Can a Jewish philosopher held prisoner of war by the Nazis help explain the power of Trump’s mug shot?

Emmanuel Levinas’ ideas about the mystical meaning of faces lend new depth to the mug shot seen around the world

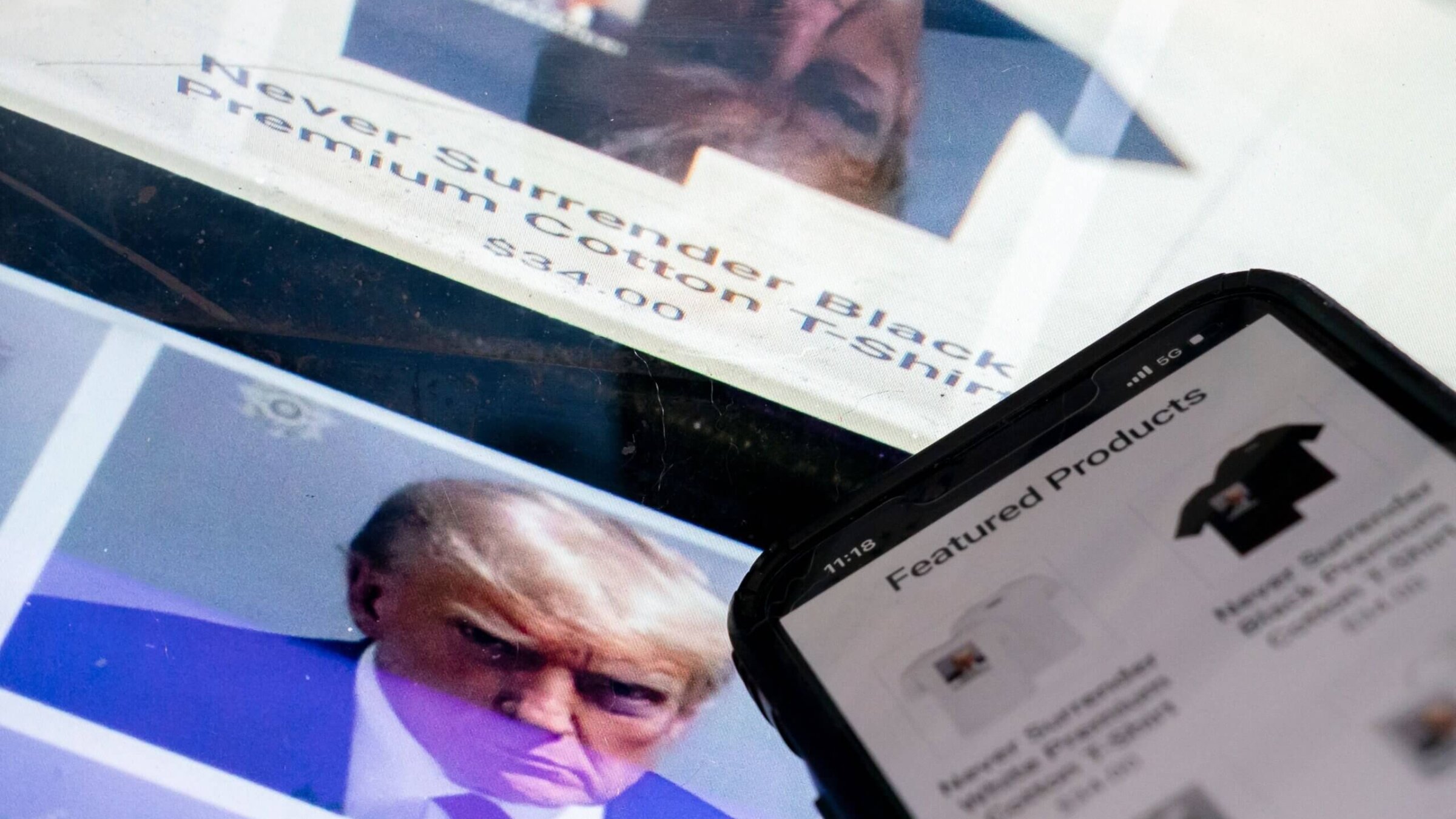

A photo illustration shows the mug shot of former U.S. President Donald Trump next to a website called Trump Save America JFC, a joint fundraising committee on behalf of Donald J. Trump for President 2024, which is selling merchandise bearing his mug shot. Photo by STEFANI REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images

“A Medusa reconfigured for the age of mass media.” “A weird mash-up of the 0.5 selfie aesthetic and Wanted: Dead or Alive classicism.” “A psychopath out of a Stanley Kubrick movie.” “A foolish old duffer with anger issues.”

Along with the succinct “thug,” these are a few of the critical responses sparked by the mug shot taken and released last week by a prison photographer of our once and perhaps future president. It seems Donald Trump’s face has launched a thousand quips.

But what if we were to drop the quips, and think about not just the meaning of Trump’s face in that mesmerizing mug shot, but the meaning of faces, period?

Many commentators seem to have responded to the mug shot by asking what Trump is trying to do with his face within it. The clear answer: He is trying to impress the viewer. Or, rather, impress upon the viewer a choice of messages: menace or mastery, the promise of revenge or resistance. (“Never surrender,” the motto Trump’s team plastered on newly released merch featuring the photo, was swiped from the Star Trek send-up “Galaxy Quest.” Poor Alan Rickman and the Thermians deserve better.)

But the more interesting question might be: How should we, the public confronting this unprecedented photo — the face of a former president, indicted on charges related to his alleged efforts to overturn the election — understand our own role in interpreting it? (And, yes, quipping about it.)

Perhaps no one has weighed in on the question of how to think about our reactions to other people’s faces more meaningfully than the French philosopher and theologian Emmanuel Levinas.

Born to an Orthodox Jewish family in Lithuania in 1906, Levinas moved to France in 1930 to pursue university studies; he fought for France and was interned as a prisoner of war during WWII. Upon his liberation in 1945, he returned to writing and teaching at a Jewish school in Paris. But he remained largely unknown until the early 1960s, when he published one of his major works, Totality and Infinity. It was only in the mid-1980s that Levinas was recognized as a maître à penser — a thinker whose thought is sought by others. In effect, he won fame at the same age as Trump won infamy.

Levinas’ thinking about the nature of faces is grounded in his belief that ethics is the first philosophy. Our task is to understand not the nature of reality or knowledge, but instead understand our duties toward others — a conviction he illustrated by citing a line from The Brothers Karamazov: “Each of us is responsible for everyone else, and I more than the others.”

Equally, Levinas believed that every human is fundamentally beyond knowing. In his philosophy, that is cause not for consternation, but celebration: Recognizing that other individuals are beyond our full comprehension helps us practice humility toward ourselves and humanity toward others. We care for others not because we are equal, but because we are not.

The face, for Levinas, is not the jumble of physical traits — nose, eyes, ears, mouth — we see in the mirror. Instead, the face radiates, Levinas declares, the naked and living presence of the other. Each and every face, utterly unique, is connected with every other face, Levinas posited in a turn to Jewish mysticism, because every face reveals the trace of God.

At this point, we see why Levinas was so drawn to Jewish mysticism. His understanding of the face combines the poetic and esoteric, urging us to remember the sanctity and sacredness of each and every one of us. When we come face-to-face with another, we are invited to remember that we are not alone.

And yet, Levinas would insist that our former president also has a face. Like many others, I thought I knew that face. When I first saw the mug shot, I was not surprised, but still was shocked.

“Really?” I asked my wife, Julie. “Should we laugh or cry?”

“Funny, but I’ve the impression he is trying not to cry,” Julie replied.

Looking again at the face, it was as if I have never really looked before at it. There is terror and torment in that face, but also, Levinas would claim, a trace of God. We must pursue justice, but we cannot forget our responsibility to others — yes, even those who sought to undermine our election.

This pursuit — of justice and humanity, even when they seem to conflict — is part and parcel of our sense of responsibility. And it’s that, truly, that we must never surrender.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO