Before Google, before Wikipedia, this DIY almanac shaped a Jewish generation

Even if you’ve never heard of ‘The Jewish Catalog,’ which turns 50 this year, it probably changed your life.

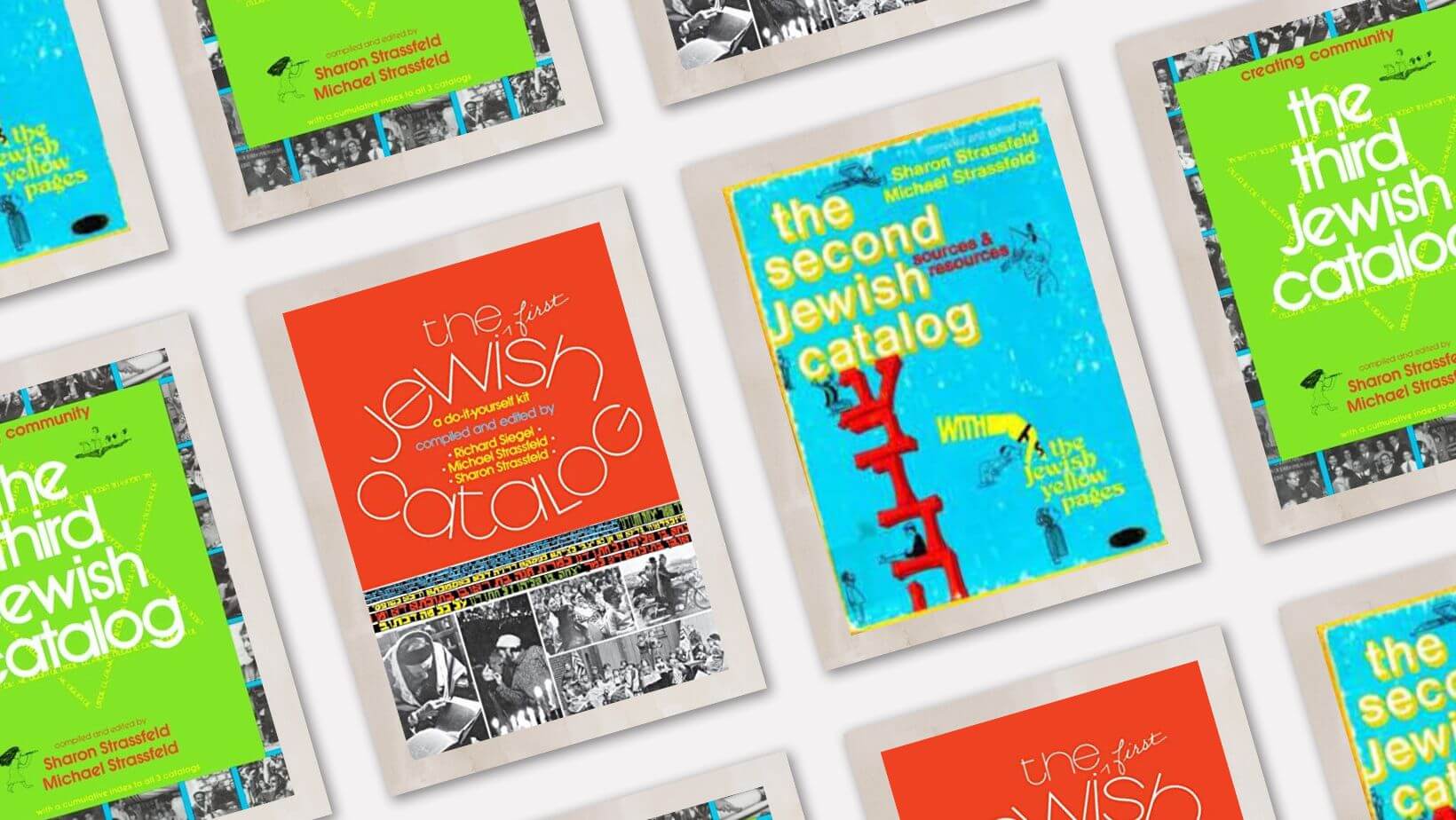

Courtesy of The Jewish Publication Society

Marcia Kern always planned to raise a Jewish family. But from the moment she became a mother in 1979, she had to depart from the traditional path she’d envisioned.

A 10-month pregnancy and unplanned Caesarean section to deliver her son left Kern mentally and emotionally exhausted. Eight days later, when a bris — the ritual circumcision prescribed by Jewish law — was supposed to take place, she couldn’t contemplate leaving her house, much less schmoozing at synagogue. Besides, bris ceremonies had always made her uncomfortable.

“I hated the fact that the men made stupid jokes and the women cried in the other room,” said Kern, now 72.

If Kern had given birth just a few years earlier, she might have pushed aside her reservations and dutifully arranged a conventional bris. Or she might have foregone the ritual altogether. But Kern started her family six years after the publication of The Jewish Catalog, a bestselling guide to DIY Judaism. A bris, the Catalog informed her, didn’t require a synagogue or even a rabbi. Anyone who could recite the necessary blessings, which were conveniently printed in the Catalog, was qualified to perform the ritual.

Armed with this knowledge, Kern’s husband set out for the hospital with two candles, a bottle of wine, and their newborn son. He officiated the ceremony, and a doctor performed the circumcision. Separated from her son for the first time, Kern admitted, she did cry a little. But the solution she and her husband had devised was exactly what she needed — and what, until the advent of the Catalog, she didn’t know she could have.

First published 50 years ago, The Jewish Catalog taught a generation of readers like Kern that they could live Jewishly without feeling beholden to unsatisfying or outdated customs. Created by three scrappy 20-somethings and infused with the relaxed countercultural spirit of the early 1970s, the Catalog argued that Jews should take religious practice out of the synagogue and into their own hands. It sold half a million copies. It changed the way thousands of readers practiced Judaism. And because it challenged the organization of American Jewish life around large, powerful, and sometimes impersonal institutions, it may have changed contemporary Jewish life even for people who never personally encountered it.

“You didn’t need to have a rabbi for this or that,” said Kern of the Catalog’s lessons. “It started this whole movement of doing it ourselves.”

“By laypeople, for laypeople”

In the fall of 1973, when The Jewish Catalog first appeared on bookstore shelves, the Vietnam War was coming to a close. The unfolding Watergate scandal was eroding public trust in the federal government. Feminists were optimistic about the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have guaranteed gender equality under the constitution. Though the convulsive demands for social change that characterized the 1960s had subsided, the ways of living advocated by anti-establishment hippies and activists were starting to trickle down to the non-Woodstock-attending masses.

One marker of the counterculture’s mass appeal was the success of the Whole Earth Catalog. Created in 1968 by Stewart Brand to sell tools to back-to-the-land communes in California, the publication ballooned into an all-purpose DIY almanac. Though the Whole Earth Catalog, which appeared quarterly until 1972, targeted those on the fringe, it quickly gained popularity among less radical Americans who, while reluctant to give up their day jobs or access to running water, were interested in fermenting vegetables, building a geodesic dome, or forming a community credit union.

In its mission statement, the Whole Earth Catalog emphasized the twin powers of individualism and community. Americans did not have to content themselves with a postwar social order that many found atomized and materialistic. Instead, the Catalog’s statement of purpose contended, each person had the power to “conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested.”

In the Boston suburb of Somerville, a group of young and idealistic Jews were putting those ideas into practice. The three editors of The Jewish Catalog — Michael Strassfeld, Sharon Strassfeld, and Richard Siegel — met as young members of Havurat Shalom, an experimental lay-led community that would eventually inspire a boom of similar spiritual groups across the country.

The havurah’s members dedicated themselves to imagining alternatives to the top-down structures of the mainstream synagogues in which they grew up. Instead of occupying an imposing building, the havurah was located in a yellow clapboard house; instead of a rabbi calling a congregation to order, members took turns starting Shabbat services with Hasidic melodies; instead of a board making decisions, the havurah relied on a non-hierarchical (and often argumentative) leadership structure.

The members of Havurat Shalom, many of whom were also involved in antiwar and other activist movements, were inspired by the broader counterculture unfolding around them: “Everyone owned the Whole Earth Catalog,” recalled Sharon, now 73 and living in Massachusetts. Yet they insisted that they were not so much devising new Jewish rituals but reconnecting with an older way of being.

“We were trying to recapture a more authentic Jewish tradition that we thought had been lost, whether it was in coming to America or moving to the suburbs,” said Michael, also 73, of the havurah’s aims. “And yet we also wanted to be in the contemporary moment.”

Michael and Sharon, who were newly married when they joined Havurat Shalom and have since divorced, offered multiple origin stories for The Jewish Catalog. According to the verifiably true account, Siegel, who died in 2018, proposed a Jewish version of the Whole Earth Catalog as his capstone project for a graduate program at Brandeis. After graduating, he decided to go through with it and brought on Michael and Sharon to help.

Another version of the story is more apocryphal and more symbolic: One day before Sukkot, Michael recounted, several havurah members were sitting around talking about the sukkah they would soon have to construct. Although they had built a sukkah the previous year, no one could remember how they had done it or where they should start now. Someone wondered aloud, “Wouldn’t it be great if there was a book that told you how to build a sukkah?”

In 1971, Siegel obtained a small grant from a local foundation to write The Jewish Catalog and hired Michael and Sharon to work on the project. None of them had any experience writing a book, much less a comprehensive guide to DIY Jewish ritual: For ideas and contributions, they polled fellow havurah members and placed ads in Boston’s alternative weeklies. Even the simplest of topics could provoke debate: For a five-page chapter on challah, the editors had to decide how much history to provide, how to explain relevant Jewish laws in an accessible way and, of course, whose recipe to use.

The one thing the Catalog’s creators knew from the start was what they didn’t want the book to look like. “Up until the Catalog, most information about Jewish life had been written by rabbis or scholars,” Sharon said. The few books that were accessible to lay people provided little practical information. While the havurah members planning their sukkah could have turned to scholarly texts to determine the structure’s prescribed dimensions, they wouldn’t have found much instruction on how to make it stand up. By contrast, Sharon said, the Catalog would be written “by laypeople, for lay people.”

Before The Jewish Catalog was even finished, its editors sold it to the Jewish Publication Society, then under the leadership of the author Chaim Potok. The deadlines stipulated in their contract soon became a source of worry. When it became apparent that they would not finish the Catalog on time, Michael and Siegel deputized Sharon to appeal to Potok for mercy. Reached by phone, the editor reminded her that she had signed “a legally binding contract.”

Sharon interpreted the remark literally.

“I got off the phone, and I turned to the two guys, and I said, ‘We could go to jail,’” she recalled. Chastened and a little bit scared, the trio worked “around the clock,” every day except Shabbat, to meet the deadline.

A Jewish Google

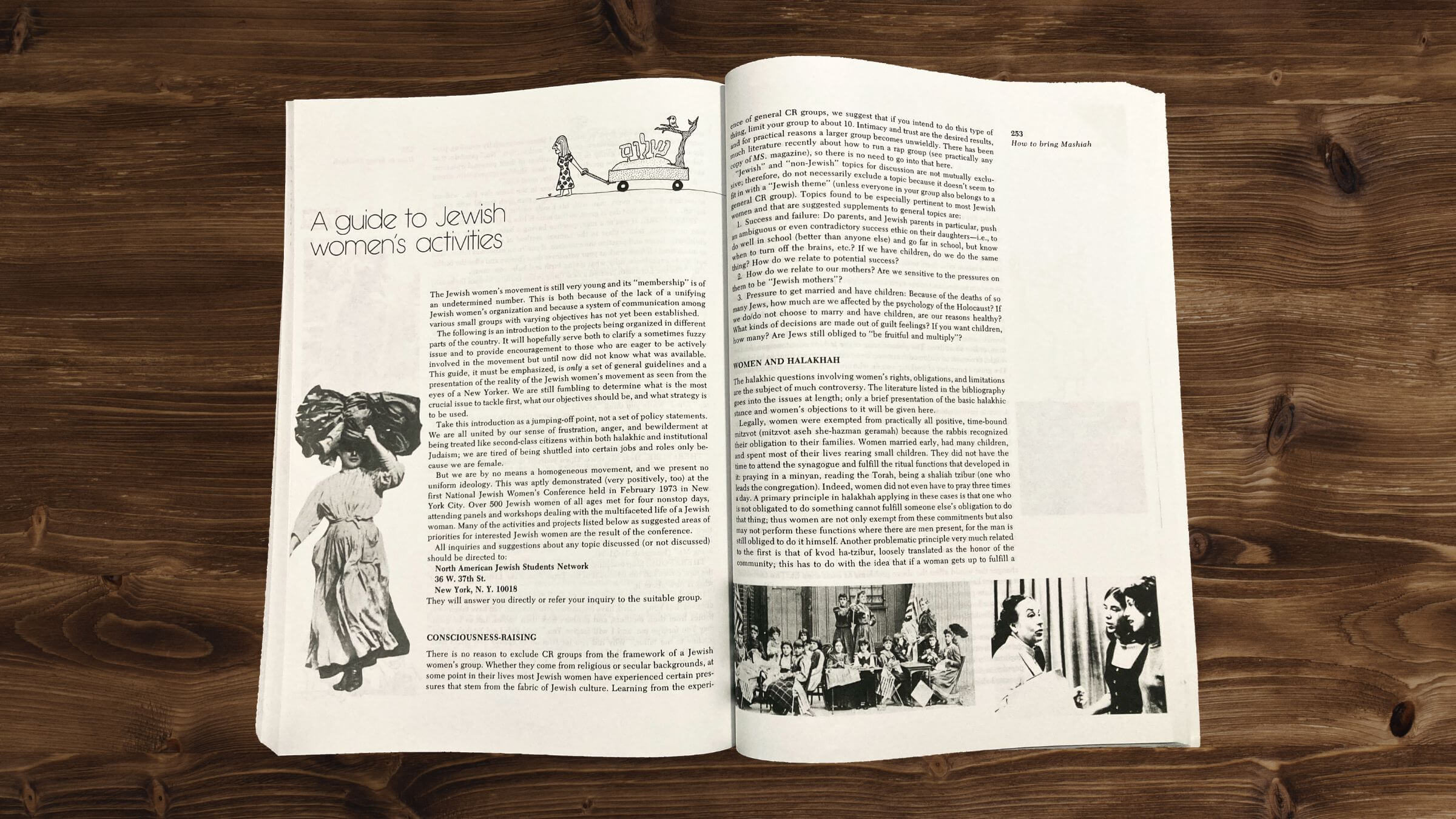

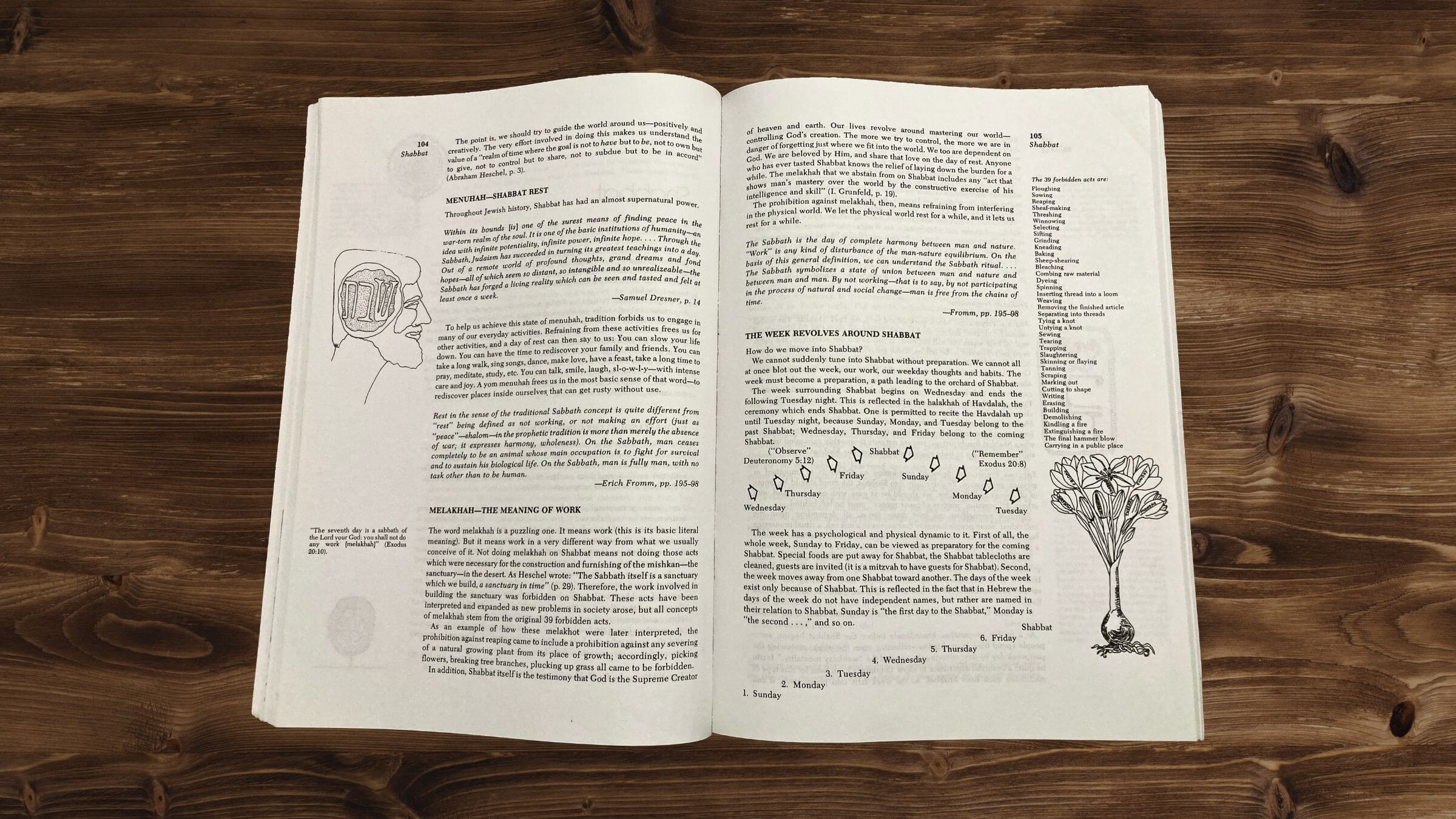

When you open a copy of The Jewish Catalog — at least, the reprinted edition that the Jewish Publication Society still sells today — you will confront a black-and-white photograph of several Jews wearing crocheted kippot and T-shirts with peace signs, dancing barefoot in a meadow to accordion music. They look deeply uncool and supremely beatific at the same time. In the ensuing 318 pages, the Catalog’s many contributors provide step-by-step instructions on replicating this brand of gentle, freewheeling Judaism. Even if you don’t know the prayers. Even if you can’t read the Hebrew letters. Even if, like me, you don’t know a single person who plays the accordion and are alarmed at the prospect of contracting Lyme disease via barefoot outdoor excursions.

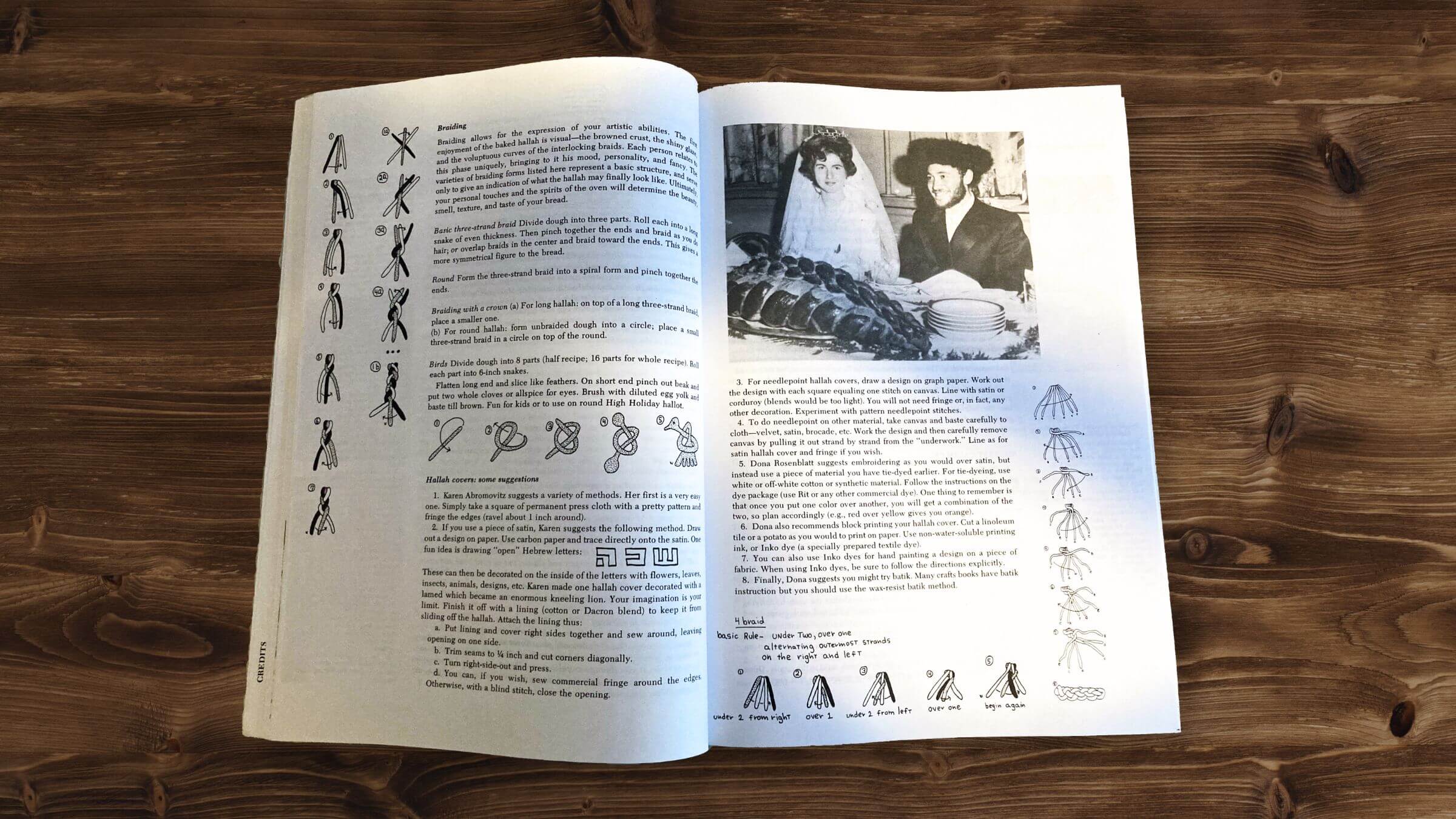

The Catalog’s editors chose a Talmudic layout, with text in the center of each page and photos, graphics, and hand-drawn cartoons lining the margins. Chapters break down the Jewish traditions around Shabbat, holidays, weddings and shiva, explaining the origin of different customs in Jewish law and proposing modern updates: Why buy a menorah from the store when you could carve one out of soapstone or, better yet, build it out of materials foraged in the woods?

In every chapter, commonsense advice vies with zany projects in the soapstone-menorah vein. Sharon’s challah recipe, accompanied by instructional braiding diagrams, is simple and extremely popular: When I surveyed the Forward’s readers on their experience with The Jewish Catalog, the most-cited lessons involved bread-making. Directions for obtaining a ram’s horn, boiling it, and then carving it into a shofar are less easily followed. “The kitchen really stank,” said Michael of his brief experiments on this front.

Many people I talked to described The Jewish Catalog as a pre-internet Jewish Google. Because readers couldn’t exactly surf the web for more information than was offered in each chapter, the Catalog offers, at different points, addresses for different Hebrew jewelers, reputable wedding bands, the head of the London Hillel House, and a Mrs. E.E. Hoisington, who took commissions for handwoven tallit from her house in New Jersey.

Though it’s very much a document of its era, the Catalog also anticipates the confidential tone of a blog entry or Instagram post. A breezy section on traveling in Eastern Europe advises travelers to Warsaw Pact countries to bring “a child’s slate” for the purpose of communicating in bugged hotel rooms and states firmly, regarding Babi Yar, “You will probably be told by your guide that it is very far from the city. IT IS NOT.”

This brisk optimism, present on every page, is at once The Jewish Catalog’s most dated and most charming quality. Yes, the Catalog says, you can build a sukkah from scratch. Yes, you can smuggle Judaica into the Soviet Union. Yes, you can make a menorah from nothing. Yes, you can pressure your synagogue to hold bat mitzvah ceremonies on Saturday mornings rather than relegating them to Friday nights. And if they don’t comply, you can just go and form your own havurah.

A surprise bestseller

Shortly after The Jewish Catalog was published, a story about its authors ran in The New York Times. A first printing of 15,000 copies, according to the article, sold out within a week. Michael walked into the Harvard Coop Bookstore and was astonished to see copies arranged on a prominent table. The Catalog would go on to sell 130,000 copies in 18 months, the historian Jonathan Sarna wrote. Elias Sacks, the current director of the Jewish Publication Society, said that with the exception of the Tanakh, The Jewish Catalog is the publisher’s all-time bestselling book.

Betsy Teutsch, then a senior at Brandeis University, remembered coming back from winter break to find the campus bookstore lined with copies of the Catalog. Teutsch was already sympathetic to the Catalog’s DIY approach to Judaism. For her wedding, just a few months previously, she’d taught herself how to draw a basic ketubah. Though the art of drawing ketubot is centuries old, this was an unusual move at the time: In 1970s America, these marriage contracts generally existed as dry forms handed out by rabbis and promptly forgotten.

In The Jewish Catalog, Teutsch found an entire chapter on Hebrew calligraphy, with instructions on forming letters, using different pens, and even applying gold leaf. The Catalog taught Teutsch what kind of paper and paints to use; and it appealed to her as a feminist because it included the “Lieberman clause,” the Conservative movement’s relatively recent addition to the ketubah text to protect women’s rights in case of a divorce.

As Teutsch improved at calligraphy, her college friends began commissioning their own ketubot from her. When she graduated from college, she turned her hobby into a career, designing ketubot for 45 years.

“Had it not been for The Jewish Catalog, I don’t know how long it would have taken me to get some guidance,” she said.

On the other side of the continent, The Jewish Catalog taught Jonathan Friedan, then 21, how to square Jewish ritual with his anti-establishment values. Disillusioned by the carnage of the Vietnam War, Friedan had dropped out of college two years earlier and moved to an island in the Puget Sound, where he worked as a commercial fisherman and lived in a house without water or electricity.

He didn’t have much religious knowledge, but when a friend gave him a copy of The Jewish Catalog, he found himself adapting its lessons for his remote community. Soon, he was making challah on Shabbat and singing “Lecha Dodi” with whatever “wandering Jews” and non-Jewish friends he could rustle up on the island.

“It was my Shulchan Aruch,” said Friedan, now 71, referring to the most widely used compilation of Jewish law. “I didn’t have anything else.”

“I realized I knew nothing about Judaism”

While The Jewish Catalog was born from the 1970s counterculture, it also appealed to people who lived far from that world — or from any Jewish culture at all.

As a young wife and mother in the early 1970s, Carol Oko wanted to create a more observant home than the one in which she grew up. But she didn’t have much practical knowledge of Jewish ritual, and she wasn’t going to have much in-person support: Because of her husband’s job, Oko moved frequently between rural towns with few Jewish institutions. When a friend gave Oko a copy of The Jewish Catalog, it quickly became “a Bible” for her.

“I lived so isolated,” Oko said. “I depended on it.”

Staying up to peruse The Jewish Catalog while her husband slept, Oko learned the basics of keeping kosher, cleaning her house for Passover, and celebrating holidays at home. She became confident enough to problem-solve on her own, ordering kosher meat from larger cities when she couldn’t find it at local supermarkets.

When the second edition of The Jewish Catalog was published in 1976, its “Jewish Yellow Pages” section, which listed local institutions in cities across the United States, helped Oko plan her family’s moves. “Anytime my husband said, ‘We’re going to move,’ I would go to the book and see if there was a Jewish community, and the list of synagogues and restaurants.”

Jack Shlachter likewise found himself leaning on The Jewish Catalog when he moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico, as a physics graduate student in 1979. Shlachter wasn’t particularly interested in Jewish practice, but he started attending synagogue in order to make friends in the sparsely populated community. When he stumbled on a copy of the Catalog, he was immediately drawn to a chapter called “Creating a Jewish library,” which included basic explainers on the distinctions between Talmud and Midrash, an immense bibliography on such topics as Hasidism and Soviet Jewry, and advice on haggling at Jewish bookstores. (“Hebrew booksellers are not the most gracious of all people.”)

“I realized I knew nothing about Judaism,” Shlachter said. Soon, he was ordering books from the Jewish Publication Society. When friends visited New York, he asked them to bring back books he couldn’t find in New Mexico.

Assembling his library was “disastrous from a financial point of view,” Shlachter admitted. But it was an alternative to what he called “jumbo jet Judaism,” in which a rabbi serves as a “pilot” in charge of the synagogue and congregants are merely spectators — the same problem that the members of Havurat Shalom had identified.

By orienting him in Los Alamos, The Jewish Catalog might have changed the course of Shlachter’s life. Now 69, he still lives in the town. He was ordained as a rabbi in 1995, and now leads the Los Alamos Jewish Center. And he owns 7,000 books.

“It’s not like, leave everything to the experts,” Shlachter said of the Catalog’s message. “Everyone has the ability to become an expert.”

Radical yesterday, mainstream today

Tying tzitzit. Waving an etrog. Crocheting kippot. Making a shofar. Mastering the Hebrew calendar. Forming a minyan. And of course, making challah. The list of skills that readers mastered through The Jewish Catalog goes on, although the more ambitious projects didn’t always turn out as planned: One reader responded to the Forward’s survey that the sukkah he built according to the Catalog’s instructions was “not as stable as we had hoped.”

Today, most of that information can be found via a quick Google search, and those in doubt of their ability to build a structurally sound sukkah can order a prefab kit on Amazon. With the advent of the internet, The Jewish Catalog became an artifact of a bygone time. Many people I interviewed, who once relied on the Catalog, no longer knew exactly where their copy was. If they needed a refresher on a blessing, they could consult Wikipedia, or My Jewish Learning, or Chabad.org. And in many cases, the Catalog had served its purpose so effectively that such refreshers were no longer necessary.

But those dusty, misplaced copies are not the only measure of The Jewish Catalog’s legacy. All three editors moved into long careers in the Jewish world: Michael wrote several more books about contemporary Jewish practice, including, most recently, Judaism Disrupted: A Spiritual Manifesto for the 21st Century; Sharon helped found the Abraham Joshua Heschel School, one of New York City’s most prominent Jewish day schools; Siegel taught at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Los Angeles.

The Catalog’s contributors’ page is studded with other recognizable names as well. Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who co-authored a lengthy chapter on Shabbat, became one of the founders of the Jewish Renewal movement. Arthur Waskow, who wrote a rather abstract chapter called “How to Bring Mashiah,” is the author of the “Freedom Seder” and a beacon of left-wing Jewish activism. The author of that blithely pragmatic guide to traveling in the Soviet Union is the Holocaust scholar and U.S. State Department special envoy for countering antisemitism Deborah Lipstadt. (Then going by “Debby.”)

That many of The Jewish Catalog’s suggestions — artistic ketubot, backyard sukkahs, the wearing of tallit and tzitzit by women — testifies to this generation’s success in bringing once-radical practices into the mainstream. Now, many of the Catalog’s contributors are “elders” to a new generation of progressive Jews, said Sol Weiss, an artist and cultural organizer.

I first met Weiss when reporting on Linke Fligl, a communal farm founded by several queer Jews interested in “land-based” Jewish observance — in other words, a project very close to The Jewish Catalog in spirit. Though Weiss, 31, didn’t know about the Catalog when they lived at Linke Fligl, they saw Waskow as an influence and had worked with Lynn Gottlieb, a contributor to the Catalog’s second edition. When they encountered the Catalog recently through a roommate, the experience was “deeply validating.”

Paging through the The Jewish Catalog, Weiss saw illustrations and cartoons that reminded them of their own art. Writers in the Catalog had directly addressed questions that puzzled the Linke Fligl team, such as how to honor the prohibition against cooking on Shabbat while living off-grid. And the Catalog’s informal, handmade format reminded Weiss of contemporary Jewish zines, including one published by Linke Fligl. Like the Catalog, Linke Fligl’s zine collected writings on subjects often absent from mainstream Jewish discourse — in this case, Weiss said, “land, belonging, and reparations.”

Linke Fligl’s zine is part of a wave of anarchic, progressive organizations that have gained steam in recent years, including the Jewish Zine Archive and the Radical Jewish Calendar. Jess Rosenberg, a Jewish educator with a personal fondness for The Jewish Catalog, said that as the major denominations see declines in membership, DIY Judaism is experiencing a resurgence. She cited Adamah, an organization that provides Jewish environmental education, and Lab Shul, an experimental synagogue in New York, as examples of small-scale projects searching for ways to unite traditional ritual with contemporary life.

“I love the idea of looking at the ritual, breaking it apart, seeing what makes sense for you, as a human being at this moment in time,” Rosenberg said. “And I feel like this is the core of what DIY Judaism is.”

Sharon has long hoped to see a successor project emerge, one that would apply the Catalog’s freewheeling spirit to the modern Jewish experience. “It would be so exciting to work on a project that understood the entire Jewish community — all over the world — as more connected than we saw it in the ‘70s,” she said. “There are exciting projects going on in Hungary and Berlin and Costa Rica, and uncovering those projects for a wide audience would be enormously satisfying.”

So far, no such book has materialized. But Weiss said that the staying power of The Jewish Catalog made them hopeful about the impact that today’s innovations in DIY Judaism might have.

“I felt this time expansion,” said Weiss, recalling their experience reading the Catalog. “Who is going to find the resources we put out in 50 years?”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO