A high-tech answer to the dilemma of how to teach the Holocaust to kids without traumatizing them

“Courage to Act” at the Museum of Jewish Heritage uses hologram-like videos to recount the escape of 95% of Danish Jews to neutral Sweden

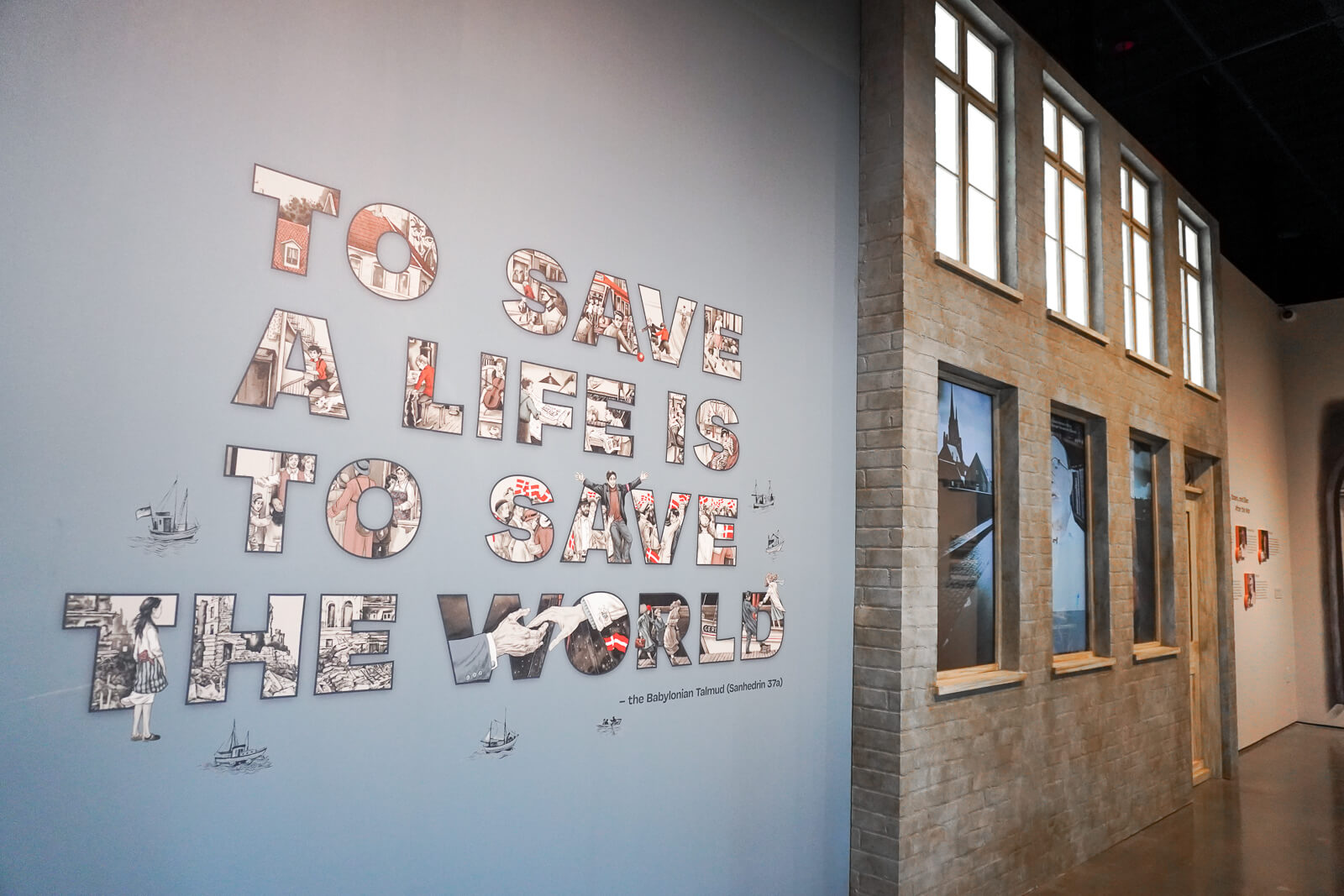

“Courage to Act” finishes with the saying, “to save a life is to save the world” from the Babylonian Talmud. Courtesy of Local Projects

“So you decided to help. Great. So listen: Talk is cheap, but it’s also dangerous. Don’t tell your parents what you’re up to.”

The speaker is a teenage boy in a plaid shirt and suspenders, standing behind a door frame, beckoning passersby to join in his plot to sabotage German soldiers. His name is Erik, and he’s a 14-year old Danish youth with a rebellious streak.

A video of Erik played for me when I pressed on a doorbell in the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s new high-tech exhibit, Courage to Act: Rescue in Denmark, which recounts the escape of 95% of the country’s Jews to safety in Sweden during Nazi occupation. The exhibit, recommended for children aged 9 and up, is part of the museum’s attempt to make Holocaust education understandable and meaningful — but not emotionally damaging — for kids in elementary school.

Staff at the Museum of Jewish Heritage (MJH), a New York-based museum that calls itself “a living memorial to the Holocaust,” said this is an important intervention in New York State, where public school students are not required to learn about the Holocaust until eighth grade.

“We should start Holocaust education — which is really human rights education — much earlier than middle school or high school,” said Regina Skyer, the museum’s Vice Chair. Skyer noted that children begin developing their own moral compasses around age 9, according to some psychologists. But there are concerns about exposing young children to material as potentially traumatizing as the Holocaust.

To figure out how to effectively reach young children, the museum assembled a team of advisors that included psychologists, teachers and principals as well as young adult historical fiction writer Steve Sheinkin.

The exhibit starts in 1942 Denmark, two years into a Nazi occupation that at first allowed Jews to continue living freely alongside non-Jewish Danes. It then recounts the leak of news that Danish Jews would soon be deported to concentration camps, followed by Danes’ exceptional response: smuggling more than 7000 Jews to Sweden via boat in the dead of night.

The exhibit is dotted with appearances by three fictional characters, played by child actors and brought to life as “Pepper’s Ghosts,” optical illusions created by projecting images onto sheets of glass. The characters speak with American accents in an intimate, sometimes conspiratorial tone. At the beginning of the exhibit, Rebekka, a 16-year-old Jewish refugee from Czechoslovakia who hasn’t heard from her parents in a long time, turns to the audience and asks, “Can I ask you something? Can you tell I’m not from here?”

Max, a 10-year-old Jewish Dane, sits on a box while his mother chats with vendors, and talks idly about a new classmate at his Jewish school who recently immigrated from Austria: “There, Germans just close the soccer field wherever they want, just because they’re Jewish. That could never happen here, right?”

The projections are the work of Local Projects, a design studio that helped turn Holocaust survivors’ testimonies into interactive videos at the Sydney Jewish Museum. The studio believes that these images are crucial bridges for children who are less and less likely to meet an actual Holocaust survivor.

“Resonating with this history in a more personal, more emotional level, will become much more challenging,” said Caroline Blockus of Local Projects. Each of the characters’ stories derive from a combination of at least five real narratives gathered from archives at places including the USC Shoah Foundation and the Danish Jewish Museum.

If this were an exhibit set exclusively in a concentration camp, introducing 9 year-olds to characters this lifelike might do emotional harm. But the story of a relatively successful maritime rescue provides safer grounds for empathy. Ellen Bari, the curator of the project, said that this unique narrative was “an opportunity for us to share something positive and still be sharing a story from the Holocaust.”

Bari and her team tried to avoid terrifying children in the section that relives the boat rescue — a dimly-lit room in which visitors sit on benches, listen to quotes recounting voyages to Sweden and look at a a replica of the Gerda III, a boat that ferried around 300 Jews to Sweden. The team did not allow kids to crawl into the hull, where the Jewish refugees hid, in part because they did not “want to scare kids,” Bari said.

And while the section on Theresienstadt, the concentration camp to which around 470 Danish Jews were deported, is grim, it avoids any graphic images. In telling the story of Danish Holocaust survivor Steen Metz, who played soccer with Czech children he befriended at the camp, the museum writes that he “was sad when his new friends stopped showing up for the game. Years later, Steen learned that all of those children had been sent to a death camp.”

The exhibit ends in a brightly-lit space with videos of grown adults recounting their experiences with the rescue. It’s an ending tempered by sadness: Visitors catch up with young Rebekka at a dining table cluttered with dishes, in a Swedish house where she works as a nanny. She has stopped writing letters to her parents, who still have not responded, and says, “I just pray they’re safe, and I try to focus on the day-to-day.” She’s studying to be a nurse, knowing that medical workers will be necessary “in the land of Israel.”

Rebekka’s bittersweet narrative was personal to Imogen Williams, the 18-year-old actress who played her. Williams’ late grandfather was a Danish Jewish man who fled Denmark for Sweden at age 15. “I didn’t know in detail what my grandfather went through when I was little,” she said, and acting as Rebekka helped her fill in the gaps. Rebekka’s story showed her that even during a time as difficult as the Holocaust, there were traces of hope, she said.

Indeed, Jenny Wong, a design director at Local Projects, said that the team tried to present examples of people who made a difference against seemingly overwhelming odds, in ways big — the 20-year old non-Jewish Danish woman who sailed the Gerda III across the Baltic sea with Jewish refugees hidden in its hull — and small, such as the Danes who sent care packages that helped keep Jews alive in Theresienstadt.

“There are many ways to help,” Wong said. “We want kids to feel that even though they’re small, they can still do something.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO