She was the most famous Jewish actress of all time — can we still say she was the greatest?

Sarah Bernhardt wowed audiences with her performances as Shylock and Hamlet, but a century later only scant evidence of her genius remains.

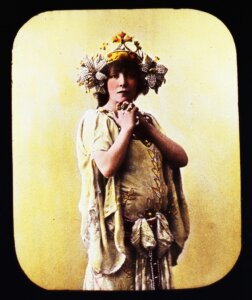

Sarah Bernhardt in a 1913 production of Camille. Photo by Getty Images

On the centenary of her death in 1923, the French Jewish actress Sarah Bernhardt is being honored with a new book by film historian Victoria Duckett examining how Bernhardt transcended her humble origins to become a still-remembered superstar.

As Duckett notes, Bernhardt was the “daughter of a Jewish courtesan” who nevertheless “catapulted herself to international fame and respectability.”

Part of this respectability, as a new exhibit on view at the Petit Palais museum in Paris through Aug. 27 demonstrates, was lavish glamour. Bernhardt epitomized a universal aspiration to cultural expression which audiences took to heart internationally.

Bernhardt’s penchant for playing male roles made her one of the few touring actresses to portray both Portia and Shylock the Jew in excerpts from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

A 1916 review in The Brooklyn Eagle implied that Bernhardt made no attempt to humanize Shylock in any philosemitic way, deeming her incarnation of the money lender “a fiendishly cruel and vengeful Jew … It glares with diabolic hatred at the Christian merchant, eyes glistening … in anticipation of his gory vengeance.”

Earlier, in 1905, in Racine’s Esther, she opted to play the role of King Ahasuerus. The eponymous heroine, a Persian Jewish princess, saved her people by marrying the king.

Bernhardt was proud of her Jewish origins, perhaps because they were intimately linked to women who were important in her life: her mother and Orthodox Jewish maternal grandmother. In 1869, Bernhardt invited her grandmother to move into her Paris apartment to help with childcare.

And during early career upheavals, for a time Bernhardt followed the professional path of her mother as courtesan. Bernhardt took on a series of paying male paramours, including Jewish banker Jacques Stern and Charles Haas, the French Jewish dandy who inspired the character Charles Swann in Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time.

More publicly, Bernhardt was also a staunch advocate of Capt. Alfred Dreyfus, the French Jewish officer unjustly charged with treason, whose trials impacted modern French history.

In addition to political activism, Bernhardt, mostly celebrated for splashy classical roles, dreamy symbolist fantasies and tear-jerking melodramas, could demonstrate interest in plays with social significance. In 1897, she premiered The Bad Shepherds by Octave Mirbeau, about striking factory workers.

Her stance in the Dreyfus Affair may have aggravated latent antisemitism in French audiences. As literary historian Sharon Marcus observed, Rachel Félix, a French Jewish actress of a prior generation who served as inspiration for Bernhardt, did not face the same degree of public obloquy that Bernhardt braved.

As a result, in 1871, after the Franco-Prussian war, Bernhardt felt obliged to address rumors that she was a German Jew. Her reported response: “Jewish most certainly, but German, no.” To a journalist from Le Figaro, she added: “All my family come from Holland. Amsterdam was the birthplace of my humble ancestors. If I have a foreign accent — which I much regret — it is cosmopolitan, but not Teutonic. I am a daughter of the great Jewish race, and my somewhat uncultivated language is the outcome of our enforced wanderings.”

A memorable 2005 exhibit at New York’s Jewish Museum included caricatures from the French press of Bernhardt with a hooked nose, although her nose was in reality straight. She was also shown standing on gold coins, in another stereotype of acquisitive Jews.

Memoirs of Sarah Barnum (1883) a scurrilous novel by a rival actress, claimed that the character inspired by Bernhardt, “like a true daughter of Israel, was filthy.” Further age-old antisemitic stereotypes could be found in Sarah’s Travel Letters From Three Continents by Ottokar Franz Ebersberg, an Austrian journalist.

This fictitious correspondence, cited by literary critic Sander Gilman, depicted Bernhardt as plotting with other leading international Jews, including British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, to dominate the world. In one letter, this specious Sarah reflects to Disraeli that the essence of Jewish womanhood is to pose a mortal threat to non-Jewish males, as in the story of Judith and Holofernes.

Regardless of this vituperative discourse, Bernhardt’s far-flung world tours included trips to places where Jews were mistreated. Only rarely did she confront angry Jew-hating mobs objecting to her heritage, as during one tour to Ukraine in 1882, coinciding with antisemitic pogroms there.

When she returned home, Bernhardt was ever-ready to collaborate with Jewish colleagues, like author Marcel Schwob, who translated Shakespeare’s Hamlet for Bernhardt to perform the title part (theatergoers will recall the 2018 Broadway staging of Theresa Rebeck’s play Bernhardt/Hamlet, which featured Janet McTeer).

And as cultural historian Jonathan Freedman asserted in The Jewish Decadence, Bernhardt was passionately supportive of the young Jewish dancer/actress Ida Rubinstein.

Amid this Yiddishkeit, perhaps paradoxically, from her childhood on, Bernhardt identified as a Catholic. She received her first communion in 1856, attended Notre Dame du Grandchamp, a convent school near Versailles, and aspired to be a nun. As an adult, Bernhardt observed the Catholic prohibition of divorce to the point of remaining wed to an estranged, morphine-addicted husband.

So apart from her still-thriving legend, what traces of Bernhardt’s artistry can Jewish admirers cherish now? Like immortal Yiddish theater tragedians whose greatness cannot be ascertained from technically primitive films and recordings left to posterity, Bernhardt’s power as a performer is best taken on faith or from written descriptions.

Her silent films are marred by melodramatic gestures and her primitive sound recordings betray an overdone vocal vibrato. Instead, documentary footage of her funeral procession through Paris captures a sense of her importance to contemporaries, and the loss and grief they felt at her demise.

One devotee, Sigmund Freud, wrote in 1884 that he “believed immediately everything” she said onstage, but this verisimilitude cannot be found in her onscreen appearances. When filmed speaking in 1915 to colleague Lucien Guitry in what was apparently intended as an unguarded, behind-the-scenes moment, Bernhardt seems ill at ease and affected.

And in her very last role in 1923, taken at the request of Lucien’s son Sacha Guitry, she overdoes a deathbed scene even by silent film acting standards, despite the fact that she was genuinely close to death at that point.

So to truly understand the importance of Bernhardt, it is essential to examine her impact on others, including those who loathed her. Less than two decades after thousands of acolytes crowded the streets of Paris to pay homage to the dead diva, in Nazi-occupied Paris the Jewish actress’ name was unceremoniously removed from the theater once named in her honor.

Although the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt temporarily regained its name after the war, it has gone through a series of renamings since then, most recently to the generically uninspiring Théâtre de la Ville. No French cultural official considers it a priority today to restore Bernhardt’s name to what was once her theater.

Indeed, amid ever-increasing Gallic antisemitism, French civil servants might consider it far too provocative to have such a central cultural landmark named after a performer of Jewish origin.

In this way, Sarah Bernhardt’s majestic and ever-fresh persona, inextricably linked to her Jewish identity, continues to startle and unsettle culture mavens.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO