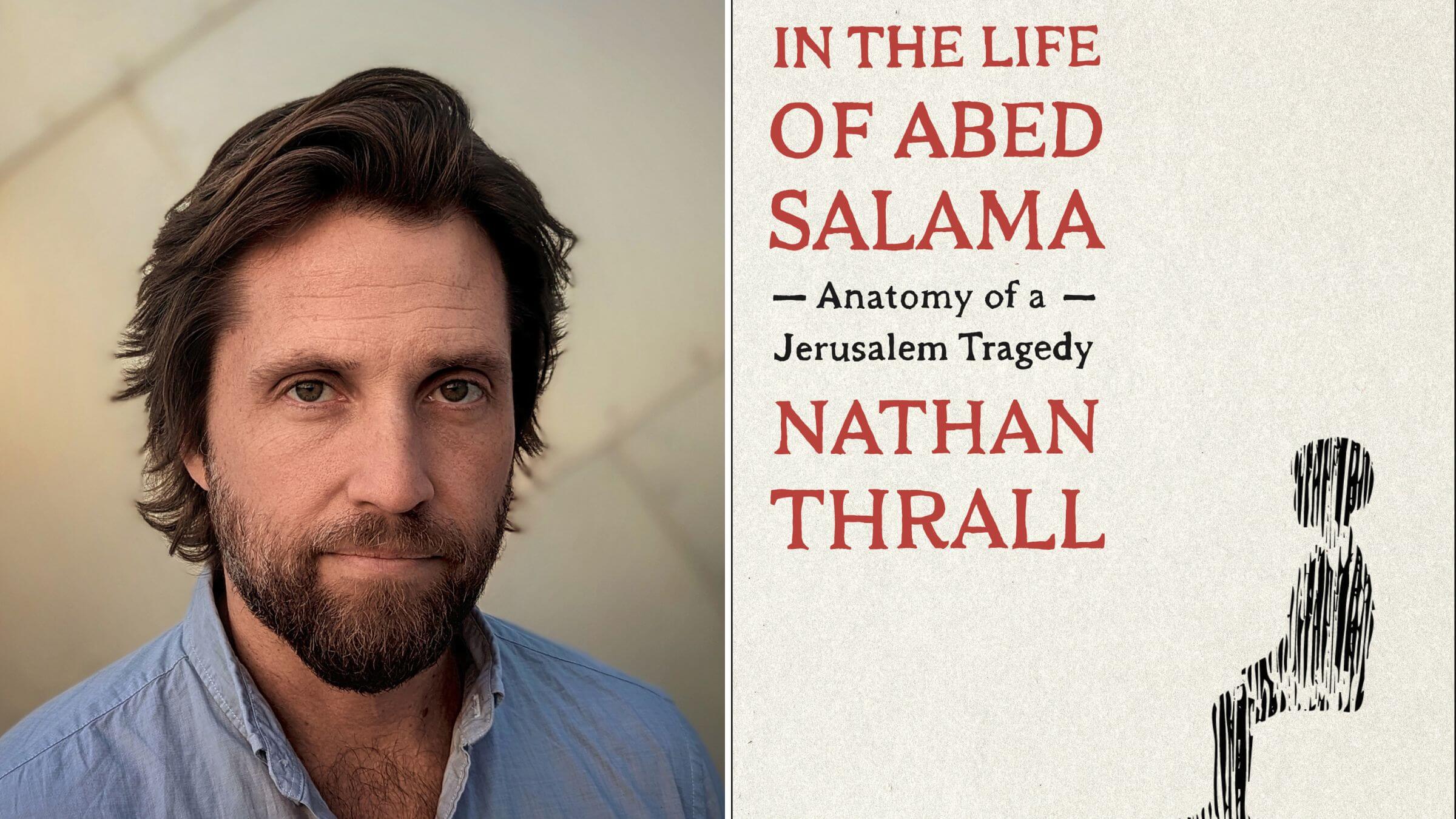

He wanted to tell the story of ordinary Palestinians living under occupation — will anyone want to listen now?

Nathan Thrall’s ‘A Day in the Life of Abed Salama’ is an intimately reported account of the aftermath of a lethal West Bank bus crash

Photo by Judy Heiblum

Editor’s note: Nathan Thrall was awarded the 2023 Pulitzer Prize in general non-fiction for A Day in the Life of Abed Salama on May 6, 2024.

When news broke of Hamas’ attacks on southern Israel, Nathan Thrall and Abed Salama were just beginning a book tour in New York City. Thrall, a think-tank researcher and writer who is originally from California, worried for his wife and daughters in Jerusalem. Salama, a lifelong Palestinian resident of a village in the occupied West Bank, received word that the Israeli army had closed the town’s exits and feared that his own family was trapped.

They had come to the United States to launch Thrall’s second book, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama, an intimately reported account of life in the West Bank. The book starts on a rainy 2012 morning, when a school bus crash on a highway outside Jerusalem killed six Palestinian children and one teacher. One of the victims was Salama’s 5-year-old son, Milad. The book follows Salama on a day-long search for his son. At the same time, Thrall attempts to tell the “entire story” of the occupation through extensive and intimate biographies of Salama and other parents, doctors and emergency workers who witnessed and responded to the crash.

Thrall, who worked for years as an analyst for the International Crisis Group, has a long and nuanced view of Israeli and Palestinian history that is now more relevant than he could have anticipated. After Hamas militants killed 1,200 Israelis and kidnapped at least 150, Israel has retaliated with airstrikes that have killed more than 1,000 people inside Gaza, a blockaded enclave of some 2 million.

I spoke with Thrall by Zoom about reporting Salama’s story and publishing it during a new wave of violence. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you come to see this crash as a good starting point for a broader story about Israeli and Palestinian history?

I live in Jerusalem, and the parents and children who were involved in this accident also live in Jerusalem. They live on the other side of a 26-foot separation wall. I would drive past this walled enclave on a weekly basis. When this accident took place, and I learned about how late the emergency response was, I couldn’t stop thinking about the entire community that shares this city with me but lives a radically different existence of total neglect.

I also felt that I could tell the entire story of Israel-Palestine in a microcosm. What you have here is the story of Jerusalem; of the annexation of East Jerusalem and two dozen surrounding villages; you have the permit system, in which some families have IDs that allow them to enter Jerusalem and some don’t; and you have the personal histories of the Jewish and Palestinian characters who intersected on the day of this accident.

As much as this book is about Abed Salama, it’s supposed to encapsulate the everyday lives of Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank. Within those everyday lives is a great deal of brutality and dehumanization.

There are characters in the book who were celebrating online the burning to death of innocent kindergarteners. There’s an Israeli TV news presenter who decided to make a special about this because he was horrified by that level of dehumanization and what it meant for the future.

There’s a Palestinian doctor who comes upon the scene of the crash and recalls when the Israeli air force bombed the PLO headquarters in Tunis, where she was stationed at the time, and where she picked up body parts of administrators and secretaries. There’s the Israeli ZAKA workers who come to look for body parts on this burned-out bus; they themselves have seen so much trauma that is the result of brutalization. That is in everyone’s consciousness as they navigate everyday life.

The community of Anata, as described in this book, revolves around close-knit family networks created over generations. You’re an outsider to that world, but you convinced dozens of people to tell you intimate stories. How did you build trust?

I found Abed through a personal connection. I was already looking into the accident and trying to meet anyone involved. A family friend told me she had a distant relative who was a parent of one of the children who passed away; she put me in touch with a less distant relative, who then put me in touch with Abed. There was a cloud of silence around the accident in his family and in many other families, and he was yearning to talk about it. Over the next four years we spent a great deal of time together; it wasn’t just a matter of reporting, it was a matter of grieving.

There were people who didn’t want to talk to me, but I think that it also went in the other direction. This is a society in which people are very closely related to one another. They might have been more reluctant to tell an insider about dynamics within families, or the other stories that make up the book.

There’s already debate about how we should talk about the events of the past week. Some people want to focus on the plight of Palestinians in Gaza right now or occupation as the “root cause” of this attack, while others have suggested that to do so is to justify Hamas’ actions. What do you think?

It’s not hard to say unequivocally that the killing of civilians is a war crime and is morally reprehensible, as is the collective punishment of 2.1 million Gazans with the cutting of food, water, and electricity. It’s not complicated to say that and to also say that this issue did not begin on Saturday. It has been going on for decades, and will continue to go on for a very long time, so long as we continue to pay attention to it only when there is an eruption of violence.

Two weeks before this attack, the U.N. put out a report stating that since 2022, over 1,100 Palestinian Bedouin in the West Bank have been forcibly transferred. That is ethnic cleansing, and that’s the calm that people are always calling to return to. The hope of the book, without anticipating the horrors of Saturday, was to draw attention to that and say, that cannot be the thing we’re trying to preserve.

You and Abed have both expressed hope that A Day in the Life can have a political impact. Have your thoughts about what the book can accomplish changed in the past week?

I’ll be perfectly honest with you, I think that what happened on Saturday is going to make it tremendously more difficult for people to have any receptivity to hearing about the ordinary lives of Palestinians under occupation. The level of brutality we saw on Saturday is going to overwhelm exactly the kind of people I hoped to reach with the book.

How would you describe that audience you’re trying to reach?

I was trying to speak to Israelis and Palestinians, but also American Jews and folks who couldn’t even point to Israel on the map. The purpose of telling the story through narrative was to reach a broad audience that could access it as a piece of storytelling.

There are many tours of the occupied territories given by activist groups; they show congressmen Hebron, or have leading rabbis sit down with Palestinians and hear about what their lives are like. What I have heard from basically everyone who has gone on one of those tours is that their perception was radically altered. A very simple way of describing this book is showing a reader what he would see if he went to the West Bank.

And you feel that sort of reckoning is impossible right now?

I hope I’m wrong. It could be that there will be greater curiosity about the roots of this conflict, and this book will be seen as a way of understanding the everyday reality that continues to boil up into horrific violence. On day five after this massacre happened, I feel that the world is looking at what happened and equating Palestinians as a whole with what Hamas did.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO