Iran’s Jewish languages are dying. Can intrepid linguists save them before it’s too late?

The Jewish Language Project is racing the clock to preserve a rapidly disappearing heritage

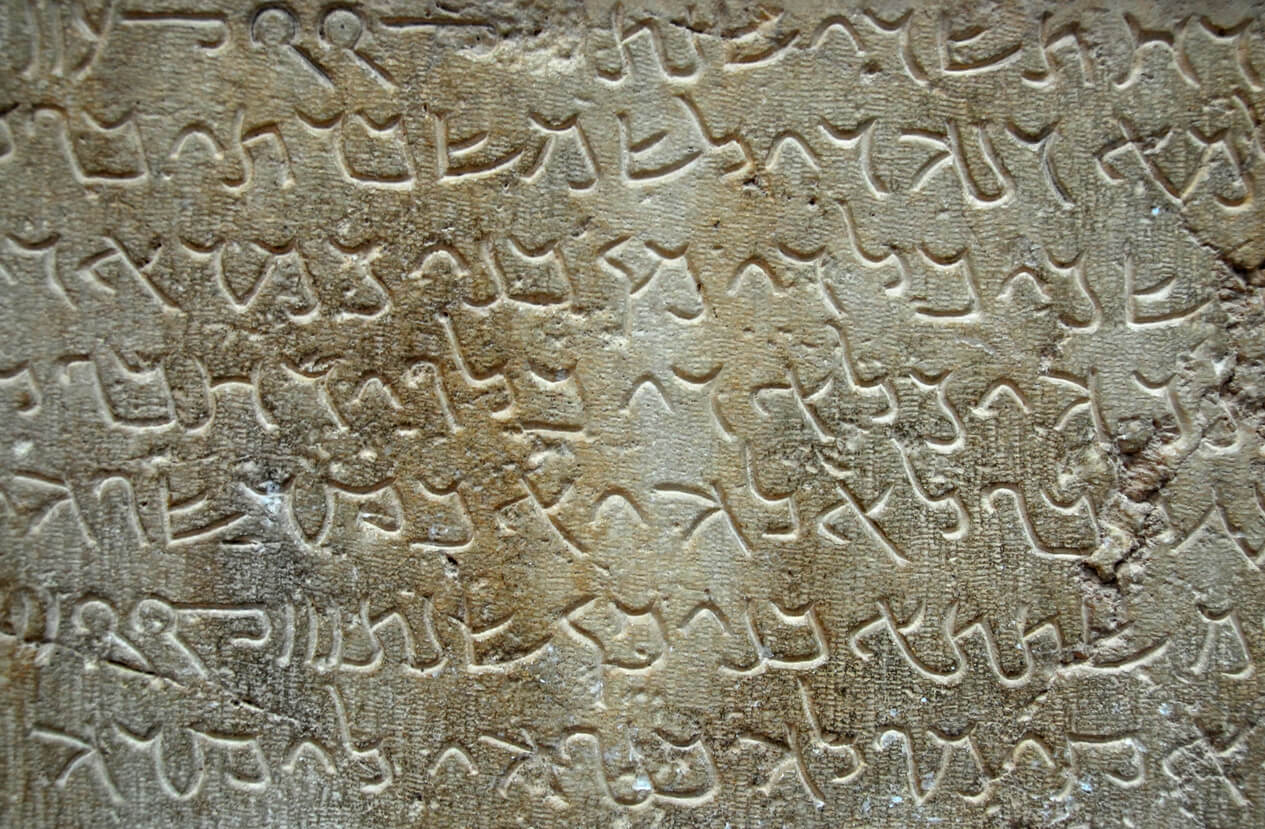

A stone slab with Aramaic inscription. Photo by iStock

For centuries in Iran, each Jewish community had its own language. Judeo-Iranian languages include Esfāhāni, Yazdi, Kermāni, Shīrāzi, Hamedāni, Kāshāni, Nehavandi, Borujerdi, Khunsāri and Golpāygān.

For the uninitiated, Esfāhāni is the language of Jews of Esfahan, and Shīrāzi is the language of Jews of Shiraz.

These are all non-Persian, Iranian languages historically spoken by Jews in what is the country of Iran today.

Most of these languages are currently extinct, or close to it. But soon, Wikipedia will help keep them alive. At the Jewish Language Project, an incredible initiative at The Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, a team is currently documenting these endangered languages, in collaboration with Wikitongues, a language revitalization organization. They’re creating videos with the remaining living speakers — and providing translations — before time runs out. [Editor’s note: The author of this piece serves on the board of the Jewish Language Project. She is not involved with the project on the Jewish languages of Iran in any way.]

With the support of a grant from the Wikimedia Foundation, Jacob Kodner, documentation manager at the Jewish Language Project, is leading a team to create new video content in six critically endangered Jewish languages and dialects. Kodner, who will begin a doctorate at Harvard University in linguistics in the fall, told me he plans to continue working with endangered languages.

“What really struck me throughout administering this grant is not only the diversity in languages we’ve been documenting, but also the diversity in experiences of the speakers we have been working with,” Kodner said.

Filming the last Neo-Aramaic-speaking Jews

In addition to the effort to document Judeo-Iranian, this project is also helping bring to light the fascinating world of Neo-Aramaic.

Many Jews in the Kurdish region spoke Jewish Neo-Aramaic, an extension of the ancient Aramaic language. It is typically divided into dialects such as Lishana Noshan (from the town of Tekab, Iran), Lishana Deni (from Zakho, Iraq), and Lishan Didan (Urmia, Iran). Today, many of those Jewish Neo-Aramaic speakers speak Hebrew.

Most Neo-Aramaic-speaking Jews made aliyah in the 1950s through the 1970s, and once in Israel, switched to Hebrew. In the early days of the state of Israel, there was a major effort to establish Hebrew as the primary language of the Jewish people. A variety of Jewish languages — for example, Yiddish and Neo-Aramaic — suffered.

Neo-Aramaic is now nearly extinct. According to estimates from the Jewish Language Project, just 500 elderly speakers of Neo-Aramaic are alive today. Most of them live in in Israel.

A team translation effort

The documentation initiative includes oral histories on video, along with translation and transcription. Some of these can already be viewed here and on YouTube.

After recording each video, the team transcribes and translates them for posterity. In addition, they hold edit-a-thons to edit the Wikipedia articles about each language and dialect (such as Judeo-Kāshāni, Judeo-Esfāhāni, Lishan Didan) and language group (Judeo-Iranian and Jewish Neo-Aramaic). There will be eight Wikipedia articles in all.

Time is of the essence in this project, as native speakers die out.

“As a result of migrations, genocide, assimilation, and language policies over the last two centuries, most longstanding Diaspora Jewish languages are currently endangered,” the grant proposal submitted to Wikimedia stated. “In the 2020s we have a unique, time-sensitive opportunity to research these languages. Some elderly speakers are still living, especially in the United States and Israel. It is imperative that we document and raise awareness about these languages in the next decade. For the sake of the elderly Jews who are their last speakers, for the sake of Jewish children who would benefit from knowing about their multifaceted heritage, and to build knowledge in general.”

Jewish Iran, Beyond Farsi and Hebrew

For the team working on this documentation, the project has often been personal.

“What’s most memorable for me,” said Alan Niku, a filmmaker, writer, and scholar of Mizrahi culture, “is that many of these languages are directly from my heritage, though they were lost over the generations as people moved to Tehran.”

“So I grew up speaking Farsi, and only later realized how many more languages my recent ancestors spoke.”

“Some of these communities are very small and connected too,” said Niku. “Virtually every speaker of Hulaula (Jewish Neo-Aramaic from Sanandaj) that I have spoken to or interviewed somehow knew my grandfather, who passed away when I was 3, and had some kind of story to tell about him.”

“His language has been lost from our family, but by learning it, I’ve been able to connect with a whole new family (Aramaic-speaking Jews) that I never really knew I had.”

For Kodner, one highlight was conducting a virtual interview with a speaker of Judeo-Shirazi. “The speaker shared that he received his Ph.D. in linguistics—the exact path I will be pursuing,” he said. “Hearing about his experiences as a linguist, such as his work on verb forms in Judeo-Shirazi, gave me a new perspective on the field I’ve entered and also the critical documentation work our organization is conducting.”

An international effort to record — fast

The documentation team is international, with some members interviewing relatives. Michael Zargari, who recently received his master’s degree from UC Santa Barbara, is currently working with his grandmother to transcribe an oral history in Judeo-Esfahani. Samuel Miller interviewed his grandmother for the video on Lishan Didan, the Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialect from Urmia, Iran.

Many members of the team are graduate or undergraduate students. For older linguists, it has been moving to see so many young people involved in this time-sensitive effort.

Still, it can be tough to procure funding for Jewish languages.

“The Jewish Language Project has been declined for grants from 11 Jewish foundations,” said Sarah Benor, who in addition to being a professor is the director of the Jewish Language Project. “Of course we’re competing against many worthy causes, but we’ve gotten feedback that our work is too niche or doesn’t address major issues in Jewish communal life. We’re so grateful that the Wikimedia Foundation recognizes the importance of documenting and raising awareness about endangered languages.”

Over 1.3 million people have visited the Jewish Language Project’s websites since the launch in 2020. JLP is on track to complete its documentation project in November 2023.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO