In a universe of rigid rules and unsanctioned passions, everyone’s a heretic

Jay Michaelson rewrote his debut short story collection — multiple times — before deciding it was ready to enter the world

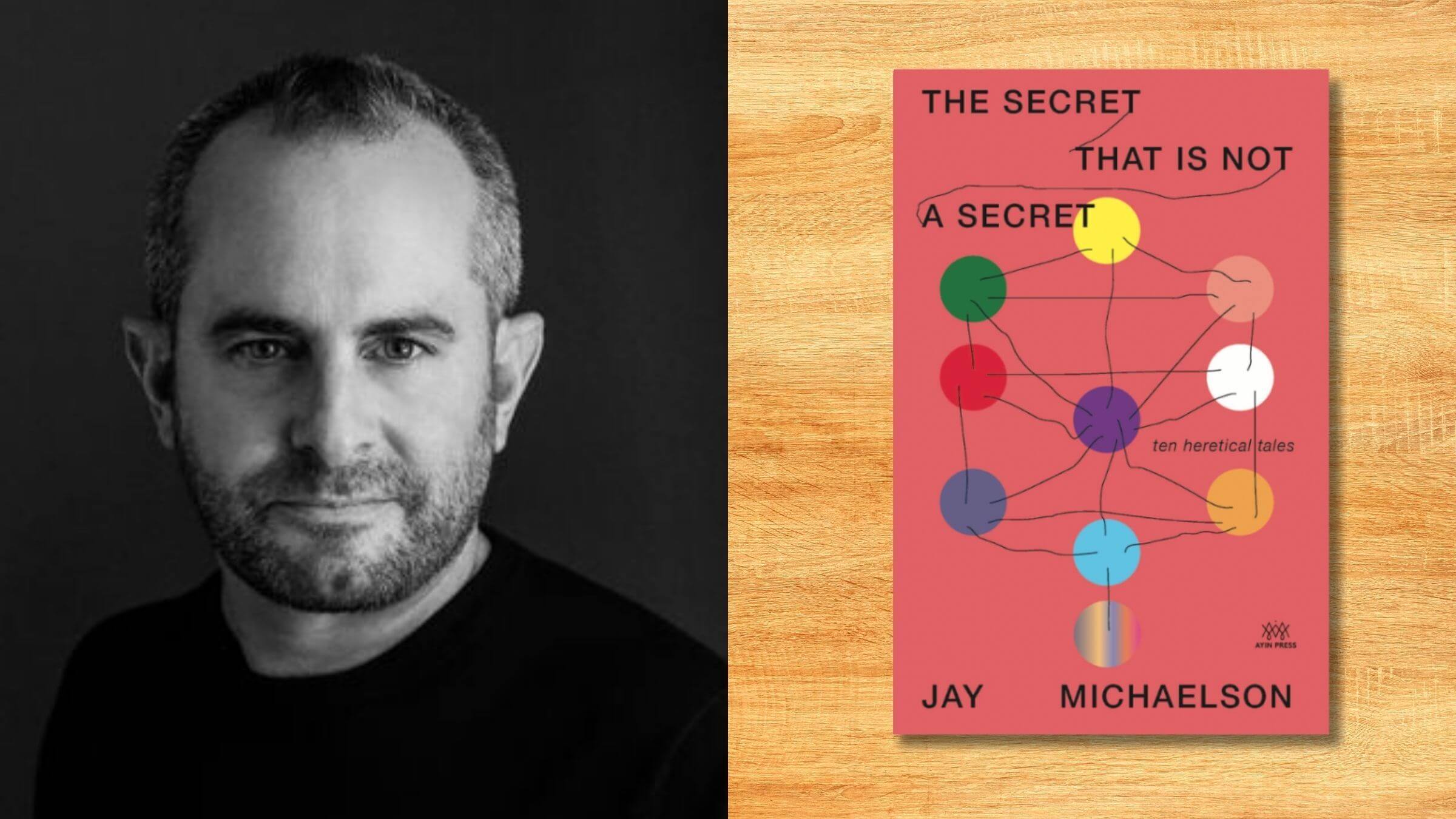

The Secret That is Not a Secret is Jay Michaelson’s first work of fiction. Photo by Beowulf Sheehan, Ayin Press

A Chabad housewife who can’t stand her husband’s beard. A gay mindfulness guru disturbed by his secret sexual fantasies. An observant Israeli teenager plagued by ominous visions of a dreamy classmate.

What unites these very different characters from Jay Michaelson’s debut short story collection, The Secret That Is Not a Secret: Ten Heretical Tales, is their inability to reconcile their own innermost desires with the prevailing norms of romance in their respective communities. Many of Michaelson’s protagonists are gay Haredi Jews, who must suppress their identities in order to survive within a strict and insular society. Yet even the characters enjoying thriving queer partnerships in the secular world confront shames similar to those of their more religious brethren; and even the straight characters (or, in some cases, the characters who think they’re straight) find themselves stifled and unfulfilled by their relationships.

These shared concerns reflect Michaelson’s desire to demystify aspects of the Haredi world, like strict rules governing sexual behavior, that are often exoticized in secular literature. They also represent his expansive concept of queerness, which he described broadly as the feeling of not fitting into the “boxes” — social, emotional, psychological — that any society imposes on its members.

I reached Michaelson (who is also a Forward contributor) at his home outside New York City to talk about the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, the challenges of writing the Haredi world and the actual meaning of the word “heretic.” This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve written many nonfiction books, but this is your first foray into short stories. How did you wind up writing this collection?

A lot of nonfiction writers consider ourselves to be failed novelists. My heroes growing up were all great novelists, and that’s what I thought “real” writing was. I went so far as to get an MFA in order to learn I wasn’t primarily a fiction writer. I wrote the first drafts of these stories almost 20 years ago, rewrote them during my MFA, and then again during the last year.

What changes did you make in order to feel like the stories were ready for publication?

When I wrote the first version of this collection in my 20s, I was a lot more like some of my characters: Orthodox, closeted and really conflicted and repressed. Etymologically, the heretic is the one who chooses beyond the boundaries of what’s allowed or not allowed. A lot of the productive heresy of the book was discovering the non-truthfulness of a lot of religious secrets. It took me a while to find that out for myself.

Why did you decide to set these stories largely in the Hasidic world?

For me, the Hasidic characters represent an intensification of what many of us feel, even if we’re not religious. Their lives involve a more intense form of the conflicts between conforming to a community and expressing one’s individuality. Between my academic study of Hasidism and living adjacent to that world for several years, I got to know it well enough. But a lot of my early readers were super helpful, even in the little things like remembering what Chabad kids call their parents.

Each story in this collection is accompanied in the table of contents by an attribute from the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. Tell me about that idea and why it was important to you.

Kabbalah is an amazing mythic system which responds to boring philosophical monotheism by saying that God is actually changing all the time, and has these different potencies and powers that become predominant at different times. I wouldn’t say I believe that this describes something true about the universe. But Hamlet also doesn’t describe something true about the universe. It’s just this amazing poetic creation of imagination.

The Tree of Life is based on the 10 sefirot, or personalities of God. This is a concept that evolved in the 12th and 13th centuries. The stories provide a twist on those qualities: there’s also a story about anger which is aligned with Gevurah, which is the embodiment of the divine when there’s anger present.

In some of the stories, the connection to the sefirot isn’t that explicit. For example, “The Secret of Nakedness,” in which a secular gay man named Nathan examines what he sees as illicit sexual desires, is linked to Tiferet, which to my understanding has nothing to do with sex.

In the metaphor of the Tree of Life, Tiferet is the trunk, or the span connecting upper and lower. That’s what this story does for me; it crystallizes questions about the relationship between sexuality and spirituality, desire and faith. And it’s the story where these questions are talked about most explicitly.

It’s interesting that Nathan, who doesn’t come from a religious background and lives openly and happily with his partner, is grappling with the same issues around his sexuality as the collection’s closeted Haredi characters.

What I did not want was to draw an easy dichotomy between repressed religious people and liberated non-religious people. Nathan is modern, he’s out, he has a partner and that’s the dream, right? But he’s still struggling with his desires, he’s struggling with what he believes to be a conflict between his spirituality and sexuality.

Was queer romance always a big part of this story collection?

I’m very interested in the queerness we all experience, across different gender identities and sexual orientations. Even the first story — about a Hasidic woman who can’t stand her husband’s beard — is a queer story. The protagonist is dealing with a lot of issues around masculinity and femininity and her own desires, even though she’s not an explicitly gay character. For me, one of the ways to say what queerness is, is that all of us are put into boxes, and none of us fit those boxes. Someone could be a heterosexual cisgender person and still find a misfit between what society says about gender roles and one’s own self.

In some of my nonfiction books, I go into the queerness of Jewish heroes. It’s not about whether these biblical characters — for example, Ruth and Naomi — were “doing it,” but rather, how they expressed their desires in a way that subverted the patriarchy and made it work for them. In a social context where women were disempowered by society, here are two women who found a way to thrive.

A lot of fiction about Haredi Jews is marketed towards a secular audience and at least implicitly confirms that the secular lifestyle is the right one. Whereas in your book, many Haredi characters are explicit in their scorn for the secular world, regardless of what freedoms they might personally covet. Why was that important to you?

To me, that’s the liberation of fiction. I’m not even buying into their perspective, but just saying what it is. I have a lot of critiques of power structures in Haredi communities, and the way education is given or not given; I don’t want to whitewash anything. But there’s a pull to that community — and other religious communities as well. Evangelical Christians might decide the presidential election, right? So it would be helpful to get a more nuanced understanding of what evangelicals want, rather than saying, “These people are all repressive and horrible. I’m going to go back to my latte and pretend they don’t exist.”

Do your observations of other highly religious communities affect your writing about Haredi Jews?

I try not to map one group onto another, but I’m really interested in fervent religion; I love apocalyptic beliefs and cults. My previous book was about a heretical movement in 18th-century Poland. I’ve had Shabbat dinner in Chabad houses where they believe that the dead rebbe is the messiah and keep a suitcase ready to go in case he comes right now and they have to run for the door. I don’t know if they objectively believe that’s possible, and I’m glad I don’t have that belief. But I’m fascinated by it.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO