A very untraditional bat mitzvah tallit holds the key to tradition

For her daughter’s bat mitzvah, artist Mindy Stricke wove a symbolic web of tradition and ancestry

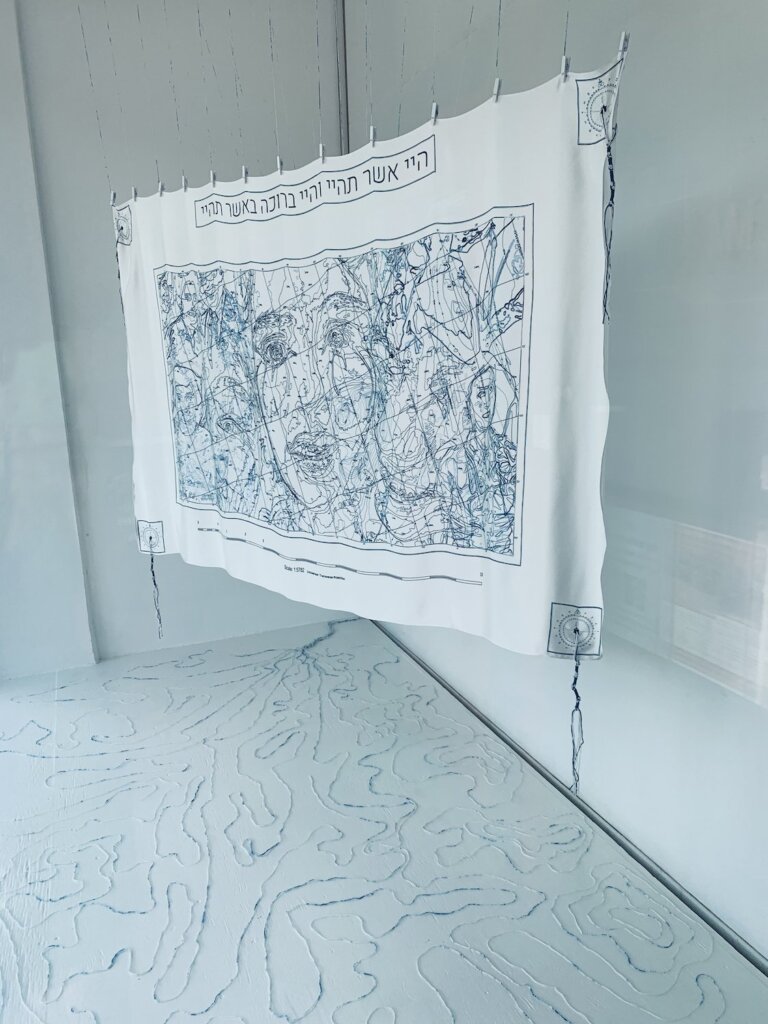

The tallit, installed in Fentster’s window, creates another map with the fringes dangling onto the floor. Photo by Morris Lum

As Jews, we celebrate adulthood at age 12 or 13. And while that may have once felt like adulthood, in the modern world, tweens are not considered grown-ups. Instead, b’nai mitzvah mark the beginning of an often-confusing time of self-discovery, the time when we begin to forge the person we will grow up to be.

As a parent, artist Mindy Stricke found herself grappling with how to support Noa, her oldest child, as she prepared for her ceremony. As a mother, she wanted to guide her daughter, but also knew the importance of letting the ceremony truly be Noa’s.

“My daughter becoming bat mitzvah meant sitting in that uncomfortable uncertainty of watching her grow,” said artist Mindy Stricke. “What happens when we let go and trust our teens to be who they are?”

The process of helping her daughter prepare for her bat mitzvah led Stricke to create her artpiece Fringes, currently installed at Fentster, an innovative Jewish art gallery based out of a storefront window in downtown Toronto. Eventually, when it comes down, Noa — who advised her mother throughout the process of creating the piece — will wear it.

Jewish teens are traditionally gifted a tallit (ritual prayer shawl) during their b’nai mitzvah. Often, those tallitot are the traditional blue and white, though sometimes they are tailored to the honoree’s preferences — rainbow striped or embroidered with plants, animals or Hebrew script.

But Stricke’s tallit is customized far beyond that; All the people and things that have, up to this point, formed Noa into who she is are referenced in the tallit. Fringes depicts Noa’s face within a topographical map of Montreal, where she became a bat mitzvah, surrounded by symbolic details: the blessing her parents recite over her each Friday night, her ancestors — themselves built out of topographical lines — and the initials of all those who attended her ceremony, placing Noa in the middle of a complicated web of ancestry and community.

Family members at their own b’nai mitzvah chant and dance from within the topography all around Noa’s face: Her father gazes from the top left, her mother — the artist — on the top right, with more family all around. The figures are abstract, their outlines hard to make out within the wavering lines of the topographical map. Yet they’re ever-present, an inalienable part of Noa’s unique self.

There’s something fundamentally awkward about b’nai mitzvah; after all, we take children in their most gawky, transitional state, when they’re just beginning to think about who they are and what they like, and have them stand and speak in public. But, Stricke said, this is also the point: At this vulnerable moment of becoming, the community is there to support and guide them.

“You carve your own path within that map, and that holds you when you go off the map,” she said. “You give the framework, but you don’t tell them what to do. It’s like a garden — you’re watering and each seed is going to come up totally differently and that’s ok. We don’t want a monoculture.”

Fittingly, the tallit is just as much about Stricke as it is about Noa — after all, they have shaped each other. Stricke’s philosophy of parenting and her Judaism mirror each other, both grappling with the tension between giving guidance and allowing freedom.

In Fringes, Stricke has come down strongly on the side of independence. Compasses adorn each corner of the tallit, a testament to Stricke’s belief that it is through exploring and getting lost that we can find home. For Stricke, it was through accepting herself as neurodivergent and queer that she found that she could create and accept her own Judaism, and the tallis is a gift of that same acceptance to her daughter.

“There’s no edge of the world. The fringe of one ecosystem leads into another one,” Stricke said. “It really hit me on the high holidays, this incredible framework and birthright I’ve been given that’s survived for thousands of years. To me, it has to be about that balance of rigidity and flexibility and willingness to be outside and stand on the fringes.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO