Her family escaped from pogroms to South Dakota — did they become complicit in the decimation of Native Americans?

Rebecca Clarren’s ‘The Cost of Free Land’ is a confession of collective guilt

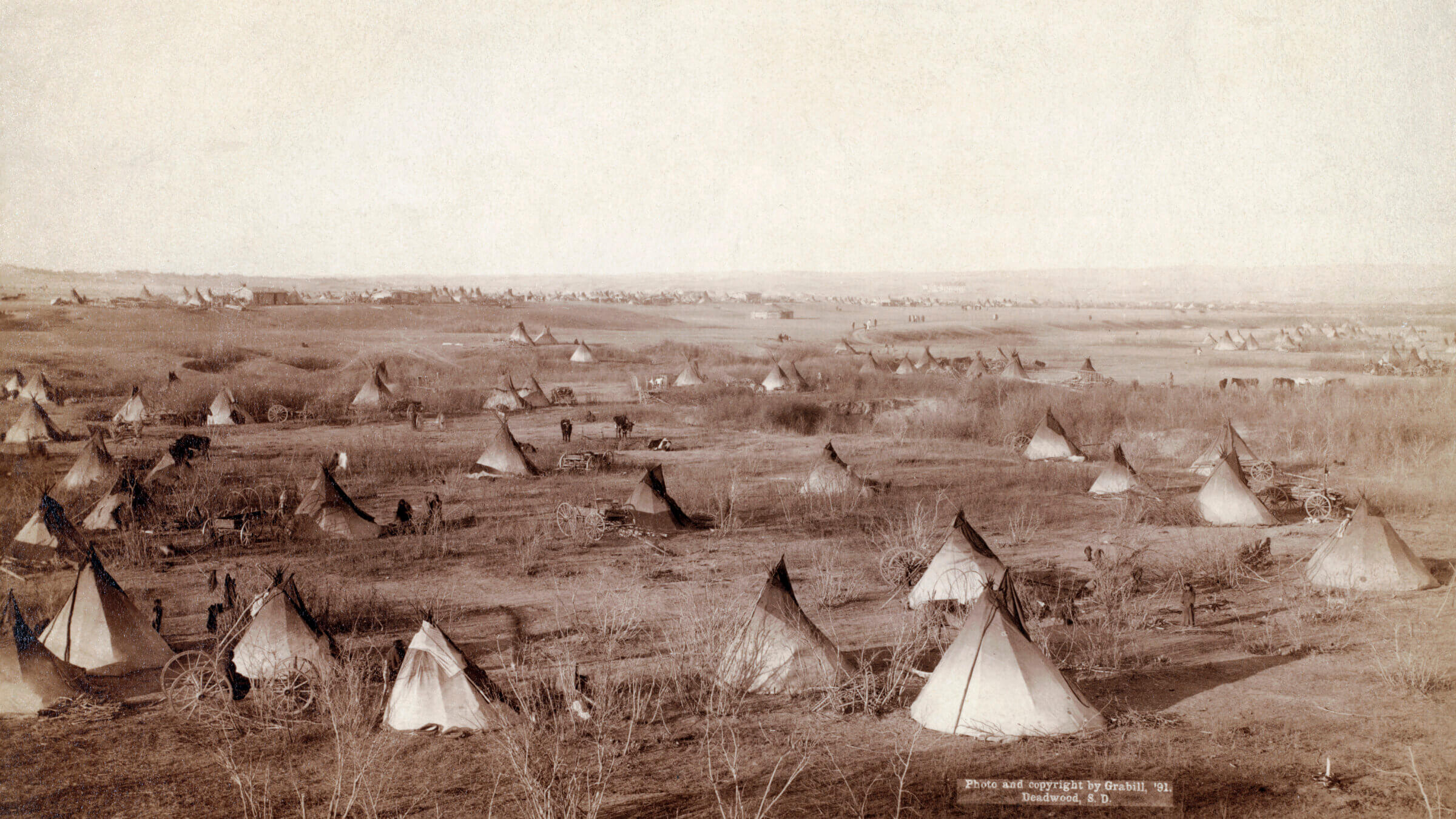

A Lakota tribal village in South Dakota, circa 1891. Photo by Getty Images

The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance

By Rebecca Clarren

Viking, 352 pages, $32

In 1895, Rebecca Clarren’s great-great-grandfather, Harry Sinykin, after barely surviving a pogrom in Odesa, immigrated to the United States. He ended up as a homesteader in South Dakota, with an allotment of free land to farm. His family eventually joined him there, with other Jewish settlers, in an area that became known as Jew Flats.

Accepting that land was, to Rebecca Clarren, her family’s original sin.

Her ancestors lived near the heart of Indian Country, where the Lakota people had endured massacres, broken treaties and outright theft. Federal policy had all but exterminated the buffalo, deprived the Lakota of their land and other resources, imperiled their cultural heritage and impoverished their reservations.

Clarren’s family were not major players in that centuries-long tragedy, only its beneficiaries. The author, though generations removed from the worst of the U.S. government’s double-dealing and her ancestors’ relative good fortune, is nevertheless wracked by guilt. Immersed in the study of atonement with a rabbi, she wants to make amends, and to inspire readers of The Cost of Free Land to do the same.

Her entire book, she writes, “can be read as a land acknowledgment to the Lakota Nation” — an extended version of the formulaic prologue to so many contemporary public events. Clarren is in tune with our larger, charged cultural conversation about systemic racism, white guilt and reparations, and The Cost of Free Land will resonate most with those already inclined to share her views.

Clarren is surely justified in urging the teaching of American history “in its full and nuanced complexity.” But her repetitive insistence on bearing history’s burden can seem unduly self-flagellating. “I know I sound like a broken record,” she concedes, “but frankly the record is broken.”

Though she is an elegant writer and serious reporter, Clarren’s collective guilt argument seems labored. The Cost of Free Land would have been more powerful if she were, for instance, a descendant of U.S. Sen. Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, whose 1887 land allotment law split tribal lands into small private plots that were often sold to non-Natives.

Or if she were related to the bureaucrats overseeing the brutal boarding schools where Native American children were confined and punished for speaking their language or practicing Native customs. Or to the perpetrators of any of the forced assimilation and land-grab policies that decimated the Lakota, and other Native Americans, and which many of us today rightly deplore.

But who exactly should shoulder the guilt, and to what end?

Clarren’s relatives, apart from living on land stolen by others, seem to have done nothing in particular to hurt the Lakota. And they faced hurdles of their own: the region’s harsh climate and unforgiving soil, antisemitism, legal fallout from ill-fated Prohibition-era bootlegging. One of Clarren’s great-uncles, Louie, suffered a broken back when a gangster pushed him down an elevator shaft, and financial ruin after a failed oil drilling scheme.

The Cost of Free Land serves as a vehicle for intertwining two distinct, occasionally intersecting, tales: of Jewish settlement in the West, and this country’s recurrent crimes against the Lakota. Clarren comes to realize that “the pride I take in my ancestors’ endurance” had kept her ignorant of “the systemic benefits that the federal government extended to us because we weren’t Indigenous but white, at least white enough.”

Any chronicle of U.S. treatment of Native Americans, though broadly familiar, retains its power to shock — all the more so when Clarren underlines its connections to Hitler’s racial ideology and policies. Depriving Native populations of citizenship and voting rights was one inspiration, Clarren writes, for Hitler’s downgrading of Jews to what she calls “second-class citizens” (though the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, to which Clarren refers, stripped German Jews of citizenship entirely).

Native reservations, Clarren writes, influenced the creation of Nazi concentration camps. And America’s westward expansion “served as Hitler’s template for what he called Lebensraum, living space,” which he used to justify invasion and mass murder. One chapter of The Cost of Free Land is titled “The Holocaust at Home.”

Clarren’s pack-rat relatives shared a rich and revelatory archive with her. (A genealogical chart would have been helpful, especially since she periodically refers to great-uncles as uncles.) Traumatized by a vicious beating during the pogrom, Harry was violent towards his wife, Faige Etke. One of their six children, Jack, was convicted and imprisoned for his bootlegging activities. Clarren’s great-aunt Etta viewed that chapter of family history as a shanda, or shame, and urged Clarren not to mention it. But an adviser told her that keeping secrets would deprive her of “the opportunity to take responsibility and share the fault.”

Clarren’s most eloquent passages describe her interactions with Doug White Bull, a relative of Sitting Bull, leader of the 19th-century Lakota resistance. Doug’s grandfather Joseph White Bull was Sitting Bull’s nephew and fought at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. According to one disputed account, Joseph killed the U.S. troop commander, George Armstrong Custer.

Clarren’s family archive includes an unsmiling photo of her great-uncle Jack facing Joseph White Bull, an image that she writes “creates more questions than it answers.” At one point, the author accompanies Doug White Bull to the cemetery where his grandfather is buried. When they finally find the gravesite, he kneels and addresses Joseph White Bull in Lakota. She respectfully steps away. It’s a singularly moving moment, embodying Clarren’s observation “that the past is threaded to today like string through a seam.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO