Leonard Bernstein was far more Jewish than you’d know from ‘Maestro’

The composer and conductor’s Judaism is core to his music, and his life

Bernstein, conducting the New York Philharmonic in the 1970s. Courtesy of Getty Images

Maestro, the new Leonard Bernstein biopic, is not, in fact, a biopic. At least not in any traditional sense. Though this is a movie about a creative genius and the charismatic face of classical music in the latter half of the 20th century, we see little of Bernstein’s biography, his creative process or, even, his music.

The missing music is related to another omission: Bernstein’s Judaism.

Bernstein grew up in an Orthodox home outside of Boston to Russian-Jewish immigrants, and fell in love with music at his Conservative synagogue, Mishkan Tefila, thanks to organist and choirmaster Solomon Braslavsky. And he was proud of his Judaism, as the one scene in the film that addresses Bernstein’s Jewishness shows; despite being prompted by mentor Serge Koussevitzky, he refused to change his name to Burns to sound less Jewish.

But particularly, his Jewishness was woven into much of his music. And without highlighting Bernstein’s music — which appears almost exclusively as background scoring, recognizable to only to those who already know it — Maestro loses so much of who Bernstein was, how he understood himself, and how he understood his role in the world.

“I think that’s one of the things that’s really important within the context of Bernstein,” said Judah Cohen, a professor of Jewish studies and musicology at Indiana University; we spoke over Zoom, along with his colleague, Constance Cook Glen, a teaching director and professor in the Jacobs School of Music at IU. “To see how fluently Judaism was part of his vocabulary, how he saw the world, and how he communicated with the world.”

Obvious or subtle — still Jewish music

“The Jewish music that he learned from Braslavsky appears a minimum of 20 times in music that Bernstein wrote,” said Cantor David. F. Tilman, 79, who studied conducting under Bernstein’s producer and longtime friend, Abe Kaplan, at Juilliard, before embarking on his cantorial career; he met Bernstein several times.

“That’s where it clearly begins for Bernstein,” Tilman continued. “He played that organ in that synagogue and he learned gobs and gobs of Jewish musical stuff, and all of those musical influences seeped into him.”

Bernstein himself also said he was inexorably drawn to biblical material. “I mean I keep coming back to it. I’ve written two works in the last 10 years,” he said in a 1967 interview with art critic John Gruen. “And one was Kaddish and one is the Chichester Psalms — they’re both biblical in a way. So obviously something keeps making me go back to that book.”

Some of Bernstein’s Jewish and biblical references are quite overt, including major works such as Bernstein’s first symphony, Jeremiah; his third, Kaddish; his ballet, Dybbuk, based on the classic Yiddish theater play by the same name; the Chichester Psalms, which is entirely in Hebrew; and numerous smaller works such as a setting of the Hashkivenu Shabbat prayer and the flute piece Halil, which means “flute” in Hebrew and commemorates fallen Israeli soldier and flautist Yadin Tenenbaum.

But more subtle references abound, found in musical themes that draw from Jewish ritual or even just notations in the score; sometimes, the time signatures themselves are drawn from gematria, a form of Jewish numerology.

Jeremiah, which Bernstein first conceived of as an idea titled “A Hebrew song,” is inspired by the titular biblical prophet, who predicted great destruction and disaster. The biblical book of Lamentations, which Bernstein used for the Hebrew text of the third movement’s soprano solo, expresses the prophet’s sorrow that his prophecies came true.

But it’s not just the words and themes that come from Jeremiah; the tunes do too.

“What’s so wonderful about the Jeremiah symphony is, in the second movement, he takes the melodies that everybody uses to chant Haftarah on Shabbat morning,” Tilman said. “It’s clearly based on the chanting mode for chanting Haftarah in Ashkenazic congregations.” The soprano solo, Tilman said, also uses the cantillation from Lamentations.

Other works contain small, but distinctive, tips of the hat to Judaism.

For example, West Side Story, which was originally conceived as East Side Story, the tale of a conflict between Catholic and Jewish gangs, instead of Puerto Rican and white ones, still contains Jewish elements.

“How does West Side Story open? That’s Tekiah!” Tilman said, singing the musical’s distinctive opening motif, which imitates the shofar blast heard each Rosh Hashanah. “It’s not even subtle.”

Tilman also pointed out a line in Candide, Bernstein’s politically edgy musical adaptation of the Voltaire novel. The song “I Am Easily Assimilated” on its surface already describes the diasporic Jewish experience throughout history. But, taking it further, the character even says she is from “Rovno Gubernya,” the region in Ukraine where Bernstein’s father was born.

Bernstein originally called the song “The Old Lady’s Jewish Tango.” And, riffing on the classical musical tempo markings of allegro or vivace, Bernstein marked the piece “hassidicamente.”

Bernstein’s theologies and politics

Kaddish, and Bernstein’s theatrical piece Mass, written for the opening of the Kennedy Center, use biblical texts as a way for the composer to air and grapple with his religious and political beliefs.

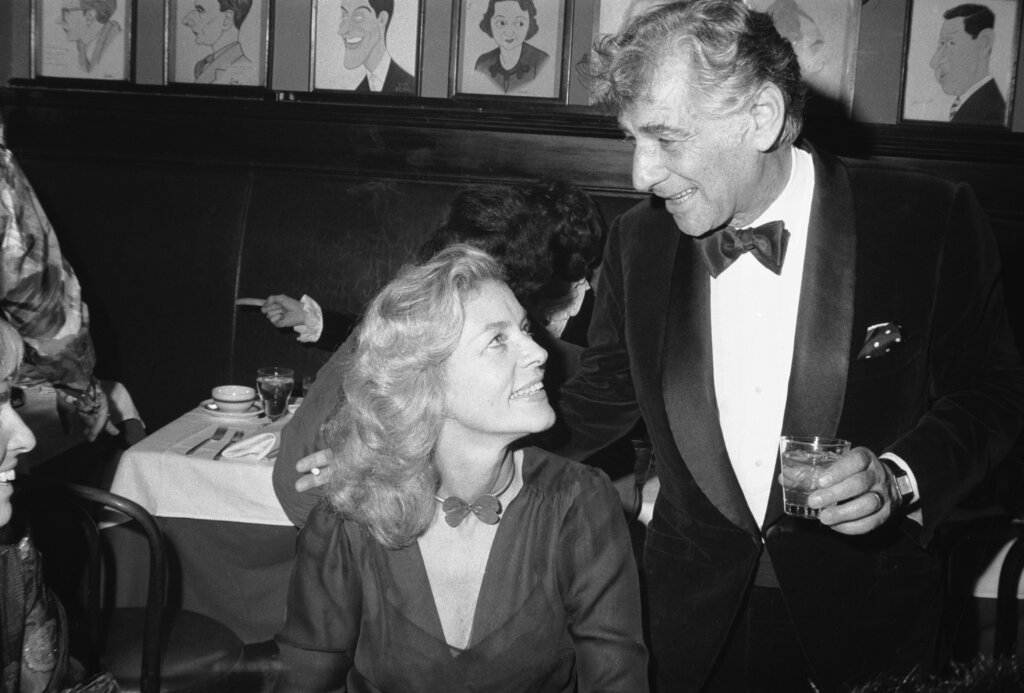

Kaddish, a deeply personal symphony for choir, orchestra, soloists and narrator, was dedicated to John F. Kennedy, who had just been assassinated. In it, as the choir sings the full Aramaic text of the Jewish prayer for the dead, a narrator, speaking in English, struggles with God even while praising him. (Bernstein’s wife, Felicia, originally read the narration.)

The narration repeatedly makes the parallel, tortured relationship between father and son, and God and humanity, clear.

With Amen on my lips, I approach

Your presence, Father. Not with fear,

But with a certain respectful fury.

Even after Kaddish premiered, Bernstein continued to work on it, writing in letters to friends and his sister that the piece was too personal for him to work with a poet or lyricist. He needed to write the narration himself.

“He has a tremendous argument with God, which many people find too strong or maybe even blasphemous, but which is in the old Judaistic tradition,” Bernstein said of the narrator in a 1985 interview with Japan’s NHK station. “All our great Judaistic personalities of the past, including Abraham, who founded Judaism, and Moses, and the prophets, all argued with God.”

Bernstein’s Mass, meanwhile, takes a less overtly Jewish angle on the idea of arguing with a beloved God. A controversial theatrical piece for “singers, players and dancers” inspired by the Catholic ritual, it includes rock and jazz elements while also drawing from the Western classical tradition — and throwing in a few Hebrew lines.

“I see it as such an ecumenical approach to faith, that I don’t see it as very different from his other works,” said Cook Glen, from the Jacobs School of Music. “We see these very deeply ingrained parts of Jewish history — the screaming at god.”

Mass is also a deeply political piece, grappling with, in part, the Vietnam War, and rooted in ideas about questioning authority. It was so controversial at the time that Richard Nixon, then president, conspicuously skipped the performance, afraid it would embarrass him.

Politics were part of many of Bernstein’s works. His Candide, already a political farce in Voltaire’s version, took on the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Red Scare that was in full swing in the 1950s — increasing scrutiny on many Jews, including Bernstein, who was the subject of an FBI file for decades. Though he never finished it, he had begun work on a “Holocaust opera” tentatively titled Babel, and many of his pieces, including Kaddish, deal with the new knowledge of the atrocities of the Nazis as information began to emerge in the wake of the war.

Bernstein also took strong political stances on issues such as civil rights and the Vietnam War, which he expressed through political activism as well as his music.

“As an American and as a Jew, I know that religious liberty and civil liberty go hand in hand. Destroy one and you endanger the other,” he wrote in a 1970 letter to the Connecticut Jewish Ledger about hosting a fundraiser for the Black Panthers.

But Bernstein saw his music as a vehicle through which to express his desire for peace. Sometimes, as he wrote, he used the warring between an atonal 12-tone musical mode and a tonal one to symbolically express the peaceful resolution he desired for the world; other times, like in the Chichester Psalms, he did so by combining different religious traditions.

He was “saying ‘well, we have the Psalms in common, so no matter what language we sing them in, they’re a place where we can have this conversation,’” Cook Glen said.

Bernstein and Israel

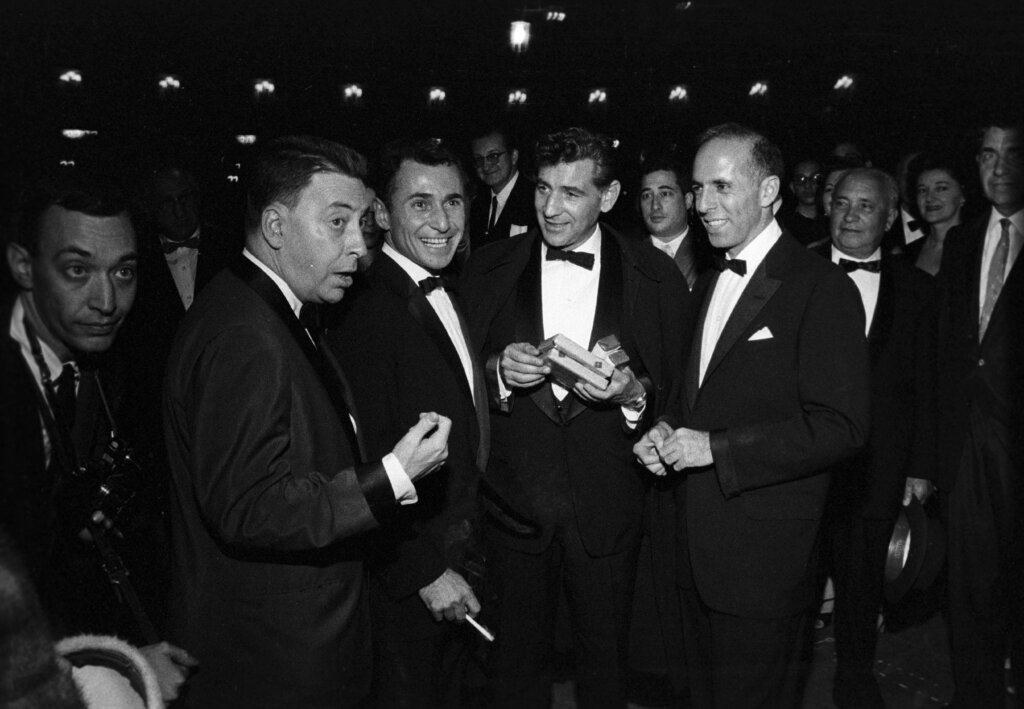

Bernstein began conducting the Israel Philharmonic in 1947 — before the country’s official founding, when it was the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. He conducted special concerts for the army during Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, often in the midst of air raids, and went on to conduct 25 seasons with the orchestra.

Later, after the conclusion of the 1967 War, Bernstein conducted a historic concert in the Roman Theater on Mount Scopus, to celebrate the capture of Jerusalem from the Jordanians. The Israel Philharmonic performed “HaTikvah,” the Israeli national anthem, and played Bernstein’s favorite work to conduct: Mahler’s Second Symphony, The Resurrection — a symbolic choice. (This piece, and Bernstein’s famous performance of it with the London Symphony Orchestra at the Ely Cathedral in England, is the only scene showing Bernstein conducting at length in Maestro.)

“He saw Israel as being a very important force in his life. This was something that he saw as a kind of liberation moment for Jews, to speculate,” Cohen, the musicology professor, said. “This is something he engaged with throughout his life both with the Israel Philharmonic, Halil, the Jubilee Games.” (Bernstein wrote the Jubilee Games for the 50th anniversary of the Israel Philharmonic.)

Bernstein also saw a deep connection between the development of different musical traditions in Israel and the development of its democracy and national character, as he wrote in a 1949 essay.

After detailing warring factions of musical styles within Israel he concluded that it reflected the work of democracy in action. “This is as it should be,” he wrote. “It means that out of this struggle will come a true voice, speaking for the real people of a real society.”

Bernstein’s Judaism was as deeply a part of his life as his music was — and, indeed, as deeply a part of his music as the rest of his life. The examples are admittedly overwhelming, but if Maestro had simply explored a few, it could have truly introduced viewers to the Bernstein who so deeply touched the world.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO