He survived the Holocaust to become the Polish Dan Rather and a chronicler of the Jewish experience

Documentarian Marian Marzynski’s films included ‘Shtetl’ and ‘A Jew Among the Germans’

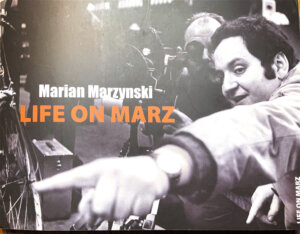

Marian Marzynski’s ‘Shtetl’ was shown on PBS’ ‘Frontline.’ Photo by PBS

If Marian Marzynski’s name was not known to the world at large, it certainly was to several subsets of people: viewers of PBS’ Frontline, documentary filmmakers and fans of those films, and anyone riveted by Holocaust survival stories and personal takes on Jewish identity in post-World War II Europe.

Marzynski, who lived in Newton, Massachusetts, and Miami Beach, Florida, with his wife of 60 years, Grazyna, an architect, died April 4, 2023, just eight days shy of his 86th birthday.

“Marian’s life is the stuff of legend,” said his friend, Boston ArtsFuse film critic and Suffolk University professor emeritus Gerald Peary, earlier this month. “His Jewish parents in Warsaw, soon Holocaust victims, released the 5-year-old, luckily not circumcised, into the streets and he was taken into an orphanage. Later, he became a TV star personality, a kind of Dan Rather of Poland, before emigrating to Denmark and then coming to the United States.”

Marian and his wife-to-be met in 1962 in the Polish port city of Gdynia. He was giving a lecture and she was attended. A spark was kindled. Did Grazyna have designs on Marian?

“Maybe,” she said, with a slight laugh, speaking on the phone from Brookline.

They married the following year, but left Poland in 1969 during what Grazyna calls “the antisemitic campaign.” While in Poland, he made films but struggled with Communist censorship. After coming to the United States, Marian took a position teaching film at Rhode Island School of Design where his students nicknamed him “Marz.”

Of his past, Marzynski wrote this in 2013 on PBS’s website: “I was five-years-old, spending my days in the attic of a woodworking shop my father was running in the ghetto when German soldiers were returning to their barracks. My parents carried me to bed in our tiny room above the shop. The German owner of the factory told my father that his work permit, temporarily protecting him from deportation, would no longer cover his family. My parents decided to smuggle me through the ghetto wall to the Christian side of Warsaw. My father and almost all our relatives, were killed. My mother and I were among a handful who managed to be saved outside the ghetto.”

“He probably didn’t remember much of his own experience,” Grazyna told me. As a young child, “he didn’t know why he was abandoned by his mother; he didn’t know about the war and Hitler. He wanted to learn more about himself and times.”

Peary says Marzynski’s film exhibited great ambivalence about Poland, “where the Nazis invaded and the history of Polish antisemitism. He would be looking through a lens of friendliness, but skepticism, about Poland’s relationship to the Jewish world.”

“I’m not Jewish, but I knew in Poland everybody was asking, ‘Is this person a Jew or not?’” said Grazyna. “I didn’t know anything, but when I met him, my world opened, and I embraced it.”

Peary considers Marzynski’s most important documentaries to be Shtetl! and A Jew Among the Germans.

” I find myself in the land of the enemy,” Marzynski says near the beginning of the latter film. “The German language alone strikes discord to my ears.” He believed one of his goals was undertaking a “journey to liberate my children from my Holocaust memories.”

“He goes back to the town where Jews used to live,” said Peary. “It’s always very personal, his view of Eastern Europe. Maybe most revolutionary was Marian’s extraordinarily intimate manner of conducting interviews, often standing in the frame squeezed next to the interview subject, making clear that he, Marian Marzynski, was part of the conversation. He’s walking around, finding out information, unlike the usual documentarian way which is you’re invisible. The ‘hidden documentarian’ is the normal way. He completely breaks this thing.”

While Marzynski injected himself into his films, Peary doesn’t think it was about ego. “He was a pretty warm guy and he exuded that extroversion and warmth and when he made the movies,” he said. Aside from PBS, Peary adds, Marzynski’s films “were shown exclusively at off-the-track Brandeis University in Waltham, where Marian was fiercely loyal to the support of the National Center for Jewish Film.”

“He was unique and extraordinary with an incredible sense of humor,” Grazyna “I was never bored with him. He always had ideas, sometimes crazy ideas, and he made me laugh all the time.”

Grazyna said that, over the past few years, her husband had been in an out of hospitals in the Boston and Miami areas and had been diagnosed with inoperable heart failure. He last went in the hospital March 3, but “by the end of March,” Grazyna said, “he signed the [DNR] papers. Marian was very particular: He said he didn’t want to be intubated. He was in hospice care at home with our daughter and son.”

The end, she said, was peaceful. “His head was so clear. He had been writing a series of blogs for a Polish paper in his hospital bed, dictating his last blog to us. The blog was his goodbye. He said ‘I did everything. I have nothing to do anymore and I just want to go.’”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO