How (and why) did a Bollywood movie make Auschwitz into a lesson on romance?

A new Indian movie takes a tour of the Holocaust sites for unusual reasons

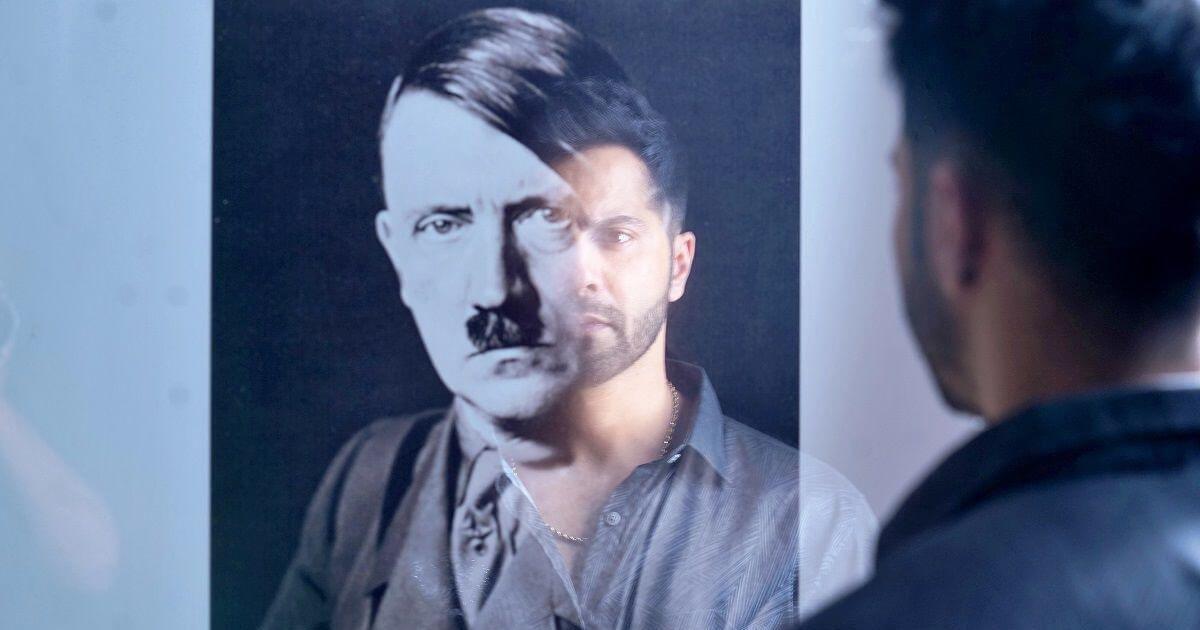

Ajay, played by Bollywood star Varun Dhawan, literally seeing himself in Hitler while at a Berlin museum. Courtesy of Bawaal

“Every relationship goes through their Auschwitz,” says the heroine of Bawaal, a new Bollywood film, released last week on Amazon Prime. A screenshot of the scene instantly went viral, but it’s far from the only disconcerting Holocaust moment during Bawaal’s two hour-plus runtime, leading the Simon Wiesenthal Center to release a statement condemning the movie and demanding that Amazon remove it from Prime Video, due to its “outlandish abuse of the Nazi Holocaust as a plot device.”

The plot device in question is a grand tour of the Holocaust’s greatest hits, each one of which enables the leading couple, Ajay, a self-centered schoolteacher, and Nisha, his long-suffering wife, gain perspective on their problems and save their troubled marriage.

The Eurotrip is a result of Ajay’s poor teaching; he’s almost fired when he can’t answer a student’s question about the Holocaust. In an attempt to save his job, he takes off to visit the sites in real life, with Nisha in tow. But he doesn’t learn history so much as life lessons.

I never understand why actors don’t say NO to such projects. Especially those like #VarunDhawan or #JahnviKapoor who can easily pick films they want to do.

— Somya Lakhani (@somyalakhani) July 21, 2023

Imagine, having a choice and picking THIS? ?#Bawaal pic.twitter.com/Bp2maW4PP0

A visit to Anne Frank’s house teaches Ajay to be less picky, because, as the guide explains, the Franks “didn’t have much but they were happy with whatever they had.” A museum on Hitler in Berlin teaches him to be less envious; “it’s because of his greed that half the world suffered a great loss,” Ajay says of Hitler, making the entirety of World War II sound like a personal foible. Auschwitz teaches about love and loss; the viral line is actually first spoken by a survivor, played by Richard Tate, who explains in a speech to tourists that he never really loved his wife until they were separated at the concentration camp.

This leads to perhaps the most insensitive scene in the entire movie, in which Ajay pictures himself in the gas chamber, reaching desperately for Nisha across a sea of naked Jewish men violently choking on Zyklon B. This imagined horror is the climax of the movie, allowing Ajay to realize that he loves his wife.

There’s also some subtle distortions and omissions in the movie’s presentation of history, even outside of Ajay’s imagination. Jews are only identified as the Nazis’ targets once, during the couple’s visit to Anne Frank’s house; otherwise, though the movie gives some statistics of how many people died, it doesn’t specify who was targeted or why. World War II is portrayed as the simple result of Hitler’s egoism. I would prefer, for example, not to believe that “we’re all a little like Hitler” just because “we aren’t satisfied with what we have,” as Nisha muses to Ajay while touring Berlin. I’m also pretty sure the reason there’s no memorial to the Fuhrer isn’t just because “an image created with the help of lies and propaganda doesn’t last for long,” as Ajay explains at another point, but instead because he murdered millions of people.

There are plenty of bad movies that fly under the radar, but though Bawaal was released directly to streaming platforms, it’s a big, high-budget effort, and comes from Bollywood heavy hitters such as director Nitesh Tiwari. This has led to staunch defenses of the film, especially from die-hard fans of the stars, Jahnvi Kapoor and Varun Dhawan. On Twitter, some viewers complimented the performances, and called the Holocaust concept creative. Others said that anyone who understood the Holocaust parallels as a marriage metaphor missed the point of the movie, arguing that Ajay reforms because he understands, and is moved by, the scale of the atrocities of the Holocaust, putting his own small problems into perspective. Thus, the argument goes, the movie is not offensive — it’s educational.

People might have different opinions on a film as it is subjective. But whoever is hating #Bawaal thinking that the film is equating the problems of a marriage to the horrors faced by the Jews during WW2 seems to have completely missed the point that the film is trying to make

— Sagar (@estudiodesagar) July 21, 2023

In an interview, Kapoor said that an Israeli acquaintance of hers saw the movie and enjoyed it, without finding it objectionable. “The intention has always been pure, and always to acknowledge the turmoil, the devastation and the monstrosity of what happened,” she said.

But to many viewers, the idea that the movie is meant to teach about the Holocaust feels patently false. What does it mean for intentions to be pure if no one thought harder about the way the movie’s plot minimizes the suffering of millions? Shouldn’t they have been more careful not to distort history?

Of course, a Bollywood romance is not meant to be educational. And, given the historical connections between Nazism and Hindu nationalism, as well as a worrying trend toward adoration of Hitler in India and Pakistan — a portion of the population of which consider themselves Aryan — it seems good that Ajay says flatly that “Hitler was a bad guy.”

We are so often told to learn from history. And Bollywood is far from the only place where the Holocaust is used as a sort of morality play. In the West, too, educators have, for decades, used the Holocaust to teach morality and empathy. Bawaal fits this mold well; through learning about the Holocaust, Ajay learns empathy for his wife, for his students and for his parents.

And while it’s bad that the movie glosses over and distorts history, it is far from the only piece of media to use the Holocaust as a plot device; most Holocaust movies and books are about more than just history. Think Life is Beautiful or The Fault in Our Stars or Sophie’s Choice. Bawaal feels in bad taste, but is that simply because Westerners find most Bollywood movies, with their musical numbers and dramatic love stories, cheesy? Would we find the same concept, told differently, more palatable, or even edgy?

It’s hard to say. But as we move farther away from the real events, I expect to see more and more convoluted morality plays about World War II, and attempts to make the Holocaust into something clear-cut and productive. After all, we are supposed to learn from the Holocaust. But it’s not particularly clear what we’re supposed to learn. Still, perhaps the Shoah’s main lesson probably shouldn’t be #RelationshipGoals.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO