Author has ‘The Soul of Judaism’ — and the DNA to prove it

Bruce Haynes, the grandson of the National Urban League’s founder, discovers his forebear was half-Jewish

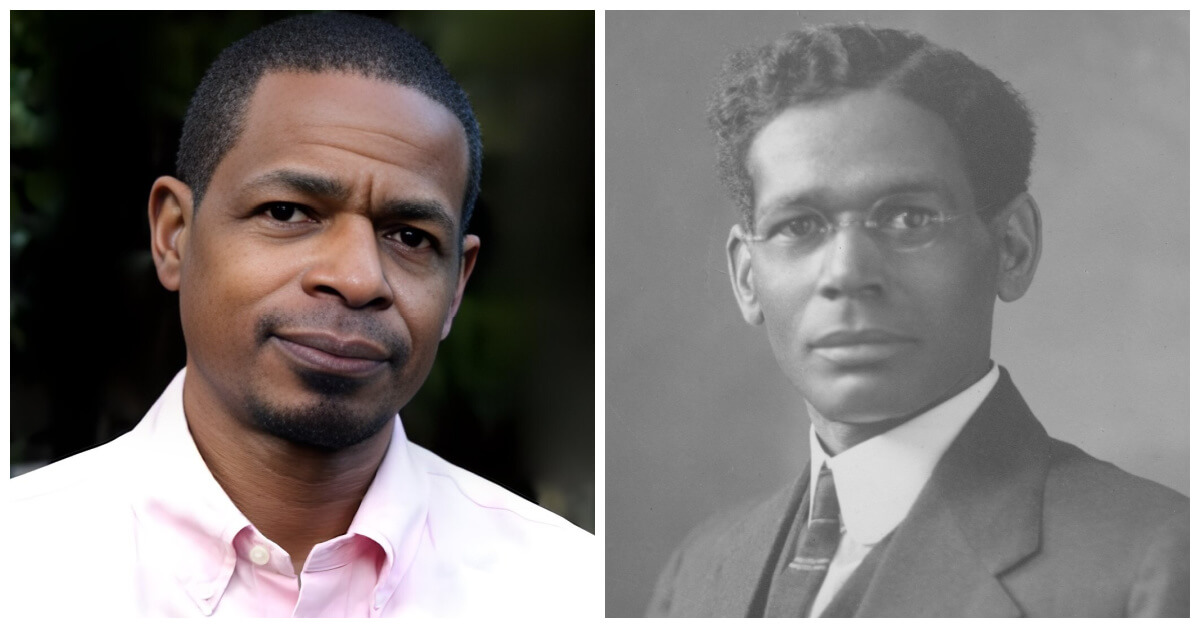

Bruce Haynes, left, and his grandfather George Haynes. Courtesy of Bruce Haynes

Although Bruce Haynes is the author of The Soul of Judaism — arguably the most definitive book about Black Jews in the U.S. written in the last 20 years — his initial interest in the subject wasn’t because he was Jewish himself.

A sociology professor at the University of California, Davis, Haynes grew up in an African American family that practiced various denominations of Protestantism. Yet there were always curious, if unexplained, connections to Judaism: His father seeking out a rabbi to talk to near the end of his life; the family’s ownership of a building leased to a Jewish fraternity at the City College of New York; and Bruce’s own placement in predominantly Jewish private schools. Add to that his marriage to an Ashkenazi Jewish woman.

Last spring, those pieces fell together when he received his DNA analysis from Ancestry.com.

“They said I was 33% Nigerian, 15% Scottish, 15% Ivory Coast, and 14% Jewish,” he said.

“It compared my DNA matches to other people in their database,” leading to a Jewish common ancestor named Louis Altheimer, who lived in Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

“Guess where my grandfather George Haynes was from? Pine Bluff, Arkansas.”

Haynes, 63, was quite knowledgeable of his grandfather, who secured a place in history as the co-founder of the National Urban League with white suffragist Ruth Baldwin. What he hadn’t known was that George, born in Pine Bluff in 1880, was the son of Louis Altheimer. Newfound family genealogical accounts support the DNA report, indicating that Altheimer, who emigrated from Germany to Ohio in 1863 and settled in Arkansas after the Civil War, had a child with a Black woman named Mattie Sloan.

That was Bruce Haynes’ great-grandmother. She and Altheimer did not marry one another; the laws and customs of the South would have prohibited it. Instead, she married an African American man named Louis Haynes, whose surname was given to George.

Altheimer also married, bringing to Arkansas a Jewish bride from Germany, but fathered additional children outside his marriage. That led to other lines of African American descendants, some of whom did take on the Altheimer name.

After learning of his grandfather’s parentage, Bruce Haynes made contact through Ancestry.com with a whole string of cousins he never knew he had.

“They said they always knew there had been a half-brother,” he said of his welcome-to-the-family conversations.

While George Haynes, who left Arkansas, had been lost to them, the Black Altheimer descendants were well-aware of their white cousins who remained in the state. Louis Altheimer and his brothers were immigrant success stories, running several enterprises and leaving their name on a town not far from Pine Bluff.

And the white and Black Altheimers had cordial relations, Haynes said he learned from his newly connected cousins. As a social scientist specializing in race, he said that sort of acknowledgement from white relatives is not typically the case.

“Everybody in town must have known that these kids were related to him, and the families took ownership of that relationship. At no point have I heard that the white Altheimers denied it,” he said.

Also notable are the circumstances of their creation in the first place. While Louis Altheimer’s relationships with working class Black women may not have been equal, Haynes said, it certainly wasn’t the same as abuses committed by slaveholders a generation before.

“We don’t know what the power dynamics of these relationships were. But we do know they came in the context of a free society, post-slavery, where Black women would have had more agency,” said Haynes.

While he plays catch-up with a new set of relatives, Haynes digests what his Jewish ancestry means — both to him personally and to history. It’s worth a rewrite of textbooks to note that the co-founder of one of the major Black civil rights groups was half-Jewish.

Haynes also draws comparisons to one of the Black Jewish icons featured in his book: Julius Lester, whose maternal great-grandfather, Adolph Altshul, was also a German Jewish immigrant to Arkansas. Unlike Altheimer, Altshul lived with his common-law Black wife, Maggie Carson, who again, he would not have been permitted to marry.

Lester famously “reverted” to Judaism in 1982, which he documented in his book Lovesong. In it, he writes of being the only Altshul descendant in the United States, Black or white, left practicing Judaism.

So is Haynes, who with his wife has long been a member of a synagogue, considering joining — or rejoining — the tribe now that his lineage has been established?

He’s noncommittal on that. But for the real answer, look to his soul — of Judaism.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO