‘I am the map, the quilt, and tablecloth of those who have come before me’

‘HaMapah,’ a new installation at Fentster, traces dancer Adam McKinney’s multifaceted ancestry

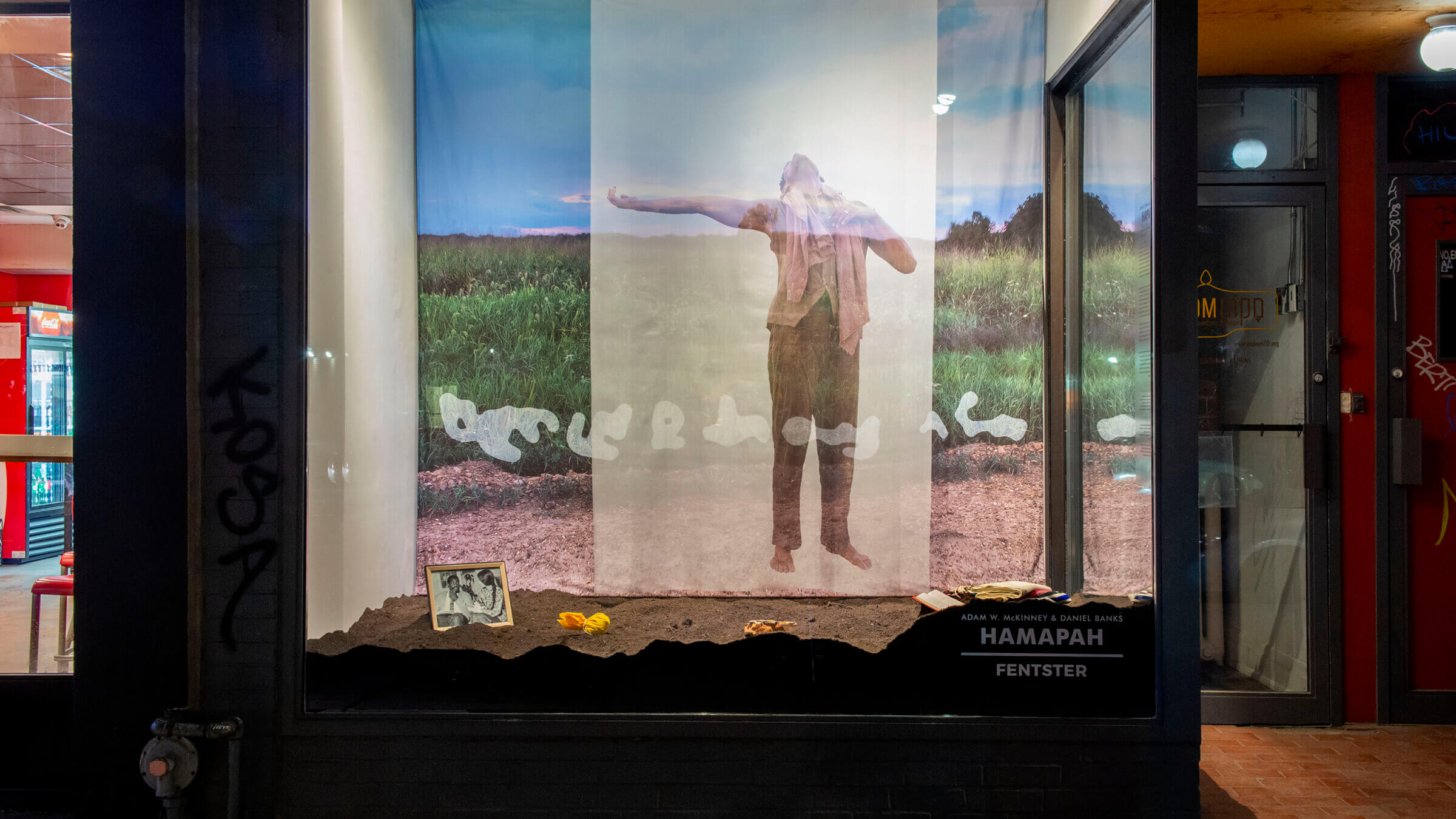

“HaMapah” by Adam McKinney and Daniel Banks at Fenster. Photo by Fentster

The art gallery Fentster operates out of a single shop window in downtown Toronto. Yet somehow, the tiny space fit an entire ton of dirt, shipped in for its newest installation.

“HaMapah” is an artistic project from former Alvin Ailey dancer Adam McKinney, using dance to trace and explore his layered Jewish, African American and Native American heritage. For the project, McKinney, who was just named the new artistic director of the Pittsburgh Ballet Theater, journeyed to places deeply tied to his ancestry — a synagogue in Poland, a farm in Arkansas where his father’s family was enslaved, the town in Benin where his family traces their roots. The project has been a dance performance, a multimedia project and a film, directed by McKinney’s husband, Daniel Banks.

Bringing that sense of place to Fentster’s space took some innovative thinking. Hence the dirt, piled in waves against the glass, rooting viewers the second they walk up. An image of McKinney dancing on the Arkansas farm, arms thrown up, is printed on a diaphanous piece of fabric, while objects arrayed in a semicircle through the dirt carry pieces of McKinney’s identity — a rainbow tallis McKinney’s parents gave him, a brick from the Polish synagogue, a Native American prayer tie.

Often, Fentster’s installations speak to Jewish Canada; past projects have referenced the overlapping histories of Chinese and Jewish immigrants, for example, or the Yiddish deli culture of Toronto. Which might make “HaMapah” seem like a strange choice for the gallery — after all, the project is about a genealogical geography that does not include Canada.

But for curator Evelyn Tauben, it feels particularly timely to bring “HaMapah” to the Canadian Jewish community, where she said, despite Toronto’s diversity, the conversation around race and identity is still “nascent.”

“Because of his particular family and upbringing, in some ways, he’s done more reflecting, reckoning and creating around this mixed heritage and identity,” she said of McKinney. “As we’re trying to make space for that conversation and grow it and support Jews of Color, I think there’s something to be said for cross-pollinating with artists and community members in the U.S. who may have been in that discourse for a bit longer.”

Every aspect of “HaMapah,” including its name — a reference to McKinney’s ancestor, Moshe Isserles, who wrote an influential Jewish legal commentary by the same name — is a heavily weighted artifact. And each piece engages with the concept of disparate yet merged identities, serving to bring the pieces together.

McKinney and Banks are now busy moving to Pittsburgh. But between the boxes and the chaos, they found time to answer a few questions about “HaMapah.” This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Talk me through the different objects in the installation — what is the significance of each one? How did you pick them?

Daniel Banks: The objects represent loci of Adam’s multiple and intersecting identities and a declaration of self and belonging. Each represents symbols of resilience in a world that so often attempts to dissect identity into percentages and fractions.

As he says in the full production of HaMapah/The Map, “I am the map, the quilt, and tablecloth of those who have come before me.”

How does this installation, since it is obviously static, tie into the dance aspect? How did the constraints of Fentster impact or change the project?

Banks: We were introduced to the technique of printing on fabric by the Fentster team — installation consultant Daniel Toretsky and director and curator Evelyn Tauben. And we felt that Adam’s body position in the photograph transferred onto the fabric would in itself convey movement. We chose the semi-circle for the identity artifacts because that also has a sense of energetic movement, especially encircling Adam’s image.

What was most important to us was the sense of liberation and freedom that the image conveys, surrounded by family and personal history as embodied by the location and the rich storied artifacts.

How does dance, specifically, help tell or embody the interwoven stories of place, identity and multiple oppressions that are part of your history?

Adam McKinney: I believe that our bodies are endemically connected to land and place. The dances our bodies dance are connected to the places from where we come. My identities cannot be separated from my body; in many ways, my body is my identities.

I also believe that not only do our bodies hold history, but land holds history. And not only do our bodies have the capacity to hold onto trauma, but so, too, does land. Dance is a powerful tool to release our associations with traumatic experiences. As an artist, my interest is to look back and go back to sites (including my body as a site) to feel and heal as acts of return, repentance, and forgiveness.

What was it like getting to be, physically, at the sites of so many pieces of heritage? How did the physicality of these places impact your sense of self/identity?

McKinney: Often my experience of being mixed-heritage is the expectation that I am to fracture or divide myself into a smaller self to fit the molds historically created to oppress some and privilege some. Part of the impetus to create HaMapah/The Map was to defy my own answer to the question that I often receive — “How are you Jewish?” — which was: “I’m fine, Jewish. How are you, Jewish?”

Traveling to the sites of my ancestors to film HaMapah/The Map Dance with Daniel and cinematographer Laura Bustillos Jáquez — Ouidah, Benin; Siedlanka, Poland; Harlowton and Lewistown, Montana; Forrest City, Arkansas; St. Louis, Missouri; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin — was, in many ways, a homecoming. Not only was I able to locate homes and farms and synagogues and water, but I was able to reconnect with family members after more than 75 years of separation. The power of dance provides us with pathways to find others and also ourselves.

What do you hope to communicate to audiences of the film and installation? What are the most important takeaways or resonances for specifically Jewish audiences?

Banks: The installation is an outgrowth of the stage production and the film HaMapah/The Map. And the intention of those works is to model the liberation that one can find in owning all the parts of one’s identity — as Adam conveys, “Whole and full and all and not half anything.”

The technology of “race,” as invented by 18th- and 19th-century taxonomists and scientists trying to prove which peoples were more rational, and therefore more human, than others, has left humanity in a state of reducing and dissecting the inherent complexity of identity that we all have. Each one of us contains multitudes that no census boxes will ever capture.

Given all this, for Jewish readers the resonance will be clear. We know where our history began. To ask a person “What they are,” or to be told, as I have been, “You can’t be Jewish,” is mere proof of the ways that colonial thinking has infected our religion and people. Given our origins, how could there not be members of k’lal Yisroel with all tones of skin and facial features? We must remember from whence we came and what we looked like at that time. Perhaps if we acknowledge this more often, we will all feel more deeply how we belong with and to one another.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO