How these Dutch Jewish artists aided the resistance with children’s books

While hiding from the Nazis, a husband and wife published dozens of children’s books anonymously. Now, you can see them at a New York book fair

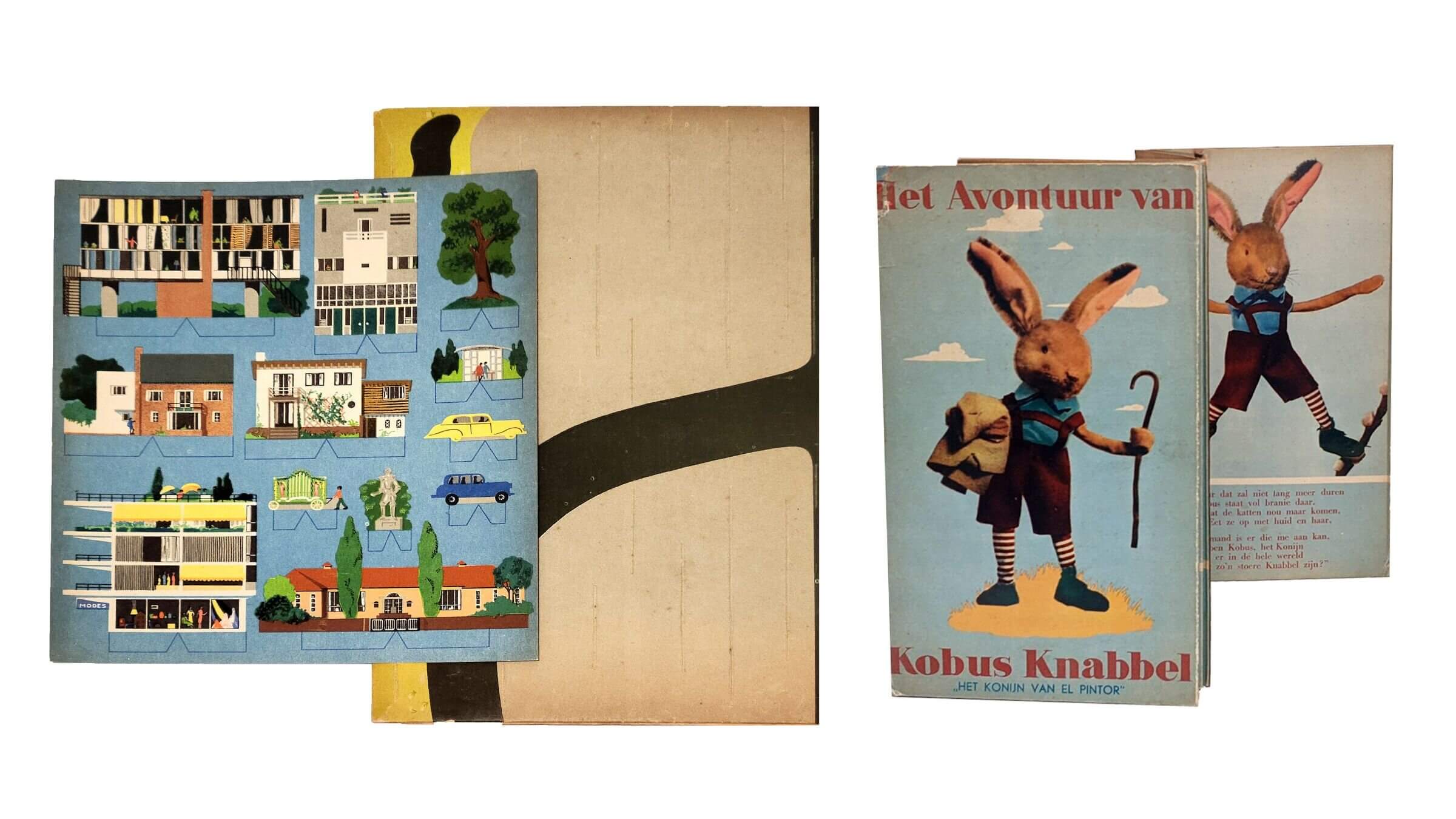

During the German occupation of the Netherlands, artists Jacob Kloot and Anna Galinka Ehrenfest published children’s books under the pseudonym El Pintor and funneled profits into the Dutch resistance. Courtesy of Ursus Books

A flying horseman. A zoo crawling with giraffes and crocodiles. A sailboat approaching a desert island swarming with strange plants and animals.

All of these sights must have been nearly unimaginable to children living under the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands during World War II. But a Jewish author and illustrator duo brought them to life through elaborate picture books they published anonymously under the pen name El Pintor. Distributed across the Netherlands and even sold in Germany, the books did more than just entertain young readers: They funded clandestine resistance efforts and supported Jews in hiding. Today, the few surviving copies are just beginning to garner the attention that collectors and rare book enthusiasts believe they deserve.

“You can’t look at these books and not say, ‘These are unbelievable,’” said Peter Kraus, owner of the rare bookseller Ursus Books, who is displaying a collection of 23 El Pintor books at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair this weekend.

Behind the pseudonym El Pintor were Jacob Kloot and Anna Galinka Ehrenfest, artists from the Netherlands and Estonia, respectively, who met while attending art school in the 1930s and became a couple shortly after. In 1940, Kloot founded a small publishing house called Corunda, which began publishing picture books that Galinka Ehrenfest conceptualized and illustrated. Blending old-fashioned whimsy with contemporary design (one picture book features a Bauhaus-style apartment building with a flourishing roof garden), El Pintor’s exuberantly colorful oeuvre includes titles like Animal Paradise, The Living Goat, and The Adventures of Kobus Nibble. (Kobus Nibble being an intrepid bunny in lederhosen.)

That same year Kloot founded Corunda, Germany invaded the Netherlands. In 1941, when the Nazi regime demanded that Jews surrender their businesses to non-Jews, Kloot entrusted Corunda to an acquaintance, continuing to use it as a publisher for El Pintor and devoting the profits to resistance activities. Proving popular within the Netherlands, some of the couple’s titles were even translated into German and sold within the Third Reich itself.

After years of evading capture and deportation, Kloot fell victim to the Nazis in 1943. When he and Galinka Ehrenfest attempted to buy a house, the Gestapo arrested him and sent him to Sobibor, where he was killed. Only a quarter of the Netherlands prewar Jewish population survived the Holocaust. Among them was Galinka Ehrenfest, who spent the rest of her life in the Netherlands. She never made another El Pintor book after her husband’s death.

In the decades since the Holocaust, little has been written about Kloot or Galinka Ehrenfest. Their books are remarkably rare given their relatively recent origins. In over 50 years as a rare bookseller, Kraus had encountered just a few El Pintor titles. “I knew from bitter experience that the books just aren’t around,” he said.

The rarity of El Pintor books is somewhat of a literary mystery. Their wartime origins, Kraus said, don’t justify the dearth of copies today — since the authorities apparently did not know that the artists behind El Pintor were Jewish, there was no reason for them to destroy the books. More likely, he said, the majority of El Pintor books met the usual fate of children’s books: destruction by enthusiastic children.

When a Dutch collector presented Kraus with 23 El Pintor books he’d spent 30 years acquiring, Kraus knew he was handling something important. Besides the unusual and tragic story behind their creation, Kraus said, the books stand out as artistic objects. While most children’s books series come in a unified size and format, the El Pintor books vary widely in their design, and no central character connects them. The collection includes pop-up books and a “flower market” book, in which small cards representing different plants can be nestled into different pots within the book. One book provides a basic explanation of color theory. Kloot and Galinka Ehrenfest seem to have wanted children to treat the books like toys and handle them as much as possible.

Kraus, who is selling the El Pintor titles on behalf of the Dutch collector, said that buyers often pass over children’s books. “They don’t yell, ‘Oh my god, I’m worth a ton of money,’” he said. But in recent years, institutions like Princeton and Yale have invested in children’s literature, and Kraus hoped the collection would land in a place where the public can access it.

Besides that, he hopes for a revival of interest in the story of El Pintor. “It would make a wonderful documentary or movie, because there’s an actual story there,” he said.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO