Slave and victim of the Nazi regime — the complicated legacy of Bruno Schulz

Benjamin Balint delves into the history of the ‘virtuoso of language and image’ who was murdered on ‘Black Thursday’

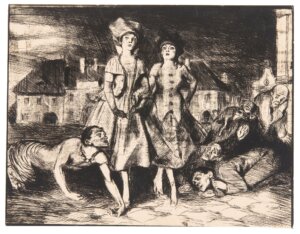

Bruno Schulz’s ‘A Meeting. Jewish Youth and Two Women in the Town Alley’ Courtesy of W.W. Norton

Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History

By Benjamin Balint

W.W. Norton & Company, 288 pages, $30

The endlessly complex question of cultural ownership animated Benjamin Balint’s Kafka’s Last Trial, winner of the 2020 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. That book detailed a multigenerational struggle over papers that Kafka had tasked his friend and executor, Max Brod, with destroying. Brod instead preserved them, and a legal quagmire ensued.

The dislocations of World War II and the Holocaust, involving looting, forced sales and other forms of dispossession, have given the issue of cultural ownership particular salience. Balint mines this potentially rich historical and philosophical vein in his latest book, on the writer and artist Bruno Schulz (1892-1942).

A gifted but lesser known figure than Kafka, Schulz, too, was born into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the empire dissolved, and Schulz’s native Galicia became part of Poland, so did he. He wrote in Polish, beautifully enough to wow his literary contemporaries. He also created images of grotesque realism in the tradition of Goya. Jewish by heritage, he at one point renounced his Judaism to affiance himself to a Catholic woman. But after the Nazi invasion, that wasn’t enough to save him.

As Balint puts it, “Schulz was born an Austrian, lived as a Pole, and died a Jew.”

Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History is a genre mash-up — part biography, part literary and art criticism, and part cultural inquiry. The narrative is framed by the question of whether Israel’s Yad Vashem was right to commandeer the fairy-tale murals that Schulz painted at the Polish villa of his SS tormentor and protector, Felix Landau.

Balint, enamored of Schulz arcana, straddles the line between the popular and the academic. His tendency to tip toward the latter makes Bruno Schulz a smart book, but not an entirely satisfying one.

His shifting focus doesn’t help. Balint lurches from Schulz’s literary and artistic pursuits to his tortured romantic relationships to the vividly depicted brutality of his Nazi patron. (Because Landau kept a journal, his personality bursts from the page.) Balint also covers Schulz’s cultural afterlife and, in exhaustive detail, the debate over the villa murals.

Balint offers images of Schulz’s art and quotations from his writing, which included two short-story collections. He lauds Schulz as a “virtuoso of language and image,” whose prose “may very well be the most beautiful ever written in Polish.” He also notes his influence on writers as diverse as Philip Roth and the Polish Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz.

The debate over where Schulz’s murals belong is complicated, Balint suggests, by the fact that they were created under compulsion. It’s complicated, period. But especially for those of us unfamiliar with Schulz’s artistic legacy, the mural controversy is overshadowed by the larger horrors of the period, including Schulz’s own murder.

Balint begins his narrative with a visit to Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum and memorial, to see the restored murals.

“Long before the war,” he writes, “Schulz had created unnerving masochistic scenes, depictions of men groveling at women’s feet. These caught the eye of the sadistic SS officer with a Jewish stepfather who would serve as Schulz’s ‘guardian devil’ and would determine Schulz’s fate. In this uneasy alliance, Schulz’s art became the currency with which he bought life.”

Balint muses that the art Schulz made “with the free play of his imagination is servility made visible,” while the murals “created under the most coercive conditions” depicted “unflinching freedom.” The murals were rediscovered in 2001 by two German documentarians, whose unfulfilled dream was to make the villa into a museum. “The competing claims that arose so long after Schulz’s death are like the ends of separate strings that trace their origins back into Schulz’s life,” Balint writes, in slightly unwieldy prose.

Flashing back to that life, Balint describes Schulz as imaginatively anchored in his Polish hometown of Drohobycz (now part of Ukraine), with its mix of sometimes amicable, sometimes warring Poles, Jews and Ukrainians. After spending much of World War I in Vienna, Schulz returned in August 1918, on the eve of “ethnic riots” in Ukraine and Poland that killed an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 Jews.

By 1920, Schulz was in Warsaw, studying at the School of Fine Arts and, according to one account, molesting one of his models. In 1924, he became an arts and crafts teacher in Drohobycz but “chafed at the stultification of his tasks.” Nevertheless, Balint reports, his students loved him for his storytelling gifts. Meanwhile, his own art displayed what Balint calls a “tawdry preoccupation with servility and subservience.”

Schulz liked women, but never had much luck with them. Or maybe he just had no romantic stamina. He proposed to the avant-garde poet Debora Vogel in 1931 but she married another man later that year. An important Polish editor, Zofia Nalkowska, declared his first short-story collection, Cinnamon Shops, “the most sensational discovery in our literature!” They duly became lovers. Next came a young teacher, Józefina Szelińska, for whom he announced his “formal withdrawal from the Jewish community.” Their engagement was broken in 1937, and neither of the two ever married.

The Soviets occupied Drohobycz at the start of World War II, and Schulz was forced to paint propaganda posters. The Soviet retreat was followed by vengeful Ukrainian pogroms and the Nazi occupation. We know the horrors that happened next: mass shootings, ghetto confinement, starvation, deportations to the Belzec death camp.

Schulz survived for a while because his path had somehow crossed Landau’s. “With Landau,” Balint writes, perhaps too cleverly, “the Nazi art of power met Schulz’s power of art.” Landau made Schulz a “necessary Jew,” an artistic slave who painted on demand. At the same time, Landau was murdering other Jews. “Isn’t it strange: you love battle and then have to shoot defenseless people,” he complained in his journal.

Schulz’s friends devised various plans to save him, but he waited too long to flee. He was killed on “Black Thursday,” a day of random Nazi massacres. It remains unclear exactly how, or by whom. Balint offers five different accounts.

At first forgotten, Schulz was later venerated in the context of Poland’s own incomplete accounting of its role in the Holocaust. Balint details the rediscovery of his work, which has included exhibitions, film and stage adaptations, translations, conferences — and the wrangling over the murals.

Still missing, Balint says, is the manuscript of Schulz’s novel, Messiah, which “exists only as a metaphor of loss, as proof of the absence of redemption.” As for both the murals and Schulz’s literary legacy, he writes, they remain “a palimpsest of competing myths.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO