When a Carole King or a Susan Sontag goes missing, it’s good to have a Jewish detective on the case

in ‘The Last Songbird,’ Daniel Weizmann puts a new Jewish spin on an LA noir

Daniel Weizmann’s The Last Songbird is the first in a series of Pacific Coast Highway mysteries. Photo by Istock

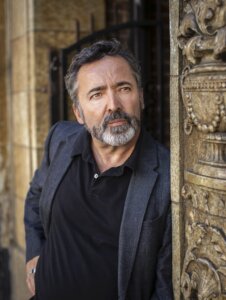

Daniel Weizmann has been writing about music since 1980, when he used his bar mitzvah money to start the early Los Angeles punk fanzine Rag in Chains. So it’s no surprise, then, that The Last Songbird, his debut novel, would revolve around music and the people who make it — even if the main characters in this noir-ish detective thriller are a far cry geographically and artistically from the gritty Hollywood punks that Weizmann cut his teeth covering.

Adam “Addy” Zantz, the novel’s protagonist, is a Lyft driver in his late 30s who still dreams of making it in the music business. He befriends Annie Linden, a legendary-but-reclusive singer-songwriter from the 1970s who regularly calls him to drive her around LA, and who Adam hopes will help him finally get his foot in the door of the biz. But when Annie is murdered, Adam turns detective to try and find her killer — and to keep himself out of prison as an accessory to the crime.

The Last Songbird is an enthralling and often deeply amusing read; it’s a novel that puts a 2020s spin on LA noir in the same way that Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye gave Raymond Chandler a sun-drenched ‘70s twist. Addy’s odyssey takes us from wealthy Malibu enclaves to ugly strip malls to forgotten stretches of Mid-City Los Angeles to gorgeous stretches of the Pacific Coast Highway, as he attempts to untangle the web that somehow connects Annie to a strange array of characters that include Hollywood junkies, showbiz hangers-on, obsessive fans, radical feminists, men’s rights advocates, a dead urologist and a Black hardware salesman with a musical past.

Weizmann’s novel also has a distinctly Jewish flavor. Most of his characters are Jewish, including Addy’s friend Ephraim “Double Fry” Freiberger, who plays one of the story’s most memorable supporting roles. Double Fry, a pot-smoking TMZ photographer in a Grateful Dead yarmulke who spends his free time studying the Torah on his boat The Shechinah, serves as both Addy’s spiritual advisor and the one person he can completely trust when his world seems to be coming apart around him.

Weizmann, who has a second mystery novel in the works, spoke with me about The Last Songbird.

Why did you choose the noir genre for your first novel?

I’m a huge mystery fan. I grew up on old time radio; when I was a little kid, I was a member of SPERDVAC — The Society to Preserve and Encourage Radio Drama, Variety and Comedy — which would send out a newsletter where people would trade tapes of, like, The Saint and Dragnet. So that was my thing, and then I discovered Raymond Chandler. I’ve been trying to write a mystery in earnest since the age of 15, and for a while I just wrote all these bad Philip Marlowe imitations.

Finally, about six or seven years ago, I got the inspiration for this novel. LA has no cab culture, but I always felt that, somehow, my protagonist needed to be a driver; I was trying to do something with a limo driver, but when the Lyft and Uber culture started, I was like, “That’s it.” That was the turning point — it could just be a regular guy that suddenly is behind the wheel.

And as a Lyft driver, Adam gets to see all these different parts of Southern California, and not just the fancy neighborhoods, expensive restaurants and red-carpet affairs.

Totally. My wife is a very successful floral designer, so among my hodgepodge of day jobs I do deliveries for her. And that takes me into some crazy parts of LA — not only the flower market and the whole downtown culture, but also the super-wealthy neighborhoods, where people live like behind six gates, and random parts of LA that you would never have a reason to go to unless you were delivering something. So that was a huge inspiration, as well. There’s a character who sells industrial tools in a part of the West Adams neighborhood, this industrial area with little bungalows hat I would never have known about without that floral delivery gig.

Annie Linden, the aging singer-songwriter who turns up murdered, seems to be an amalgam of several popular musicians from the 1970s, including Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Was there any one in particular who inspired you to make a female singer-songwriter from that era the center of your mystery?

Well, I named Annie after Dreamboat Annie, the Heart album, which has this recurring, semi-rock opera thing about this character who’s kind of out of step with the world around her. But there are also elements of Annie that are pulled from a lot of different women of previous generations that really had the fire of self-liberation. And it’s not just pop singers — it’s Mary McCarthy, it’s Susan Sontag, it’s Anne Sexton. But then among pop singers, there’s certainly elements of the ones you mentioned, these super brilliant women who are powerful and poetic and larger than life.

And Annie Linden is not this person, but the image that came to me over and over again is that first Rickie Lee Jones album cover, where she’s on the beach smoking a little cigarillo or something — she’s like, pure freedom. And I wondered what does it mean to stand alongside someone like that, as a lover, a husband, a child, or even a driver? It’s one thing to be awestruck by it, and then it’s another be alongside it.

Annie isn’t Jewish, but there are quite a few characters in your novel who are. Did you set out to write a mystery populated by Jewish characters, or did that just kind of happen organically?

First of all, I was born in Israel; I’m half Ashkenazi, half Mizrahim or Sephardic, and I grew up in a very Jewish environment. So, anytime I sit down to write fiction, it’s gonna end up being Jewish fiction somehow. And I love Isaac Babel’s Benya Krik stories, and all the gangster-type tough guys that show up in Saul Bellow’s books, so there’s a connection there. And there are some great Jews working in the detective genre too, like Jonathan Kellerman, and the Moses Wine books [by Roger L. Simon]. But what I was also making a direct move on was that my dad was a tough guy; he fought on the front lines in four wars, including fighting with the French against the Nazis in World War II, and fighting in the Israeli Independence War. My love of detectives was really connected to him; we watched The Rockford Files together, Columbo, all of that stuff.

But when I would sit down to try and write a detective story, I would fumble, because I would think of my dad — this Sephardic tough guy who looked almost like Humphrey Bogart — and I’m not that. I’m a half-Ashkenazi kid from LA; a Hollywood kid, a rock kid. So one of the most important lines that I stumbled upon in creating the Adam Zantz character is the line, “I’m about as hardboiled as scrambled eggs.” I wanted to have an amateur detective who is more nebbish-y, more … there’s a Yiddish word I love, luftmensch, which means, you know, his head’s in the clouds. He’s a dreamer; he’s a song guy — but he’s also not that good of a songwriter. Some of his lines are a little bit good, and he knows the popular songbook; but the music business is rough on the innocent, and Adam is an innocent in many ways.

Where did the Double Fry character come from? He’s one of my favorite parts of your novel.

He’s a composite of a few friends, but really one in particular. He was one of these pot-smoking wanderer guys who was starting to gravitate more and more towards religious observance; he lived on a boat in the marina, and he was interested in maritime law — but he was also really interested in Gematria and Kabbalah. That combo of being a modern city guy, but also attracted to Scripture, that whole super-spiritual trip was really interesting to me. Now, is the hippie trip an offshoot of the Abrahamic trip, or is it bringing it back, or what? I’ve wondered about that.

This might be getting too philosophical for this piece, but it’s not an accident that “the 60s” happened after World War II. You could draw a line between the concentration camps and Woodstock; there was a feeling in the 60s of, like, we really screwed up and almost destroyed the planet, and we’ve got to try something else. And that ties directly into Annie’s character — she is really one of those people that came of age in the 60s. So, Double Fry, he’s like our generation, part of the younger generation that wants to try and preserve some of that 60s energy, but it’s just not that easy anymore. To do it now, you really have to live on the edge of the world.

Speaking of the edge of the world: It says “A Pacific Coast Highway Mystery” on the front cover of your novel. Is that the subtitle of this book, or is it the name of a series?

It’s the name of my series, and the second novel is slated to come out in a year. It’s called Cinnamon Girl; I don’t want to say too much about it, except that it involves a very obscure band from [LA’s early 80s] Paisley Underground scene. It takes place in the present, but it involves their old acetate.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO