Haunting, poignant, unsettling, riveting — images from the precarious lives of artists in a diverse Israeli city

The art in ‘Tales and Textiles’ at JCC Manhattan reflects divergent backgrounds and similar experiences

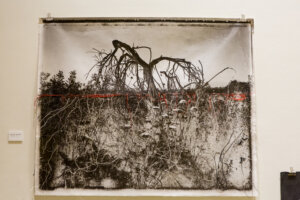

In Nahed Abo Alhega Hamza’s work, innocent and playful images are juxtaposed with sinister ones. Photo by Jennifer Weisbord

These are two of the more unsettling yet riveting exhibits that I’ve seen in recent years.

Tales and Textiles, presented by JCC Manhattan in collaboration with Israel’s Contemporary Arts Center Ramla, offers an amalgam of photography, painting and embroidery set on big backdrops — sweeping ceiling-to-floor canvases — and small ones — handkerchiefs, curtains and floor rags.

Rifts, Joints, and Rifts hangs on one side of the first floor gallery, representing the dual work of a Ukrainian Jewish couple, photographers Anna Hayat and Slava Pirksy. On the opposite wall, Palestinian artist Nahed Abo Alhega Hamza exhibits a collection of collages, paintings, and bits of memorabilia, titled Unheimliche, Longing, and the Floor Rag.

The three creators all reside in Ramla, an Israeli city known for its diversity.

Despite the differences in the artists’ backgrounds, overlapping themes emerge, most pointedly concepts of home, memory and loss. Rage and fear are evident too. But to call any of the pieces political is reductive. Mood and aesthetic juxtaposition are the artistic hallmarks throughout. Most significantly, the art on display recasts the most cloying of cliched images in a darker, if not ominous, light.

Take Hayat-Pirksy’s three-part photograph of a rose in a cylindrical vessel. The picture’s rectangular frame is broken. A sense of disconnection and dislocation are pervasive. It’s an unnerving piece on many fronts, starting with the single rose, which is “a charged image and suggests something romantic,” according to art critic and CACR chief curator Smadar Sheffi, who also curated this exhibit.

The vessel, Sheffi told me via Zoom, is in fact “the shell of a weapon that used to be very popular in Israeli homes, especially after the Six-Day War in 1967. The picture brings together romanticism and pain.”

In one of the more striking Hamza pieces, we see an embroidered image of children frolicking with their balloons at one end of the canvas. But alongside the happy colorful toddlers lurks a massive sinister face, rendered in black brush strokes and positioned slightly above a clenched fist. Inside the idyllic, an uninvited monster lies in wait.

An heir to Grosz and Beckmann

“I was fascinated by the intensity and strength in her work,” Sheffi said in reference to Hamza, whose work she first encountered in grad school. “It felt like an inner shout, but it was expressed on the most mundane textiles. Her work takes us to a dark place in ourselves, in our environment. Sort of like the show, Twin Peaks, a town that looks perfect with its manicured lawns, but that has little to do with what’s going on underneath.”

Hamza finds comfort, longing and sometimes terror in objects that symbolize childhood or, more usually, home, as literal place and metaphorical concept. The curtain from her girlhood room or a dust rag that her mother used may serve as her canvas. An item or scene that traditionally provides a sense of safety has been transformed into a place that, upon close examination, is not so friendly.

According to Sheffi, Hamza is an artistic heir of Georg Grosz and Max Beckmann, who were known for their distorted, deviant figures in a dark post-World War I Germany, just before the rise of Nazism. The German word in the exhibit’s title “Unheimliche,” means uncanny, creepy and eerie — and that says it all.

Asked if Hamza is addressing her experiences as a Palestinian living in Israel, Sheffi agrees that they are reflected in the work, but not in obvious ways. Hamza hints at the uprootedness of leaving places.

One of Hamza’s more evocative pieces is made up of three unironed embroidered handkerchiefs, souvenirs from her parents’ wedding. They’ve maintained their folds and creases. At first glance the piece seems nostalgic and sentimental. But looking at it for a few moments it could just as easily elicit, at least for this viewer, disappointment and failed dreams.

“The handkerchiefs were folded for 50 or 60 years and stored in boxes,” said Sheffi. “Nahed was born after that event. It’s a memory she can’t enter. But she puts architecture in the work that transcends time.”

In some strange way the handkerchiefs, and all that they conjure, becomes her memory too, and all the more poignant and haunting because Hamza’s mother recently died. “She is connected to her mother through the textiles,” Hamza said. “Sorting through the things left behind by deceased parents is an experience everyone can relate to.”

21st-century issues, 19th-century style

As far as Hayat and Pirksy’s photography is concerned, Sheffi has followed their work for more than a decade.

Hayat and Pirksy employ a large format view camera and Polaroid film, which Sheffi says conjures the look and feel of late-19th-century and early 20th-century photography.

“Their work also feels Eastern European and brings to mind the early masters of cinema, even as the subjects of their photographs are contemporary, including streets where they live right now, which is near the CACR. The work is sensuous and blurred, and at the same time a strong statement is present,” Sheffi told me.

“I find especially compelling the way they touch on themes of war and sorrow,” she continued. “They are both extremely upset with the war in Ukraine. In their work they explore pain in a particular historical moment, but not in cliched ways.”

Absent from their work are blue and yellow, colors identified with the Ukrainian flag that we’ve seen frequently as symbols of solidarity with the Ukrainian people.

Instead the duo have incorporated stitching into their work, particularly red stitching, which evokes blood and medical imagery and seems to comment on war everywhere, not just in Ukraine or Israel, as well as environmental concerns.

One piece features a destroyed, bent, barren and denuded tree above ground in an apocalyptic universe, while hidden beneath the topsoil, unusual life forms flourish. Their presence is a “secret,” Sheffi said, adding that Hayat and Pirksy’s art “sheds light on the unconscious.”

Sheffi is hopeful that the work on display will make viewers aware of their own layered environments and appreciate “just how precarious and vulnerable things are.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO