For Israel, a predicament that would be familiar to the authors of Greek tragedy

As with Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, Israel confronts a story where no happy ending is possible

The Theatre of Bacchus in Athens. Photo by Getty Images

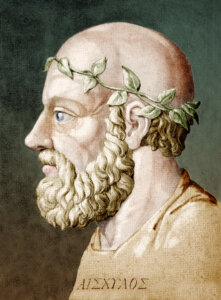

In 2018, a tragedy unfolded in Israel. Unusually, this one ended with rounds of applause, not ammunition. The curtain had fallen on the Gesher Theater’s production of Aeschylus’ great trilogy, the Oresteia. What struck many reviewers was how closely the political and moral issues facing the ancient Greeks resembled those confronting modern Israelis. “The bottom line,” declared one critic, “is that I definitely recommend watching the show, much of which is relevant to Israel.”

What a difference five years makes. What was merely relevant then seems to be terrifyingly contemporary today. Were Aeschylus alive today, he might well agree.

A dilemma where there are no good choices

Since its birth in 1948, Israel has been on intimate terms with tragedy. Perhaps never more so than today. Three weeks have passed since Hamas invaded several towns and kibbutzim near the Gazan border. They killed, often in appalling fashion, more than 1,400 people, including children. Since Hamas’ attack, health officials in Gaza report that more than 8,000 men, women, and children have been killed during the aerial and ground bombardments by the Israel Defense Forces.

These numbers, and what they represent, are impossible to grasp. And yet, impossibly, there is another number that competes for the world’s attention of Hamas and Israelis: the 200 or so hostages held by Hamas somewhere in its vast subterranean network of tunnels. (Always difficult to ascertain, the actual number of hostages has become even more uncertain given claims by Hamas that Israeli rockets and shells have killed several dozen of the hostages.)

The hostage situation is perhaps the single most important factor influencing the decisions now being made by both Hamas and Israel. Not surprisingly, many observers have used the word “dilemma” to describe the choices that have confronted Israel since the massacre. The terms of this dilemma are stark. On the one horn of this dilemma, Israel can accept Hamas’ demands to save the lives of the hostages. (These terms would be a magnitude greater than those agreed by Israel in 2011 for the release of a single soldier, Gilad Shalit.)

On the other horn, Israel can instead pursue its goal of destroying Hamas by a ground assault on its strongholds in Gaza. At the same time, the IDF will insist on a second goal of the attack: the liberation of the hostages. This is a claim, though, that many hostage families reject, instead insisting on negotiations. Their reasons are clear. If, as military analysts warn, the assault on Gaza will lead to months of urban battle and bloodshed, that will inevitably include the blood of the hostages on the hands of Hamas.

As military and intelligence experts predict, “there is no happy ending to this story.” This phrase also works as a definition of Greek tragedy. Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides did not do happy endings. Instead, they did endings that are horrifying. Horrifying not because they abound in human gore and guts — all of that took place off stage — but because they abound in human dilemmas. Dilemmas in which not only is there no good choice, but even the best bad choices are soul-battering.

Take the Agamemnon, the first play of the Oresteia. Commanded by the gods to lead an invasion on Troy after the Trojans steal away with Helen, Agamemnon finds himself listless. Literally. With no wind, his ships are stuck in the port of Aulis, unable to obey the gods’ command. When the fleet’s priest glimpses two eagles tear open and devour a pregnant hare, he concludes that Artemis, goddess of the unborn, has offered Agamemnon a deal he cannot refuse. To compensate for the carnage that he and his men will wreak in Troy, Agamemnon must in return sacrifice his own daughter Iphigenia.

There is no happy ending to this story. Confronted by this choice, Agamemnon cries out (in Robert Fagles’ translation):

Obey, obey, or a heavy doom will crush me!

Oh but doom will crush me

once I rend my child,

the glory of my house—

a father’s hands are stained,

blood of a young girl streaks the altar.

Pain both ways and what is worse?

Here is the heart of Greek tragedy: a collision between equally powerful and equally righteous imperatives. Something must give, but whatever that something is, the consequences will be terrible. There is no way out, but does that mean there is nothing to be done? If we listen to the chorus, we can perhaps learn lessons. Or, rather, just one lesson in this case — namely, that “we must suffer, suffer into truth.”

The only solution when there is no way out

In her brilliant study of ethics and Greek tragedy, The Fragility of Goodness, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum elaborates on the claim made by the chorus. While there is no practical solution to the dilemma posed in the Agamemnon, the truth of the matter is perhaps that we should not be looking for such solutions. The only solution, or truth, is the recognition that we must “describe and see the conflict clearly and to acknowledge that there is no way out.”

In turn, this means speaking clearly. Agamemnon fails to do so, with horrendous consequences. Once he “slips his neck in the strap of Fate” by choosing to sacrifice his daughter, Agamemnon stops referring to her as his daughter — or, indeed, as a human being. Instead, he calls her a “yearling,” fit only to be “hoisted on the altar.” What follows is too frightful for the chorus to describe, but necessary to recall when political leaders in Israel refer to Palestinians as “human animals.”

Though based on a myth, the Agamemnon has lessons to offer. (And Aeschylus has personal lessons to offer as well: He wished to be remembered not for the plays he wrote, but for the life he lived as an Athenian citizen who fought in the battles of Marathon and Salamis.) As the IDF continues its ground incursion into northern Gaza, it appears that Israel’s political and military leaders have made their choice concerning the hostages. Put simply, this is a choice that involves the sacrifice of not one, but many, innocent lives. It is, of course, a choice dictated by the harrowing situation created by Hamas. But it is also a choice about which Israel’s political leaders should speak clearly and candidly. Tragically, though, no one expects this government to rise to this Aeschylean imperative.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO