How one artist’s work mattered even more than the subjects he photographed

Julius Shulman’s photography did a better job of selling buildings than the buildings themselves

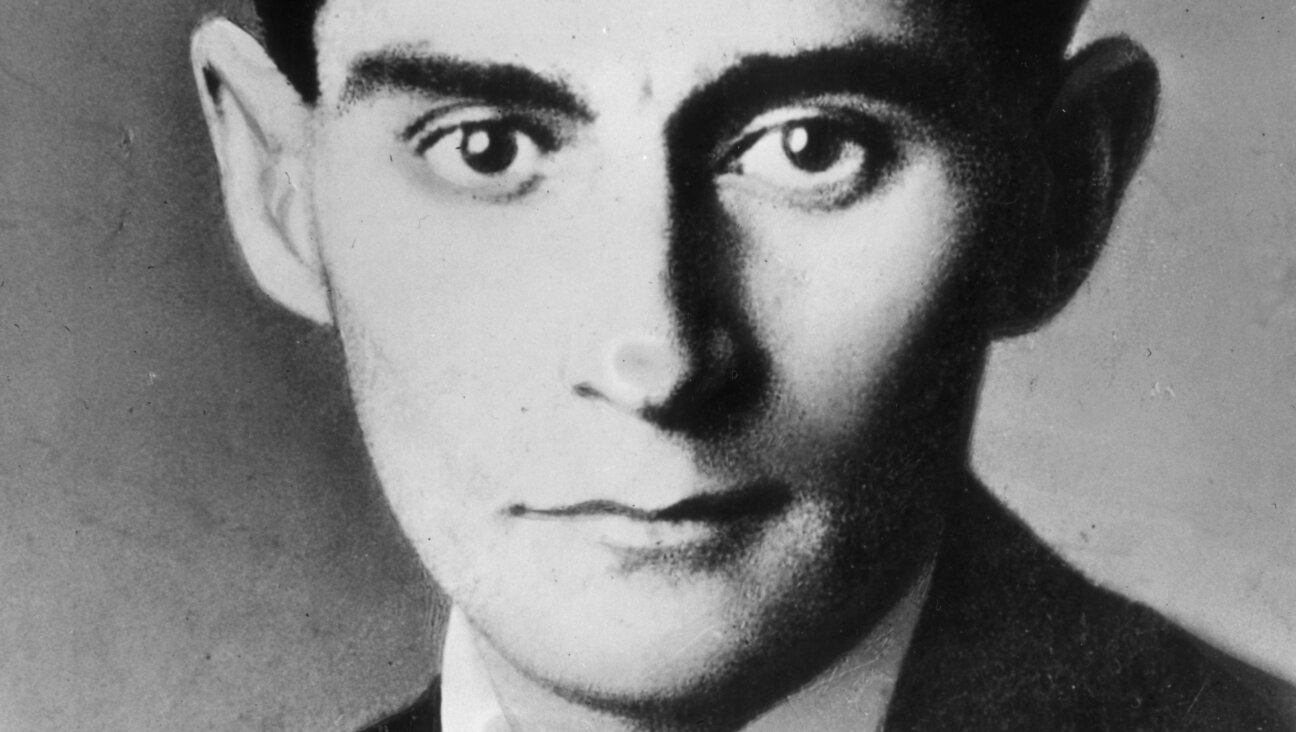

Julius Shulman’s photographs of Austrian Jewish architect Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House encapsulated 1940s Southern California. Photo by Julius Shulman/Courtesy of Getty Research Institute

A new edition of a lavish three-volume homage to American Jewish architectural photographer Julius Shulman serves as a reminder of how much modern West Coast Jewish architects relied on image makers to promote and preserve their work.

Shulman, who died in 2009 at age 98, came from a Brooklyn mercantile family of Russian Jewish origin. After childhood experience of antisemitism in Connecticut, where he was taunted by Polish American schoolmates, his family moved to California seeking commercial success.

Shulman would eventually find this success through the serendipitous exploitation of a natural instinct for the technical aspects of photography, and what he termed “merchandising” the sometimes stern ideology of émigré Jewish architects devoted to the anti-ornamental aesthetic of the Bauhaus.

Shulman exalted and humanized modern architectural ideas, making them simultaneously approachable and desirable. As historian Lawrence Culver put it, Shulman’s 1947 photograph of Austrian Jewish architect Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House was “emblematic” and an “iconic image for modernism” and for Southern California.

Critic Paul Goldberger added that Shulman was “incomparable” in conveying the “allure not only of Los Angeles but of modern architecture itself.” Indeed, Neutra and other architects were sometimes irked at exhibits, where Shulman’s work attracted more encomia than their own.

Never reticent about self-praise, Shulman informed an interviewer from the Archives of American Art in 1990: “I sell architecture better and more directly and more vividly than the architect does. The average architect is stupid. He doesn’t know how to sell. He’s not a merchandiser.”

Shulman was bemused by the resolve of stubborn Jewish designers to improve clients who had commissioned them. One example of the uncompromising, strictly disciplined creations of Austrian Jewish designer Rudolph Schindler was a three-legged chair that required any sitter to maintain ideal posture or risk toppling over.

Unreceptive to such didactic élan, when Shulman commissioned a house design for his own use from Sephardic Jewish architect Raphael Soriano, a native of Greece, it included some distinctly uncomfortable furniture that looked good on the drawing board. Shulman would eventually replace it, much to Soriano’s annoyance.

Another example of Shulman sweetening the relentless idealism of progressive Jewish architects was to accentuate the placement of their buildings in nature. Shulman was usually called in to document new houses before landscapers had arrived. So he would enlist staff, or on occasion his employers Mr. and Mrs. Neutra, to hold up tree branches to appear deceptively in the corners of pictures, as if gardens had already been planted.

On at least one occasion, when azaleas were missing from a Pasadena garden, Shulman and a colleague replaced them with crumpled Kleenex. Seen from a distance in black and white reproduction, the tissues could not be distinguished from real flora.

Accentuating openness to the outdoors was more than a design statement about the balmy California climate. In the 1930s and 1940s, when European Jews were being imprisoned and murdered, the sheer transparency of American buildings featuring glass walls harmonizing with the environment was the opposite of what mishpocheh in the Old Country were experiencing.

Shulman felt a corresponding sense of freedom in 1959, when he was invited on a 10-day photographic tour of Israel. There, with modernist Israeli architect Dov Karmi as guide, he recognized Bauhaus inspiration in architectural designs, as in Southern California buildings created by Jews. Again, Shulman captured nature in a way that softened inexorable angles of edifices.

To photograph trees, shrubs, and other greenery surrounding buildings in Israel, Shulman waited until quasi-theatrical natural lighting added dramatic impact. One such visual was of the Baron Edmond de Rothschild Memorial in Ramat Hanadiv, a northern Israel park and garden designed by Uriel Schiller, an architect born in Slovakia.

Shulman posed scientists on exterior balconies of Haifa’s Technion — Israel Institute of Technology as evidence of intellectual fervor, in tribute to work by architects Benjamin Idelson and Arieh Sharon.

Just as in California, where he staged photos by asking female assistants to loll around a backyard pool as if they were enjoying the high life, Shulman indulged his unsurpassed eye for composition by asking Israeli families, including small children, to pose near houses.

The results reminded Jewish viewers of how ideally, architecture serves humanity. After the devastation of World War II, life continued for survivors in the Jewish state.

The interdependency of the work by Jewish architects and Shulman’s visual salesmanship was especially clear when buildings by Neutra, Soriano, and others were later demolished, some as recently as two decades ago. Of Soriano’s 50-or-so buildings, only a dozen survive today, with few in their original condition.

Neutra’s Cyclorama Building in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a modernist concrete and glass masterpiece, was destroyed by the National Park Service in 2013. With these artistic treasures no longer extant as evidence of 20th-century Jewish creativity, Shulman’s efforts were all the more precious as proof of past achievements.

Documenting further evidence of Jewish architecture in the service of humanity were Shulman’s photographs of a 1948 social housing project for low-income residents on Avenel Street, Los Angeles. It was conceptualized by Gregory Ain, an American Jewish disciple of Schindler and Neutra.

As urban historian Daniel Hurewitz explained, the project was an effort to “refine and dignify the low-cost house.” Shulman focused on children playing harmoniously. He often recalled his own upbringing in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, once a predominantly Jewish neighborhood which also welcomed a diverse population of emigrants who coexisted without the anti-Jewish rhetoric he had heard in Connecticut.

The humble peaceable kingdom on Avenel Street was somewhat unusual subject matter for Shulman. More often he focused on luxury avant-garde domiciles of prosperous clients like American Jewish film director Josef von Sternberg, who had demanded that Neutra design a moat outside his house. Sternberg’s steel and glass edifice was demolished in 1972, but Shulman’s photos survive.

Shulman was motivated by delight in visuals, rather than friendships with architects, most of whom, he told the Archives of American Art, are “good designers, but there are not many who are great human beings. They’re too busy making money or too busy getting involved in the competition, and it’s a tough business.”

In later years, Shulman decried such American Jewish postmodernist architects as Frank Gehry as mere surface decorators, compared to creators of his youth. In old age, a prodigious memory permitted him to educate new generations of researchers and recall the haftarah, the section from the Prophets read on Shabbat at the conclusion of the weekly Torah reading, which he had learned for his bar mitzvah eight decades before.

Some architects whom he had promoted went out of fashion, like Soriano, who went without a commission for 30 years, subsisting instead on academic jobs. By contrast, Shulman’s legacy only grew in stature with the years. In 2005, Shulman sold his archive of over 260,000 negatives, prints and transparencies to the Getty Research Institute, where it has been digitized for the admiration and edification of those who kvell at great buildings created by Jews and splendid representations of them.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO