How Milan Kundera embodied the Jewish spirit

The author of ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Being’ praised Jews for keeping faith with cosmopolitanism

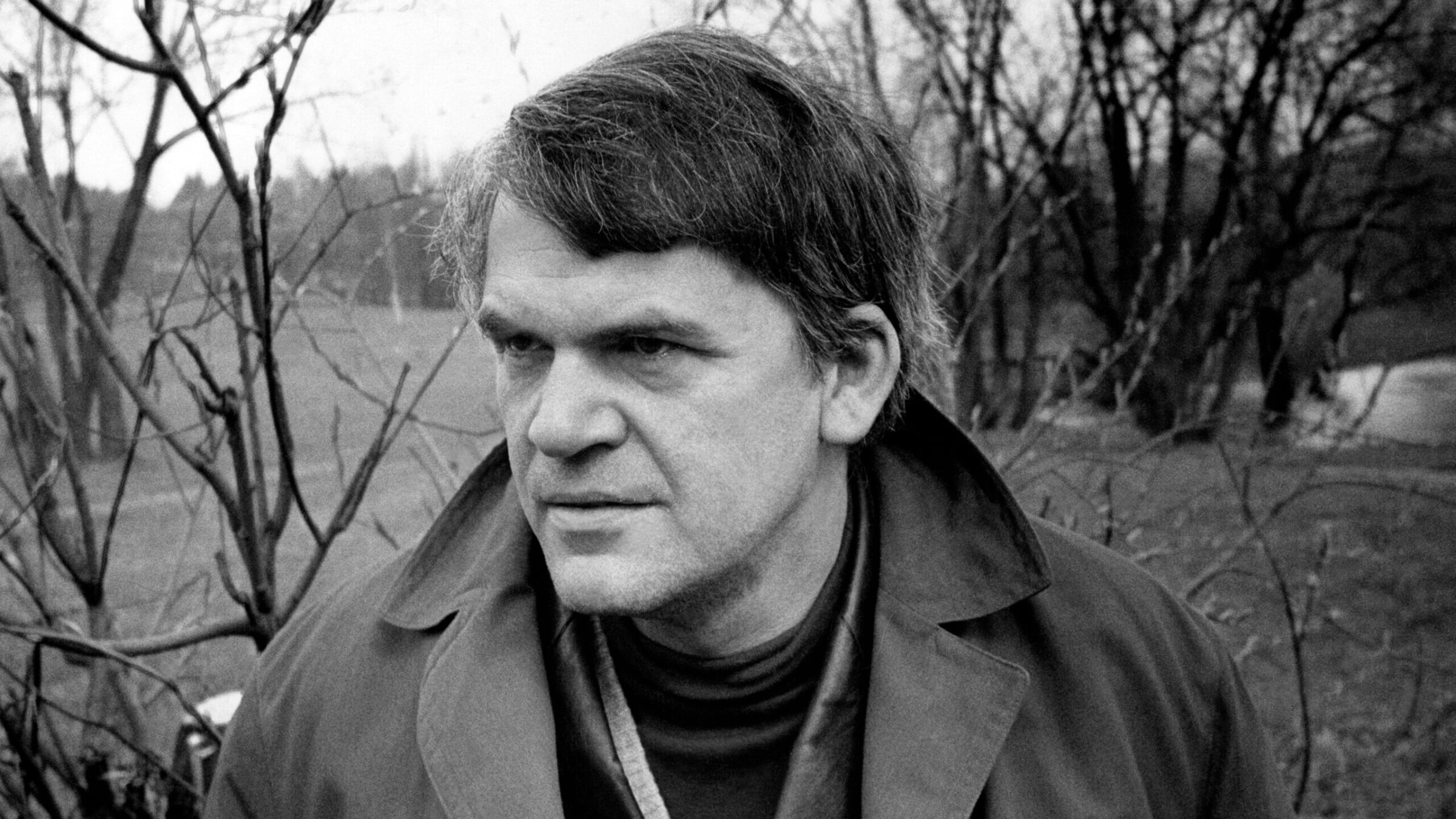

Milan Kundera poses in a garden in Prague, circa 1973. Photo by Getty Images

The novelist Milan Kundera, who died July 11 at age 94, revered Jewish culture, but as an ironist added a dark message of doom to his works: Just as central European Jewish culture was destroyed by the Nazis, so European culture in its entirety is mortal and may not survive in future.

In such novels as The Joke (1967), The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), Kundera was inspired by Jewish creative spirits listed in a 1984 essay, including Sigmund Freud, Edmund Husserl, Gustav Mahler, Franz Kafka, poets Julius Zeyer and Tibor Déry, and novelists Joseph Roth and Danilo Kiš.

Kundera underlined that central Europe was uniquely marked by the influence of Jewish genius. That was why, he added, he loved the Jewish heritage and clung to it “with as much passion and as though it were my own.”

Echoing these thoughts in a 1985 acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society, he again praised Jews for having kept faith with European cosmopolitanism. Kundera described the emotion that he felt on receiving the literary prize as emblematic of that great cosmopolitan Jewish spirit.

Repurposing a Soviet bloc antisemitic code word, implying that Jews as cosmopolitans were insufficiently patriotic, Kundera saw it as a positive virtue that Israel became a “little homeland finally regained” and represented “the true heart of Europe — a heart strangely located outside the body.”

Kundera also cited the Yiddish proverb “A man thinks and God laughs” (Der mentsh trakht un got lakht), which he paraphrased in a French equivalent of “Man thinks, God laughs,” about the uncertainty of planning.

Yet Kundera’s own literary achievement was surely the result of painstaking planning, even if the historical tragedy in Kundera’s homeland brought forth an ultimately dismal message of the triumph of human stupidity.

This was reinforced by early music lessons in Brno, Moravia, with the Czech Jewish composer Pavel Haas, who would be murdered in Auschwitz. Kundera’s first marriage was to Haas’ daughter, the Czech Jewish operetta singer Olga Haasová-Smrčková. Yet even Kundera’s love of music would be dampened by recollections of how his father, a noted musicologist, failed to launch a piano career because he insisted on playing such unpopular Jewish modernists as Arnold Schoenberg.

Decades later, in his 2000 novel Ignorance, Kundera wryly noted that in 1921, Schoenberg had declared that his work alone would guarantee that German music would continue to dominate the world for the next century. Observing that public interest in Schoenberg’s music had faded with time, Kundera explained that the composer “overestimated the future” because he dwelled in “too lofty spheres.”

Kundera’s own lofty admiration for Yiddishkeit could not stomach certain Jews, such as the Russian Jewish virtuoso Vladimir Horowitz, who reveled in glitzy works by Franz Liszt, the antithesis of the artistic rigor of the novelist’s father. In his book Art of the Novel, Kundera included “Horowitz at the piano” among things that he detested “profoundly and sincerely.”

Undiscerning audiences who rejected his father were to be expected in a world where, as Kundera told the Jerusalem audience, even major Jewish thinkers like Marx and Freud were outdone by modern stupidity, which he defined as the “nonthought of received ideas.”

And just as Kundera’s love for the Jews did not extend to Horowitz, so conversely did some Jewish readers not always kvell at his work.

Philip Roth was a fan and close friend, including two Kundera novels in the prestigious Writers from the Other Europe series he edited for Penguin Books. Prizing the liberating erotism in Roth’s novels, Kundera shared with his American friend the notion that fiction was not a domain for moralistic messages of any kind.

Yet Roth’s pal Saul Bellow was unconvinced, telling an interviewer in 1997 that Kundera was merely “a kind of dandy” as a “Eastern European who is crazy about France and Paris and the dernier cri.” Bellow conceded that Kundera’s writing achieved its goals more or less successfully, but added the caveat: “I don’t really take much interest in it.”

Nor was Pierre Assouline, a French journalist of Moroccan Jewish origin, thrilled by Kundera’s later works, written directly in a leaden French, as opposed to his soaring Czech-language fantasias of yore.

Assouline was nonplussed by the way Kundera reconstructed his past after arriving in France in 1975, doing everything to suppress his early Stalinist verse penned during membership in the Czech Communist Party. And Kundera vehemently, if unconvincingly, denied the assertion in a 2008 Czech biography that, as a 21-year-old university student, he had denounced a fellow student for expressing Western attitudes. That student was sentenced to 22 years of imprisonment, many of which were served in a labor camp.

Kundera also baffled Assouline by insisting in The Curtain, a seven-part essay, that Kafka was a “German writer,” as if clearing the way to Kundera’s preeminence as a Czech-language magician. And Kundera asserted in the same book that having witnessed the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Russia, he knew “what no Frenchman” could about experiencing the death of a homeland; Assouline drily inquired if Kundera had ever heard of France during the German occupation.

In addition to Kundera’s adoration of Jewish authors, he also cherished a few antisemites, such as Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Kundera so esteemed Céline’s novels that he willingly forfeited his own author royalties early in his career so that his Czech publishing house could also print works by Céline.

Kundera likewise lauded The Skin, by the Fascist Italian author Curzio Malaparte, an account of war atrocities, including Jews crucified on trees in Ukraine in 1941. Kundera always empathized with Jews, even minor characters, such as the student Sarah in his Book of Laughter and Forgetting, who like his narrator was experiencing a form of exile.

But a certain Janus-faced quality could make Kundera somewhat perplexing; scorning publicity and journalists, whom he termed “sniffer dogs” in 1984, Kundera nevertheless deigned to appear on the trendy French book chat TV show Apostrophes, where he was duly lionized. Ostensibly shunning the French literary world, he chose to live on the ultra-chic rue Récamier in Paris’ seventh arrondissement, where his favorite dining spot, crowded with publishers and editors, served frog’s legs seasoned with garlic and parsley, a dish he relished.

These apparent contradictions paled before Kundera’s latter-day dictatorial passion to remove himself entirely from any historical context (hardly an approach inspired by Judaism). Notoriously, the unsatisfying two-volume edition of his works published in the pricey Pléiade series by Les Éditions Gallimard lacked scholarly documentation, usually a trademark of this format.

And Kundera spent recent years destroying manuscripts, letters, and any other documentation that might testify to earlier life, whether pro-Stalinist missteps were involved or not. A peculiar hagiography has just appeared authored by a French biographer of Isaac Bashevis Singer, hampered by Kundera’s refusal to permit the writer access to people who knew him in earlier years.

Perhaps even more than the sympathetic image of Jews that he created in his writings, Kundera was ultimately obsessed by his own self-image.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO