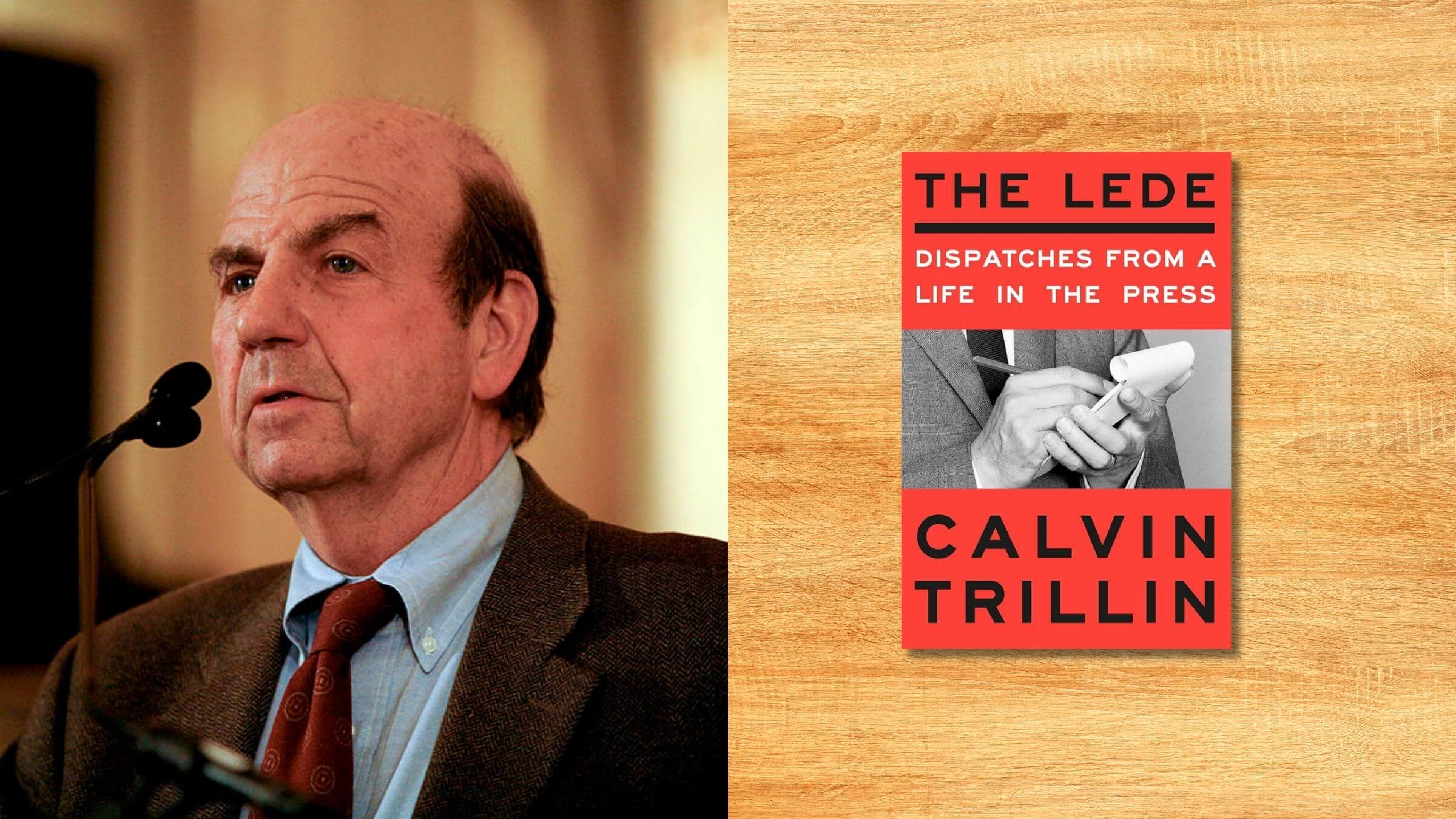

Trillin, who made his name covering the Civil Rights Movement and the American South, published his most recent book in February. Photo by Getty Images, Random House

Calvin Trillin is a literary hyphenate. During a career that’s spanned over six decades, he’s written over 30 books and numerous essays and long-form journalism pieces, not to mention his humor columns and doggerel political poetry. Especially annoying to us mere mortals, he does it all exceedingly well, with rare grace, finesse and an eye for the tiniest of detail.

His latest book —The Lede: Dispatches From a Life in the Press — is a collection of pieces that bear some relationship to journalism. As he notes in his introduction, he was fortunate to have “the freedom to write about what engaged me.”

Here you’ll find profiles of John Irving Bloom, a respected Dallas film critic, who took on the persona of Joe Bob Briggs to review drive-in movies. The collection also includes moving tributes to departed journalists such as Morley Safer, Murray Kempton and Russell Baker. Trillin goes out in search of the best BBQ in Texas and discusses the history of his relationship with The Nation. (More on that later.)

For me, this excerpt from a 2003 profile of New York Times journalist R.W. Apple encapsulates Trillin’s style and skills:

“Apple famously sees to his early morning tasks … while ensconced in one of the brightly striped night shirts made for him by Harvie & Hudson, of Jermyn Street, the same firm that makes his dress shirts, so that a house guest not yet fully recovered from a late night at the Apple table can be startled by the impression that a particularly festive party tent had somehow found its way indoors.”

In just one sentence, we learn that Apple is something of a dandy, a little taken with himself, and overweight — and Trillin communicates these details with a seemingly effortless, almost poetic flair that captures the essence of his subject far better than a camera. We even discover who makes Apple’s pajamas.

Trillin’s career began in Kansas City, Missouri. Unlike many Jews from Eastern Europe, Calvin’s paternal grandfather landed in Galveston, not New York City. While Trillin initially believed this decision had to do with the “stubbornness” for which his family was “still renowned,” he eventually learned that his grandfather was a beneficiary of the Galveston Movement. Bankrolled by prosperous American Jews such as Jacob Schiff, the Galveston Movement was an attempt to move impoverished Eastern European immigrant Jews out of New York City, where they were a potential embarrassment to their more established brethren.

The discovery sparked an article Trillin wrote for the inaugural issue of Moment magazine, which posed a burning question: “Who is Jacob Schiff that he should be embarrassed by my Uncle Ben Novsky?”

In any event, the family settled first in St. Jo, Texas, before moving to Kansas City. Calvin’s father, Abe, who was just 2 years old when he arrived in this country, was less concerned with Calvin being a Jew than being an American.

“He wanted me to be president of the United States,” Trillin writes. “His fallback position was that I not become a ward of the court.”

The family was largely secular, though Trillin has memories of attending Rosh Hashanah services with his father and grandfather, who would spend the trip home from synagogue arguing about the quality of the cantor. Having read a book called Stover at Yale and learned that this was the university where wealthy American industrialists sent their sons, Abe was determined that Calvin attend. Not only did Trillin get into Yale, he became chairman of the student newspaper, the Yale Daily News. Henry Luce, the founder of Time, had once held the same position, and the connection helped Trillin land a job at the magazine, where he initially covered the American South.

“It was a very busy year on what was sometimes called the seg beat,” Trillin reflects in The Lede. He covered the integration battle, returned to the magazine’s New York headquarters and eventually — through a friend — met with William Shawn, the venerable New Yorker editor. Trillin was planning to return to the south to write a book about the integration of the University of Georgia, and wanted to pitch freelance stories generated from his research. Shawn was interested, but suggested Trillin write as a staff writer, a position he’s held ever since, writing features as well as what used to be called casuals (now Shouts and Murmurs).

Enter the late Victor Navasky — or as Trillin referred to him, “the wily and parsimonious Victor Navasky.” Trillin had contributed a couple of pieces to Monocle, a humor magazine that Navasky ran while attending Yale Law School. When he took over the liberal Nation, he offered Trillin a humor column. What Navasky didn’t know is that writing this column was destiny for Trillin. He had been cracking jokes — some of them unwanted — since sixth grade Sunday school, when he realized that by taking on the role of class clown, he could “get lucky” and “get kicked out of class and miss the rest of the course.”

While the idea of a Nation column intrigued him, the negotiations did not. Navasky offered a rate in the high two figures. Trillin’s agent countered with the low three figures. Ultimately, that is what they settled on: the very low — the lowest — three figures. As Trillin put it, in one fell swoop, Navasky transformed “The Nation from a shabby pinko sheet to a shabby pinko sheet with a humor column.”

That eventually morphed into a syndicated humor column and a stint as the “Deadline Poet,” a position he still holds at the magazine. Most recently, for example he wrote:

As he lumbers from trial to trial,

Exuding great volumes of bile,

He says, “Can’t you see:

They’re picking on me.”

Self-pity was always his style.

But of course, man cannot live on bread and low-three-figure paydays alone. Trillin’s mainstay — and the subject of his book — is journalism. The Lede, its title, refers to the journalistic term for the introduction of a story — a sentence or paragraph designed to entice readers to continue. Trillin quotes several, including one from James Thurber, who, when an editor thought an obituary he’d written suffered from wordiness, resubmitted the story like this:

“Dead.

“That’s what the man was when they found him with a knife in his back at 4 p.m. in front of Riley’s saloon at the corner of 52nd and 12th streets.”

Or this from crime-reporter-turned-novelist Edna Buchanan, who covered a death that occurred at Church’s, a fast food restaurant, when a customer who waited in a lengthy line only to get to the counter and discover the store was out of fried chicken. Then came fisticuffs and a shot from a security guard. Wrote Edna: “Gary Robinson died hungry.”

Or this from Trillin himself: “In 1993, when The New Yorker for the first time ran a photograph of a bare breasted actress, a subscriber wrote me to express, outrage, and what happened to a magazine, once known for its elegant, understated prose. The only defense I could think of was that they were small breasts, so you could say that the tradition of understatement was still alive.”

Trillin’s skills are a gift, like a Steph Curry three-pointer, an innate skill that can’t be taught. As a writer, I of course appreciate them. And I hate him. How’s that for a lede?

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO