If you thought her first bat mitzvah was trailblazing, wait till you hear about her second

At 83, Ruth Messinger stepped up to the bimah — just like she did 70 years ago

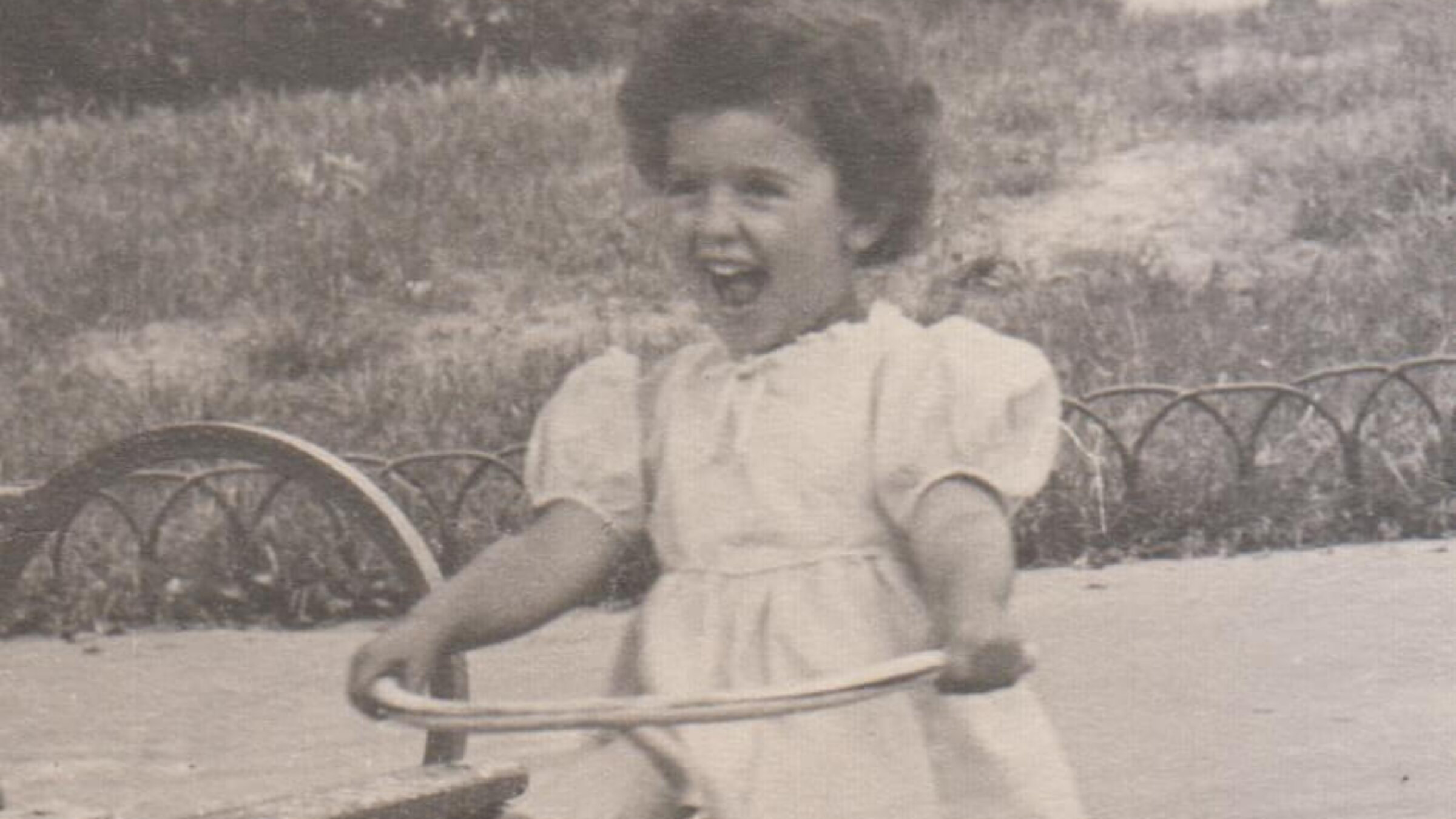

A young Ruth looks ahead to a life filled with triumph, activism, and a pair of bat mitzvahs. Courtesy of Ruth Messinger

The Saturday morning at SAJ, a Reconstructionist synagogue just a few steps away from Central Park, seemed to begin like any other. Outside, it was a bright and unseasonably warm December day, as congregants and guests began filtering in. Below a stained glass window on one side of the room, chairs had been reserved for the bat mitzvah and her family members. However, the guest of honor in this case wasn’t a newly minted teenager celebrating a rite of passage into adulthood, but an octogenarian. And she was marking not her first bat mitzvah but her second.

Ruth Messinger, 83, had the first-ever bat mitzvah at Park Avenue Synagogue back in 1953, and last weekend became the first congregant to celebrate the nascent contemporary ritual of a second bat mitzvah at SAJ, where Messinger has been a member for half a century.

During the decades she’s been part of the SAJ community, Messinger pursued a career in politics as a city council member, Manhattan borough president, and the first woman Democratic nominee for mayor, earning more than 40% of the vote against Republican incumbent Rudy Giuliani in 1997. She later served for nearly 20 years as the president of the American Jewish World Service — a nonprofit that seeks to fight poverty and pursue justice in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean — and has continued to advocate for social justice and human rights, including at her own celebration.

Messinger dedicated her second bat mitzvah to her late mother, the woman who’d made her first one happen at a time when any bat mitzvah was still barrier-breaking. And she could barely contain the smile that kept spreading across her face throughout the day as she honored her mother and shared the occasion with four generations of family, from her sister down to her great-grandchildren.

“I loved the weekend. Awed by my family, their performances, and their love. And overwhelmed by the rabbi,” she told me in a note afterward. A day and a half later, she said, “I am still flying high.”

A social justice Jew from the very beginning

Both of Messinger’s parents grew up Jewish. “But when they met and married, they resolved to create a home that was more consistently Jewish, whatever that meant to them,” she said. They didn’t keep kosher and their level of observance might be described as “modest,” she said, but they marked all the holidays, took their synagogue membership very seriously, sent Ruth to Hebrew school, and were active along with her grandparents in Jewish social service organizations.

That last part has shaped Messinger’s conception of Judaism for the rest of her life. “When people ask me, ‘What denomination are you?’ I sometimes say, ‘Social Justice,’” she said. “My early family teaching — and obviously it took — was Judaism is a faith and has beliefs,” she explained, but “the most important thing about being Jewish is how you live in the world and how you take care of other people, Jews and non-Jews.” In other words, “Judaism is about doing things for other people.”

Messinger’s mother, Marjorie Wyler, was immersed in Judaism professionally, too. She took a job at the Jewish Theological Seminary shortly before Ruth was born and worked in public relations there for over 50 years. She was involved in and eventually became the executive producer of The Eternal Light radio and television programs that made Jewish learning more broadly accessible. Wyler was also a pioneer in making domestic violence and the environment Jewish issues, for example, and otherwise connected Judaism to advocating for social justice and mending the world.

Though Messinger never knew all the details, she can say for sure that it was her mother who set the stage for her to become the first bat mitzvah at Park Avenue Synagogue, where the family belonged at the time. Wyler was likely influenced by Mordecai Kaplan and early Reconstructionist bat mitzvahs, including the first public bat mitzvah celebration in the country, which was held for Kaplan’s daughter, Judith, at SAJ in 1922.

Wyler approached the Park Avenue rabbi, Milton Steinberg, years in advance with another family, the Wimpfheimers, to ask for bat mitzvahs for their daughters. And though Steinberg died before the occasion arrived, Ruth became part of an unofficial cohort of girls around the country who were the first bat mitzvahs at their congregations.

She recalled being teased mercilessly by the boys in the bar mitzvah class until her mother found the two girls a tutor instead. She remembered the search for a fancy dress for an awkward adolescent who didn’t know how to wear one very well. She can’t forget showing up at her Orthodox great-grandfather’s apartment to do her chanting for him, since he didn’t travel on Shabbat and couldn’t walk well enough to make it to the synagogue for her ceremony. “That frankly had some power for me,” Messinger said. “I’m sure this is not a man who ever thought about bat mitzvah, thought only about bar mitzvah, but I think he took pride in me.”

And then there was the coincidence of her haftarah reading. “By random pick of the time near your birthday, my haftarah was Amos, which is all social justice,” she said. “So that was the first thing I studied seriously, it was the first sort of drash talk I gave, and it seems to have stuck for my whole life.”

Being a first took on more significance over the years as Messinger strove to break down barriers for women in general and delved into work in the Jewish community.

“Judaism is both an ancient faith and an evolving faith, and one of the things it’s done in a variety of ways is to increasingly recognize the role and power of women,” she said. “I’d like anything that will promote the notion among women that, A. They have many trailblazers to point to in history, and B. They still have their work in front of them.”

Planning a second simcha

The digital invitation to Messinger’s second bat mitzvah included a crash course for the uninitiated. “The contemporary custom of a second celebration is based on life beginning anew at 70,” it read, pointing to Jewish texts that describe 70 as “the fullness of years.” If we start over at 70, then turning 83 means celebrating a second bat mitzvah.

Messinger said she does not necessarily feel like her life began anew at 70 — “my life has just continued to be like one wildly crazy, wonderful life,” she said. “I try to slow down, but I don’t seem to be doing a very good job.” But the idea nevertheless appealed to her and she took it to the cantor at SAJ, who said they’d never done a second bat mitzvah before, but why not try?

“I think about this as a nice age marker. I’m lucky to be here, I’m lucky to be healthy, and I’m particularly lucky to have this wonderful family,” Messinger said. “And the fact that my family is significantly — especially for modern comparative times — Jewish in various ways that are meaningful to me and to them, and that I know would mean a lot to my mother, is part of the impetus for doing this.”

And when Messinger asked who in the family would be willing to read Torah or haftarah portions for the service, all three of her children — who are Reconstructionist, Reform, and Modern Orthodox — and several of her grandchildren signed up, while additional family members participated and helped with other aspects of the event.

“It felt important to be able to help create the dream she had about lots of members of our family really being involved [in the] service,” said granddaughter Amani Ariel-Wamala, who agreed to read Torah even though she hadn’t done so since her own bat mitzvah 15 years ago. Ariel-Wamala and her mom, Messinger’s daughter Miriam Messinger, also helped edit and design the program, which featured a dedication and a list of quotes from sources including Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, Audre Lorde, Howard Zinn, and John Lewis. These texts, Messinger wrote, “have helped to define how I understand myself, my faith, and my obligation to work in the world for justice.”

Miriam agreed that her mom has hardly slowed down, including in planning and even baking for her own event. “She’s not somebody who rests on her laurels. She works more than I’m sure you or I do probably put together on any given day,” she said. But that’s all the more reason to pause and mark this occasion, she said. “It’s always just a great opportunity to celebrate her and to thank her for what she’s doing.”

Messinger said that, when the synagogue asked what the big cake they were ordering should have written on it, Miriam suggested, “She’s just getting started.”

A ‘repository of ethics and wisdom’

The din of chatter at SAJ on Saturday morning was punctuated with excited hellos as people arrived, weaving through the aisles to offer greetings and hugs. By the time the service started with music and prayer, Messinger was already beaming, looking back at her family gathered behind her. That smile returned every time a family member made their way to the bimah to read a few verses, say a prayer, or carry a Torah scroll, followed by hugs and kisses as they returned to their seats.

In a blessing, Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Herrmann called Messinger “a living Torah, a repository of ethics and wisdom,” and “a deep source of inspiration,” and called on her to look back with pride at her accomplishments. She wished for her to feel a sense of sipuk, or satisfaction, and to look ahead at “years of strength, vitality, health, increased wisdom — which is probably not possible — and joy.” At her mention of “a lifetime of sweetness,” the crowd tossed wrapped gummy candies at Messinger, who laughed with her whole body at the sugary barrage. Soon she was lost among people singing and dancing and surrounding her with joy.

“Today is about legacy,” she said in her own remarks, speaking about her mother and her first bat mitzvah, about the new minhag or custom of the second bat mitzvah, and about her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. “I love the ways in which they are stepping up and exceeding the passions of their forebears, the ways in which each of them does work for justice and remembers as well to love mercy, practice kindness, and walk humbly.”

She talked about justice, too, nodding to Amos from her luck-of-the-draw 1953 haftarah as “a prophet who railed against evil, denounced privilege, and called for ‘justice to roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream,’” and sharing insights and lessons from decades of dedication to justice and human rights.

She concluded with a quote from psychologist Eva Fogelman, who wrote a book about Holocaust rescuers and would end her talks by saying: “I know many of you will come up to me and say that you cannot imagine what you would have done in those situations. When you say that to me, I will say to you, ‘The question is not what you would have done, but what are you doing.’”

And when she was done, the gathered crowd rose to give Messinger a standing ovation.

Celebrating Ruth

“I always love hearing her speak,” Lylah Messinger, Ruth’s granddaughter and one of the day’s Torah readers, told me as guests streamed out of the service and upstairs for the kiddush luncheon.

Upstairs in the hallway, Messinger’s college friend Minna Schrag echoed some of the same sentiments. “I’m just so proud of her,” she said, adding that she felt Messinger’s remarks were just right, “beginning with her emphasis that if you want to help people, you have to listen to them.”

Inside a large room beyond the hallway, there were several tables in the center holding noshes for the midday crowd. Some guests sat at other tables around the perimeter of the room and many milled about eating and chatting as Messinger made her rounds and kids toddled, ran, and played.

“People know her for her grand contributions and huge acts, as a huge force for change in the macro world,” said granddaughter Francesca Sternfeld, who lives with Messinger and has had her help raising her young son from the very beginning. “I see her close up with incredible capacity to notice, to meet someone where they are, to show up for them. And so I’m the mother of a kid that kind of got the whole potential of Ruth all to himself, which is an incredible thing,” she added. “I’m just honored to be part of her tribe.”

When I approached Tamara Fish — who does work on diversity and inclusion in Jewish communities and had been seated up front at the morning’s service — she joked that she and Messinger “have a mutual admiration society.” They’ve been friends for at least seven years, and Fish considers Messinger a generous, insightful, and supportive mentor.

“Every now and then when you’re doing work on racial justice, it’s such a slog and it’s so fraught with frankly retribution, that sometimes you’re like, ‘Should I even bother?’ To celebrate Ruth, who has absolutely no other way of being … is a celebration of a type of fire that never dies,” Fish said. “So just being in her aura, and also having it be a celebration, is a nice way of saying, ‘Get off your ass and get to work.’”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO