A Jewish painter, perhaps, but undeniably a spiritually transcendent one

Standing before the paintings of Helen Frankenthaler, it’s hard not to feel a sense of awakening

In her painting “Vespers,” Frankenthaler has dragged a rake, suggesting the presence of fingers almost as if from the hand of God. Photo by Rob McKeever/Courtesy Gagosian

Drawing within Nature: Paintings from the 1990s, currently at the Gagosian Gallery, marks the first New York exhibition since 2014 of the work of the abstract artist Helen Frankenthaler, who died in 2011 at the age of 83.

According to Gagosian director Jason Ysenburg, these works show “a sense of freedom and a sense of experimentation” of an artist in her prime, painting confidently while trying new things. “You have an artist who is at the top of her game but still wants to find ways to be an innovator and I think that’s the key to seeing these works,” said Ysenburg. “It’s very much a period in which she is reflecting on her career.”

Like her earlier works, most of these were painted on the floor, though, according to Ysenburg, “the application of the paint is different from earlier works in that she is covering the entire canvas. She’s not choosing where to pour the paint.”

These works also show Frankenthaler’s progression towards the greater use of texture. In her earlier “soak-stain” paintings, in which she saturated the unprimed canvas with color, such as in her first breakthrough work, 1952’s “Mountains and the Sea,” she poured the paint so that it stained through the unprimed canvas. By the 1980s, one began to see clumps of paint in her work. In most of this exhibit’s paintings, the paint sits on the canvas’ surface. In several, she has even added silica to the paint in order to achieve added texture.

Here, in the 1990 painting “Hot Ice,” which Ysenburg calls a “master class in how to make different volumes of paint work together on one canvas,” the paint consists of many different thicknesses and liquidities. In one spot there’s a clear imprint of a boot in the paint; in other places, the imprint becomes less clear, suggesting ice disintegrating or melting.

In works like this one, Frankenthaler seems to be calling attention to the act of painting, to the presence of the artist’s hand. This is also true of other works in the exhibition where the artist uses a rake, dragging it through the paint to create tracks or curved lines, calling attention to her process.

While Frankenthaler was born to Jewish parents and raised in a Jewish home in Manhattan, not much has been written about how her Jewishness influenced her work.

“I don’t know whether there is a strong sense of spirituality in her works,” Ysenburg told me.

I asked Ysenburg about Mark Rothko, born Marcus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz, whose abstract paintings create a spiritual feeling in viewers, so much so that his paintings fill a chapel. He told me that he sees Frankenthaler’s paintings as “more sensational than contemplative,” and that he sees Frankenthaler as “translating an experience, a physical experience of being in nature.”

In his book Fierce Poise, Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York, Alexander Nemerov wrote that critic Clement Greenberg, with whom Frankenthaler had a serious relationship during the ’50s, said that Innerlichkeit, or inwardness, was “the real task for the individual Jew in the West,” and it was perhaps this quality, according to Nemerov, that Greenberg saw in Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea and her art of that period. Her earlier color field paintings reflect this quality of quietly looking within.

Yet the spirituality in the works seen here seems intentional, even blatant. One, which features different shades of blue and the whites of clouds, is titled “Vespers,” referring to an evening prayer in church. At the top right corner, Frankenthaler has dragged a rake, suggesting the presence of fingers almost as if from the hand of God.

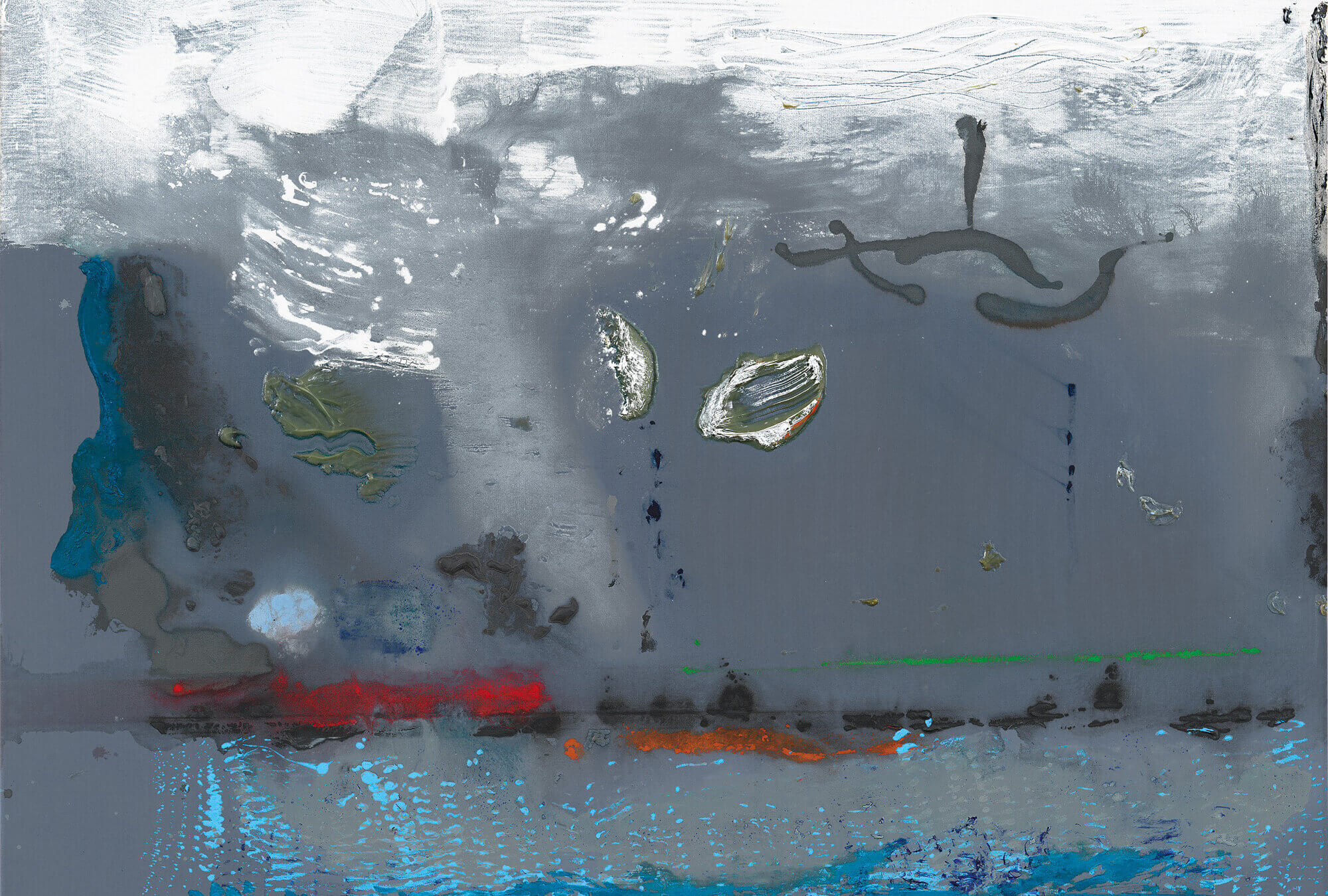

Ysenburg calls the 1992 painting “Magnet” the “most provocative” in the exhibition.

“I feel it’s about the elements. It’s a representation of some kind of storm,” he said. “The physical nature of the way it’s painted. The raking and the dragging and the layering of the painting; it’s the most alive work in the show.”

True to its title, “Magnet” seems to pull you towards it, making you want to stand close. I would argue that the reason it feels so alive is because of Frankenthaler’s wild and original juxtaposition of colors, of bold purple and turquoise, yellow and umber, the way light seems to emanate from within it, and the way she simultaneously calls attention to the artist’s hand — through the clumps of lavender paint and the various rake lines. Standing before it, it’s hard not to experience a sense of awakening and transcendence.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO