FIRST PERSONWhy I bought a headstone for a Holocaust survivor I never knew

The dead man was a hustler despised by other Jews. But to honor him was to honor the vanished world of Milwaukee’s Jews

No one wanted to chip in for Josef Hamerman’s tombstone until two decades later. Photo-illustration by Matthew Litman/Forward. Photos courtesy of Stuart Rojstaczer

I asked the monument salesman how long the letters on the gravestone would last. “They’re guaranteed for 900 years,” I recall him saying. “If the letters start to fade after 450, get back to me. We’ll work something out.”

Maybe the guy joked with his customers all the time. Or maybe the tone was because he knew I was buying a gravestone for a man I didn’t really know.

The dead man’s name was Josef Hamerman.

He’d been gone for decades, since 1986. His grave was unmarked. I only knew of Hamerman because my mother had tried to get a collection started for a gravestone back in 1999, when she was dying of pancreatic cancer and trying to tie up loose ends.

Hamerman, like my mother, was a Holocaust survivor who lived in Milwaukee. He probably had been with us at the survivor Sunday summer picnics in Lake Park. Mom was 70 in 1999 when she started calling the old gang to try and rustle up $2,000 for a monument to mark the grave.

“I’ll give $300,” I remember her saying on the phone. “You give whatever you want. Joe Hamerman was one of us. I don’t care what he did. It’s not right that he doesn’t have a stone.”

My mother, born Rachela Erlich in Poland, survived the wrath of Hitler and Stalin as a child. She married the love of her life, and ran a construction business in an era when no women ran construction businesses. But her effort to get a stone for Joe Hamerman came up empty.

‘He was no good’

“I won’t give a penny,” one person said. “He was no good,” responded another. “He deserves what he got.”

After a half-dozen calls, my mom was crushed.

Who is Joe Hamerman? I asked. He was a greener, she explained, adding that he had helped my grandfather in Germany after the war.

Greener is Yiddish, and literally means “green ones.” It’s a term for any neophyte, and in this case meant people fresh off the boat like my parents and their friends. Helping my grandfather probably meant that he helped my mother’s father, Frank — Fajwel in Polish or Yiddish — run guns for the Haganah from Czechoslovakia to Italy. Maybe he drove a truck; my grandfather was a terrible driver.

“He married a Jewish girl here, an American,” mom said. There was a negative assessment in her tone. The most consistent insult and admonishment my parents ever threw my way was that I was “thinking like an American.”

“Then he went crazy, divorced her, and married a Krist,” mom continued, using the Yiddish for Christian. When Hamerman died, she said his Christian wife stiffed the funeral home, and moved to Florida with her husband’s money.

Was it a lot of money? I asked.

Hardly any, she said. But it should have been enough to pay for a funeral.

‘We’ll split the cost’

My mother died six months later. We buried her next to my father beneath a shared stone of red granite.

I didn’t hear the name Hamerman again until January 2022, when mom’s kid brother, Josef Erlich, called from Milwaukee. Uncle Joe was born in Tomaszów Lubelski, Poland, in 1938, and understood that his survival during the war was miraculous. Growing up, I sensed he was convinced God had done everything possible to kill him as an infant, given up in exasperation, and would never touch him again.

But when Joe called in 2022, he’d just gotten over a horrible bout of COVID and, for the first time, was talking about his eventual demise. Then he blurted: “We need to get a stone for Joe Hamerman.”

It took me about two seconds to remember the name. Did he realize mom had tried to get a stone for Hamerman 23 years before?

He did not.

“She tried to get a collection going from the greener,” I told him.

“Those schnorrers?” he snorted. “She didn’t get anything, did she?”

She did not.

“I know what they said. ‘A shlekhter, farhayrat mit a Krist. Im? Fardinen gurnisht.’ Am I right?” My uncle did, indeed, know his people well.

This was our usual way of speaking. We are the last of the Milwaukee Yinglish speakers — or, as my uncle says not infrequently, “the last of the Mohicans.” What he’d imagined the old gang saying was that Hamerman was a lazy, untrustworthy ne’er do well who married a Christian and didn’t deserve anything.

Now that he knew my mom had wanted to get Hamerman a stone, he was all in. “You and me,” Uncle Joe declared. “We’ll split the cost.” My uncle was a businessman through and through, someone who had turned his father’s junkyard into a large metal recycling facility. He knew how to cut a deal.

Two weeks later, a UPS envelope arrived at my home in Palo Alto, California, containing 100 $20 bills. I was in for another $2,000 — if the stone cost less than $4,000, he told me, give the extra to charity.

It was my job to procure the stone as well. First, though, I had to find out where Josef Hamerman was buried.

The geller and the greener

In the six years after World War II ended in 1945, a few hundred Holocaust survivors settled in Milwaukee. They formed a community on the city’s West Side that had four Orthodox synagogues, three kosher butchers, a place to procure Shabbat candles or a bar mitzvah tallit, a Jewish nursery school and a Jewish burial society.

That’s where I was born, in 1956. For what it’s worth, Gene Wilder grew up in the same neighborhood and his father, a Russian Jew who emigrated long before the war, still lived there when I was a kid. Most people I knew spoke a rapid-fire mix of English and Yiddish, frequently peppered with Polish, Russian and Hebrew.

If you didn’t speak two or three of those languages, you’d often and intentionally be left out and lost. I had two-and-a-half: English, Yiddish, and a childlike Polish. As time went along, I picked up a bunch of Hebrew.

The established community of Jews in Milwaukee shunned newcomers like my folks, fearful that their old-world ways and heavy accents would somehow harm their own efforts at assimilation. We called the already-settled Jews der geller, the yellow ones — they were like ripe bananas. My parents and their friends were proudly der greener, the green bananas.

My uncle is one of the few Milwaukee survivors alive today. Almost all of them are buried in Beth Hamedrosh Hagodel Cemetery, which is more or less across the Interstate from the city’s Major League Baseball stadium.

I visit the cemetery every time I’m in Milwaukee. My parents and grandparents are there. All the parents of my childhood are there, and also my childhood rabbi, Jacob Twerski. I try not to go during rush hour. Between the boom-boom from the strip club next door and the cars whizzing by, it can be hard to think clearly.

Finding the unmarked grave

I called the director of that cemetery and asked: Is Josef Hamerman buried there in an unmarked grave?

He paused to look through a list of names on his computer. No, came the answer.

I wasn’t going to give up that easily. How many people have unmarked graves? I asked.

Thirteen, he said.

I asked him to read me their names. The cemetery man was an agreeable sort, and apparently not in any rush. One of the names was Joseph Hamilton. Hold on, I said, thinking: What kind of Orthodox Jew has “Hamilton” as a last name?

When was Joseph Hamilton born? I asked.

He did not know.

When did he die? 1986.

It had to be my guy.

A hustler and a lost soul

Twenty years ago, maybe even 10, proving that Joseph Hamilton and Josef Hamerman were one and the same person would have taken a lot of work and might have been impossible. But today, everybody seems to have at least one relative interested in genealogy who has posted information online. I typed “Josef Hamerman” and “Joseph Hamilton” into a search engine and a link to a family tree came up instantly. Its creator was Hamerman’s ex-wife’s nephew.

I emailed the ex-nephew and asked if his Josef Hamerman and Joseph Hamilton were actually one person — and if Josef/Joseph Hamerman/Hamilton was a Holocaust survivor who had lived in Milwaukee. He emailed back that same day: Yes.

Apparently Hamerman had married and divorced his first wife twice. The first wedding was in Milwaukee in 1951, the second in the Chicago suburbs in 1957. (The divorces were in 1956 and 1966.) I couldn’t find records for when and where he married his second wife; by then he’d changed his name, and there are too many Joe Hamiltons in the world.

The ex-nephew sent a group photo from a family wedding in which Hamerman, short and in a dark suit, looked like a pudgy version of the Hungarian-American actor Peter Lorre, who himself fled Europe when Hitler came to power.

I called my uncle and asked what he remembered. Apparently Hamerman used to come to dinner at the family’s apartment. “Your grandpa took him in,” Uncle Joe said, “thought he was a lost soul.”

This I found interesting. My grandmother was the worst cook in the world. My zayde had taught me how to surreptitiously toss the food she cooked for dinner — he would often come to our house to make up for missing calories. Hamerman must have been awfully lonely to sacrifice his taste buds in exchange for company.

Uncle Joe also remembered that Hamerman had bought a popular restaurant near the apartment at 13th and Cherry. “He ran it into the ground,” Uncle Joe said.

I asked the ex-nephew for more information and to see if any other relatives of Hamerman would talk to me. A month later, another relative of the ex-wife sent this via the ex-nephew, asking to remain anonymous: “Joe was a hustler and did any job that he could get. He tried and usually failed at many business opportunities, including the restaurant.”

This had to be the guy with the unmarked grave.

Plucked from the fire

My uncle wanted to get Hamerman a fancy tombstone, with an etching of Josef’s face. But that sounded expensive, and the one photograph I had was of poor quality. It also seemed altogether too Russian. I had learned that Josef was born in Boryslaw, Ukraine, in 1926. Back then, Boryslaw was part of the Polish Second Republic. Like my mother, who was born three years later, Hamerman had probably grown up speaking Polish; my mother didn’t learn Yiddish until she and her family were shipped off to a Soviet gulag in 1941. Josef was a Polish Jew. He needed a Polish Jewish style monument like the ones my family had. Simple, made of red granite.

I went online and dug up more information. Hamerman had changed his surname to Hamilton in 1955, according to a Los Angeles U.S. District Court document; no reason was given. I wanted to put his father’s name on the stone, and found it by asking someone in Milwaukee’s City Clerk office to look up Hamerman’s first wedding certificate from 1951. Yitzhak.

My uncle wanted the monument to say that Hamerman was a Holocaust survivor, which I thought was odd because none of the gravestones for our family had such information. I consulted the son of my childhood rabbi, Michael Twerski, who is also a rabbi. He suggested a biblical phrase, from Zechariah, “Ud mutzal me’eish,” which translates to a “brand plucked from the fire.”

I liked that. I’d seen the same phrase on a tombstone of one of my parents’ friends. Like every other tombstone of the greener, the only English words would be his name. But which name?

Did you ever hear him use the name Joseph Hamilton, I asked my uncle.

He had not.

We went with Joseph Hamerman: the Americanized spelling of his first name and his original, immigrant surname.

‘These Americans think like babies’

I’d gone down the internet rabbit hole to read the memorial book of Boryslaw. It included personal narratives from the ghetto where Hamerman lived after the Germans invaded Russia in 1941.

Boryslaw’s Holocaust story was similar to the one I knew well from Volodymyr-Volynsky, 140 miles north, where my father, Lazer — Leon in Polish and English — is from. My father, like Josef Hamerman, lost his entire family in the Holocaust.

The handful of survivors from the mass murders in Boryslaw between 1941 and 1943 were shipped off to Mauthausen, a concentration camp in Austria. Josef Hamerman was among them, along with one of his relatives who died in the camp.

Many Americans have a bare-bones and distorted knowledge of Holocaust history. They’ve heard of one camp, Auschwitz, and of one survivor, Elie Wiesel. Maybe they’ve met a few people with tattooed numbers on their arms. They seem obsessed with silver linings about the Holocaust: people saved, gentiles behaving bravely.

I used to snarl inside when I heard people talk about the great wisdom of survivors they had met. Now I understand they were simply trying to show their humanity and kindness. My mother used to get exasperated about these sentiments too and say to me, “Giloibt tzi Got! These Americans think like babies.”

No magical wisdom from suffering

I grew up around Holocaust survivors. I saw them at shul every week. They were my parents’ friends. Few had serial numbers because systematic tattooing was only done at Auschwitz. There are no silver linings. There is no magical wisdom gained from suffering and losing your grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles and siblings.

Holocaust survivors watched over me when my parents were busy in the family business, originally called Lee-Rae Builders, after my parents, and later changed to RPS Builders, for my mother, Rachel, brother Paul and me, Stuart. (I was named for the ship my mother arrived on at Ellis Island, the U.S.S. Stewart, but the nurse in the hospital told mom that “Stuart” was spelled with a “U.”)

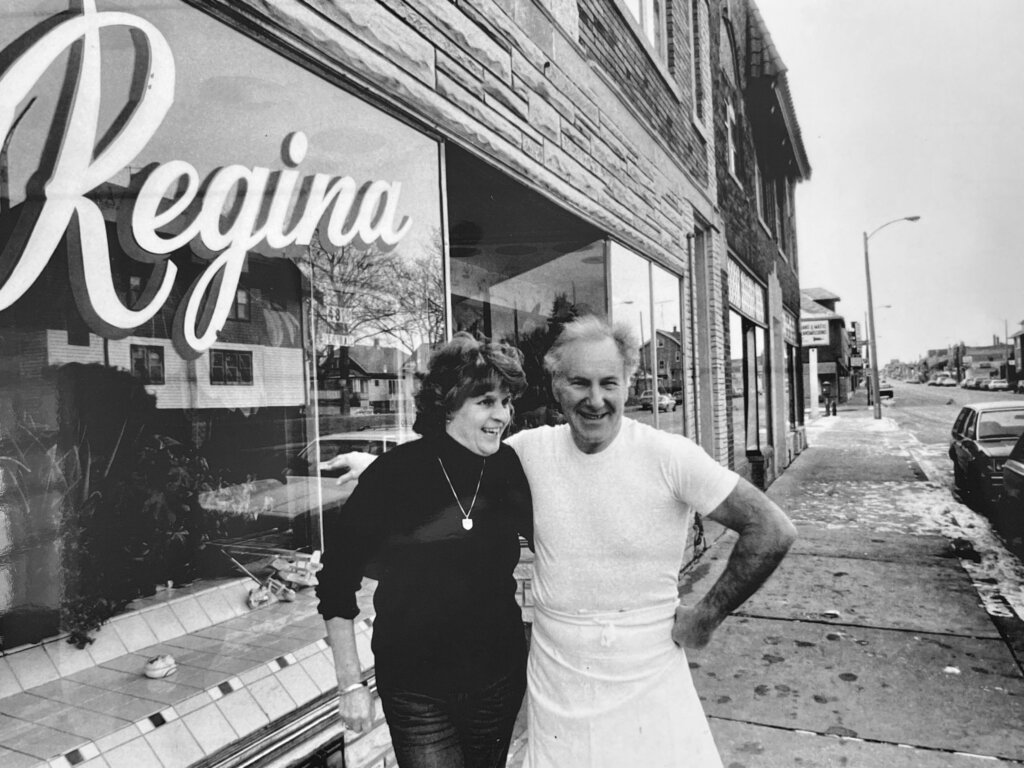

Survivors educated me when I wasn’t in school. Many fed me, especially Elenor Salomon — whom my mom first met in Germany, where both were refugees after the war ended and both lived until about 1950 — and her husband, Otto, who owned Regina’s Bakery.

I am who I am — a retired Duke University professor of geophysics, a novelist and memoirist —because of their collective attention. It took an Americanized shtetl in the wholesome yenne velt — Yiddish for nowheresville — of the Midwest to make me. For 44 years and counting, my wife has teased me about my self-confidence. I know its roots are in this remarkable group of people who constantly told me that I could do anything I wanted — and that I better do something significant to make up for all those lost in the war.

Places full of kvetching and intrigue

Milwaukee’s West Side was one of more than 100 communities of Holocaust survivors across North America. As a kid, we traveled frequently to Chicago’s Rogers Park, and I spent a week in the Fairfax District of Los Angeles when I was 7 — they felt a lot like home. Even Sheboygan, the Wisconsin town where my father first settled upon arriving in the U.S., had a tiny shtetl of survivors.

These were vibrant places full of gossip, kvetching and intrigue, with men and women possessing boundless, twitchy energy. Most were eager to hear and tell a good joke, and all had an eye out for danger.

Many of these communities thrived until the 1970s, when their residents started to die off or move to more prosperous neighborhoods where only English was spoken. What exasperates me is that these American shtetlach have largely been forgotten. We may remember the Holocaust. But we are casually and maybe willfully forgetting the post-Holocaust lives of those who survived.

These people, including my parents, had flaws undoubtedly exaggerated by their experiences in the Holocaust. But the admiration I had as a child for the people in this community remains. They tended to be smart and quick. They took care of their own with an intensity I’ve never seen matched.

So, yes, I felt I owed it to Josef Hamerman, to the greener, to take one person off that list of unmarked graves.

The monument was finished and installed in October. I had wanted to have an unveiling ceremony. But Uncle Joe was in Phoenix for the winter. I hadn’t lived in Milwaukee in 50 years and knew hardly anyone; so I found myself in Beth Hamedrosh Hagodel Cemetery by myself on a Sunday morning. At least the strip club was closed.

It was a cloud-filled, damp day — sweater weather. I started at my parents’ graves. Moss obscured their monument’s lettering. It felt surprisingly satisfying to get on my knees and, with the scrub brush I’d brought and a gallon jug of water, see the moss peel off with every stroke.

While my parents’ monument dried, I walked to the grave of my father’s decades-long enemy, Marv — in Yiddish, Mendel — Tuchman. They had come from the same Polish town, of course. They had both been builders, and had briefly been business partners. That two out of the 100 survivors from Volodymyr-Volynsky had refused to say a word to each other for years was as essential a part of Milwaukee’s greener community as the daily acts of kindness and generosity I observed.

I had asked the cemetery staff where, exactly, Hamerman was buried and hadn’t received an answer. But from my many visits, I knew where graves from the 1980s would be located. I found the new monument inside of two minutes.

It was made of red granite, similar but paler than the monuments for my family.

The final monument

As I stood there, I thought about another monument — a massive, raw, and uncarved, save for the presence of a large Star of David near its maximum height, block of rock in the Jewish cemetery of Tomaszow Lubelski, the birthplace of my mother. Erected in 1993 by the community’s survivors who live in Israel, it honors both those buried in the cemetery and those who were gassed in Belzec.

Jews no longer live in Tomaszow Lubelski. That block of rock is the community’s final Jewish monument. Almost all the prewar tombstones from that cemetery — including those of my mother’s relatives — are missing, taken by the Nazis to pave local streets.

I placed a pebble on Josef Hamerman’s grave, chanted the Hebrew memorial prayer El Malei Rachamim, and recited the Mourner’s Kaddish. There were no tears from me, just an odd sense of a job well done. Then I looked around for the grave of Elenor Salomon, my mother’s friend who owned the bakery. I couldn’t find one.

The last time I had gone to Elenor and Otto’s bakery was in 1999. I was with my nephew, Alex, who was 8 years old and lived in Maryland. We walked around the old neighborhood and he took it all in as if we were visiting the real-life version of the TV show The Wire.

‘You came for the cheesecake, right?’

Milwaukee’s West Side is a mostly Black neighborhood now, where working-class families have gone from good union paychecks to lousy hourly wages. There is still a Jewish day school, and a few Orthodox Jews sprinkled around, including some who have moved to the suburbs but maintain a house where they spend Shabbos. There is only one shul now, Beth Jehudah, run by the younger Rabbi Twerski.

The neighborhood was rundown: masonry mortar was missing, bricks had fallen off houses, paint was peeling off wood siding. As I thought back, I realized it had been pretty rough when we lived there, too.

I’d buzzed the door of the bakery. As Elenor let me in, the glass in the aluminum door rattled. She gave me a kiss that I knew left a big mark of lipstick on my cheek, and shouted to her husband in back to come see me. Elenor was disappointed to hear Alex was not my son, but buoyed when I told her I had a daughter.

“I have cancer here,” she said and pointed to the back of her neck. “I’ll probably be dead in a year.” This was so typical, hearing real news mixed with chitchat. Her husband, Otto, came to the front of the bakery with a piece of mandel bread, which he threw to my nephew. The boy was getting an education.

“You came for the cheesecake, right?” Otto said to me. “You always liked the cheesecake.” There was nothing better on this planet.

The suitcase she carried

The Salomons were married in my parents’ Milwaukee apartment in 1952. They didn’t have money for a formal wedding. The apartment building was torn down long ago, and is now an empty lot next to a freeway. The two-flat where my parents lived when I was born was torn down long ago, too.

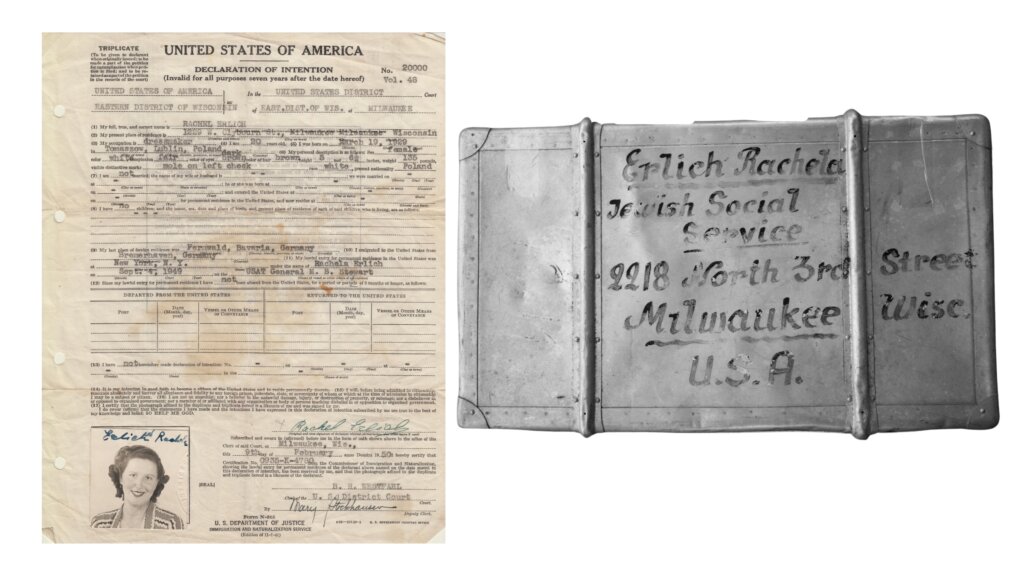

The morning after visiting Hamerman’s grave last fall, I went to the Jewish Museum Milwaukee, which wanted to create a display about my mother. I’d brought some of my mother’s papers, and photographs of her. The thing they were most interested in was the suitcase she had carried with her from Europe in 1949.

It is aluminum, with her name and destination painted in large black script on the outside: Rachela Erlich, Jewish Family Service, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

I’d rescued the suitcase from my grandfather’s basement when I was about 10 and he was threatening to dump it in the junkyard he ran. It was dented and broken, but I knew it was important. My mother carried it with her from house to house until shortly before she died, when I took it to my home in North Carolina, and later, when I retired, to California. Now it was going to be in a museum.

Most of the exhibits at Milwaukee’s Jewish Museum, not surprisingly, showcase der geller, the Jews who came to town well before the war and mostly shunned my parents and other survivors. Most of the memorabilia and biographies feature men. Now there was going to be a display devoted to my mother, a greener and one of very few women of her day who ran a successful business in town.

The display, which will eventually include a video of me telling my mother’s story, is to my mind, an act of defiance. My mother not only survived the war, but thrived in Milwaukee.

And what of Josef Hamerman, a failure and a hustler? His monument in the local cemetery says that he was a vital part of the community too.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO