Why is the name of ‘the most vicious antisemite in the English-speaking world’ still so prominent at Cornell?

The anti-feminist, Jew-hating screeds of Goldwin Smith would seem to be at odds with the school’s College of Arts & Sciences

Students outside Goldwin Smith Hall at Cornell. Photo by Getty Images

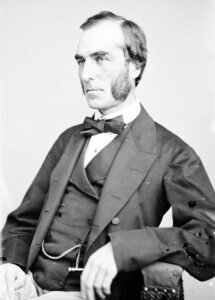

Aug. 13 will mark the bicentenary of UK educator Goldwin Smith, described by one historian as “perhaps the most vicious antisemite in the English-speaking world.” Cornell University’s Goldwin Smith Hall, housing its College of Arts & Sciences, was named in his honor.

At the end of 2020, the Cornell University Board of Trustees accepted a recommendation by a special task force to rename the honorary Goldwin Smith Professorships, currently held by 14 faculty members in the College of Arts and Sciences.

A university statement admitted that Smith “authored many bigoted essays that put forth antisemitic, anti-feminist, anti-suffrage and anti-coeducation views.”

Indeed, Smith called Jews “parasites” who absorb the “wealth of the community without adding to it” and attributed the “repulsion” they provoked in others to their “preoccupation with money-making,” which made them “enemies of civilization.”

Yet the university stopped short of removing his name from Goldwin Smith Hall which, according to the university statement, would be “too simple an action.” Instead, they asked a task force to recommend further action.

Goldwin Smith was a wealthy journalist and academic who never produced any original research or historical publications of lasting value. He donated money and books to Cornell, winning affection and prestige, but taught there for only three years. He left in a snit after the university decided to admit female students.

Smith was ardently opposed to women being given the right to vote, or being educated anywhere but in all-female institutions. After leaving Cornell, Smith moved to Canada where some of his family lived, and there spent decades writing vehement Jew-hating articles.

Typical of Smith’s discourse during Russian pogroms was his lengthy justification of good-hearted Russian peasants who murdered, pillaged and raped in Jewish communities. Smith simultaneously down-pedaled the gravity of the carnage, claiming on no reliable evidence that reports were exaggerated.

Smith depicted Jews as a worthless primitive tribe that had better disappear as quickly as possible, either by total assimilation or forced deportation. At length and in detail, Smith trashed the Talmud and Kabbalah as mostly bilge.

Some Canadian politicians took his arguments seriously, and this may have helped advance the Canadian policy of refusing entry to European Jewish refugees, even to a vast depopulated country, condemning them to be murdered by Nazis to fulfill the Canadian government view that in terms of Jews, “none is too many.”

In 1992, historian Gerald Tulchinsky opined that Smith’s “fulminations amounted to nothing less than an outright assault on the right of people to live as Jews in civil society.” As Tulchinsky noted, Smith “challenged the legitimacy of Judaism and the right of the Jewish people to survive as a distinct cultural group in the modern world. This was antisemitism of the most fundamental and dangerous kind.”

Somehow Tulchinsky’s views did not reach Ithaca, New York. In 2009, Canadian religious studies professor Alan Mendelson argued that Smith was “perhaps the most vicious antisemite in the English-speaking world.” Some Cornell graduates finally began to argue that a name change was overdue for Goldwin Smith Hall.

That year, in a review of Mendelson’s research for the Cornell Alumni Magazine, political theorist Isaac Kramnick and Americanist Glenn Altschuler demurred that Smith was “certainly not ‘the most vicious antisemite in the English-speaking world.’” Yet the Cornell professors conceded that he was “far worse than the ‘genteel’ Jew-haters in turn-of-the-century America and Canada.”

Kramnick and Altschuler reminded readers that the hall had been named in Smith’s honor over a century before, so strong evidence would be needed to justify renaming it. Only in 2020, after race-related consciousness raising occurred on American campuses, did two previously honored Goldwin Smith professors ask to have their names dissociated from the misogynistic antisemite (he hated French Canadians too).

There was precedent at Cornell for snubbing Smith. According to his memoirs, in 1909 at age 86, Smith had hoped to return to campus to lecture, but an expected invitation never materialized; perhaps faculty members had actually read his articles in international periodicals.

Historical opposition to Smith was long visible. In 1881, The New York Times replied to Smith’s attacks on Jewish victims of European pogroms: “It was bad enough to have been persecuted by Kings and abused by German statesmen, but to be pronounced unfit to live, and to have their venerable scriptures danced upon by Mr. Smith, must be the last drop in their cup of humiliation.”

There were refutations in The North American Review, which originally published Smith’s screeds. One in 1891 was from a pseudonymous Isaac Besht Bendavid, who adopted as a middle name the acronym for Baal Shem Tov, the mystic considered to have founded Hasidic Judaism.

Another from the same year was by Hermann Adler HaKohen, chief rabbi of the British Empire, who likened Smith’s opinions to an “ignis fatuus” (will o’ the wisp).

A Presbyterian clergyman, George Monro Grant, complained in 1894 about a Smith book applauding pogroms: “The fault is thrown wholly upon the Jews and not upon those who treat them with brutal violence.”

Of these retorts to Smith, perhaps the most effective were satirical, like the Pall Mall Gazette which in 1897 referred to Smith as a “bilious philosopher” who believed “how wrong everyone is, and what a very superior person Dr. Goldwin Smith must be.”

Even wittier was light verse from 1891, cited by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, a founder of American Reform Judaism. Rabbi Wise termed Smith a “modern Haman” and “theatrical man of absurd prejudices against the Hebrew race,” concluding that “to argue with him would be a waste of time; none can convince him of his fallacies.”

Instead, Rabbi Wise cited a “poetical genius” who had concocted a reply in doggerel: “To solve the Jewish question,/ And make the Hebrew pause,/ Smith offers the suggestion,/ ‘Suppress his Book of Laws.’”

Humor aside, serious uncomfortable questions might be asked about why Andrew White, Cornell’s co-founder, also hired Edward Freeman, another UK historian seen as Smith’s main rival in Jew-hating.

Freeman and Smith detested British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli; the former referred to the political leader as “the dirty Jew.” Smith was motivated by revenge after Disraeli’s 1871 novel Lothair spoofed him as a “social parasite.” Smith returned the insult by repeatedly classifying Jews as parasitical, claiming he drew the term from botany.

More lethal implications arose in 2019 when a swastika was found scrawled on Goldwin Smith Hall. The graffitist’s gesture was oddly apposite, as Smith’s writings had been praised in Nazi Germany in 1942 as “An Anti-Jewish Voice in Victorian England.”

Cornell researchers delving into the topic will likely defend Smith for opposing slavery in America. Smith even paradoxically contributed to the building fund of Toronto’s Holy Blossom Temple in 1897 and attended the opening of the Reform synagogue, possibly to more easily refute accusations of anti-Semitism.

Such nuances may influence the decision of the Cornell task force. But on Goldwin Smith’s bicentenary, to conclude that this Haman’s name is worthy to remain on the Arts & Sciences building would surely contravene university ideals.

Rather than fearing decisive “simplicity” (peshitut), Cornell authorities might look to Jewish tradition to find contexts where it is essential.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO