He was Germany’s most popular playwright — here’s why you may not have heard of him

Jewish writer Ernst Toller lived the radical ideals he expressed in his plays

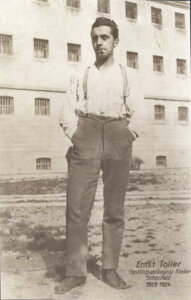

Ernst Toller (background) in a crowd listening to economist Max Weber.

In the spring of 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Bohemia and Moravia, the Spanish Republicans lost to Franco and, on May 22nd, in his room at the Mayflower Hotel in New York, the German Jewish writer and antifascist Ernst Toller, who was living in exile, took his life. Given to prescience, it’s possible he sensed what was coming.

Toller was unique even in the highly political Weimar art scene, for living out his ideals, and their consequences, before his rise to fame as an artist. In 1919, the same year his first play debuted, he served six days as the president of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, an unrecognized socialist state in Munich. He was arrested and stood trial for high treason soon after.

“He was very lucky to not be murdered by the paramilitary right wing as some of his comrades were,” said Drew Lichtenberg, a dramaturg who is releasing his translation of Toller’s 1927 play, Hoppla, We’re Alive! this month.

Toller spent 1920 to 1925 imprisoned at a fortress in Niederschönenfeld. From there, he wrote expressionistic plays and poetry and became perhaps the most famous dramatist in Germany. Toller didn’t see his prison-penned work onstage until his release, but by then he’d been produced in other countries, too, emerging as the most internationally produced German playwright.

Hoppla follows a group of revolutionaries jailed in the 1919 (the year of Toller’s arrest) and their lives eight years later (which was the present day at the time of the play’s premiere). Focusing on a protagonist, Karl Thomas, who was put away for years in a mental institution, the play drew from Toller’s experience with confinement and reflected his disillusionment with party doctrine after freedom. Thomas is a flawed hero, hewing to outdated ideals in the face of a modernizing Germany.

“Toller wasn’t dogmatic,” said Kirsten Reimers, a Toller scholar at the University of Magdeburg in Germany. “He wasn’t writing for a party. He was a freethinker. He looked behind settings and beliefs to find his own conviction.”

Toller’s first play, 1919’s Transfiguration followed a soldier’s return from World War I and ended with the main character sermonizing about socialism, impressing director Erwin Piscator, who would later reference its visual language — including skeletons and scenes from the trenches — in his staging of Hoppla.

Masse Mensch, Toller’s best-known drama, was about a female revolutionary, staged with an enormous cast, and secured his place as a master of expressionism. Observing events from a distance, Toller wrote a 1923 one act, Wotan Rising, inspired by Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch, making him one of the earliest writers to see the threat of Nazism for what it was.

Following his release, Toller continued to channel the mood in Germany. In 1927’s Hoppla, he depicted strains of antisemitism, and even has a character discussing a master race and forced euthanasia.

“You feel this window cracks open where you can catch a kind of a whiff of history as it was,” said Lichtenberg.“He’s interested in the radicalization of young German people by the Nazis and he’s interested in how this cancerous ideology that goes back to the end of World War I among the right is festering and is becoming something warped and demonic.”

But Toller was also skeptical of Communism. His refusal to fall into a party line led to a rift between him and the Marxist Piscator. Creative differences led each to staged different premieres of Hoppla, two days apart, with alternate endings. In a first, both endings are presented in Lichtenberg’s translation.

Piscator’s Hoopla was a massive production that introduced many of the trademarks he’d go on to refine later in his career. The show made use of newsreel interludes, catching the attention of a young Bertolt Brecht, who would become Piscator’s dramaturg and major creative partner in developing a theory of Epic Theatre.

With the Nazi rise to power, Toller escaped to London and then New York. He became a well-known antifascist lecturer, speaking on behalf of Spanish Republicans and raising money for their cause. In the spring of 1939, Piscator visited Toller in his Manhattan hotel. He was starting the Dramatic Workshop at the New School and wanted Toller to be on faculty.

But Toller had sunk into a depression over the news of Franco’s victory and that his brother and sister were shipped to concentration camps. He hanged himself four months before the start of World War II. His early death, and monumental works by Brecht and Piscator, made him a lesser-known figure today.

“If Brecht had died during World War II, before Galileo is staged on Broadway, he gets remembered as an obscure, Weimar Republic, political writer, just like Toller,” said Lichtenberg.

Reimers says that Toller is still well-known in Germany, Italy, Spain and India (Toller had a correspondence with Jawaharlal Nehru). But it was only in 2015 that his complete works returned to print, an initiative of the Ernst Toller Society, based in Neuberg, where Toller was imprisoned. Part of the reason he’s not as well-known as Brecht, Reimers believes, is his subject matter. While Brecht set his plays in China or during the Thirty Years’ War, Toller “was too bound to German society in the ’20s,” Reimers said.

But Toller’s influence can still be seen, even in unlikely places. The main character of Paul Schrader’s 2017 film First Reformed is a pastor named Ernst Toller, whose faith is challenged by his fears of environmental collapse.

“Why does he have the name of a famous German expressionist revolutionary poet, who happened to be Jewish?” Lichtenberg wondered, then ventured a guess. “That character is alive in a pained way to what’s going on in the world.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO