Why ‘pi’ is Darren Aronofsky’s best — and most Jewish — film

Now showing in IMAX, the film was inspired by the director’s trip to Israel

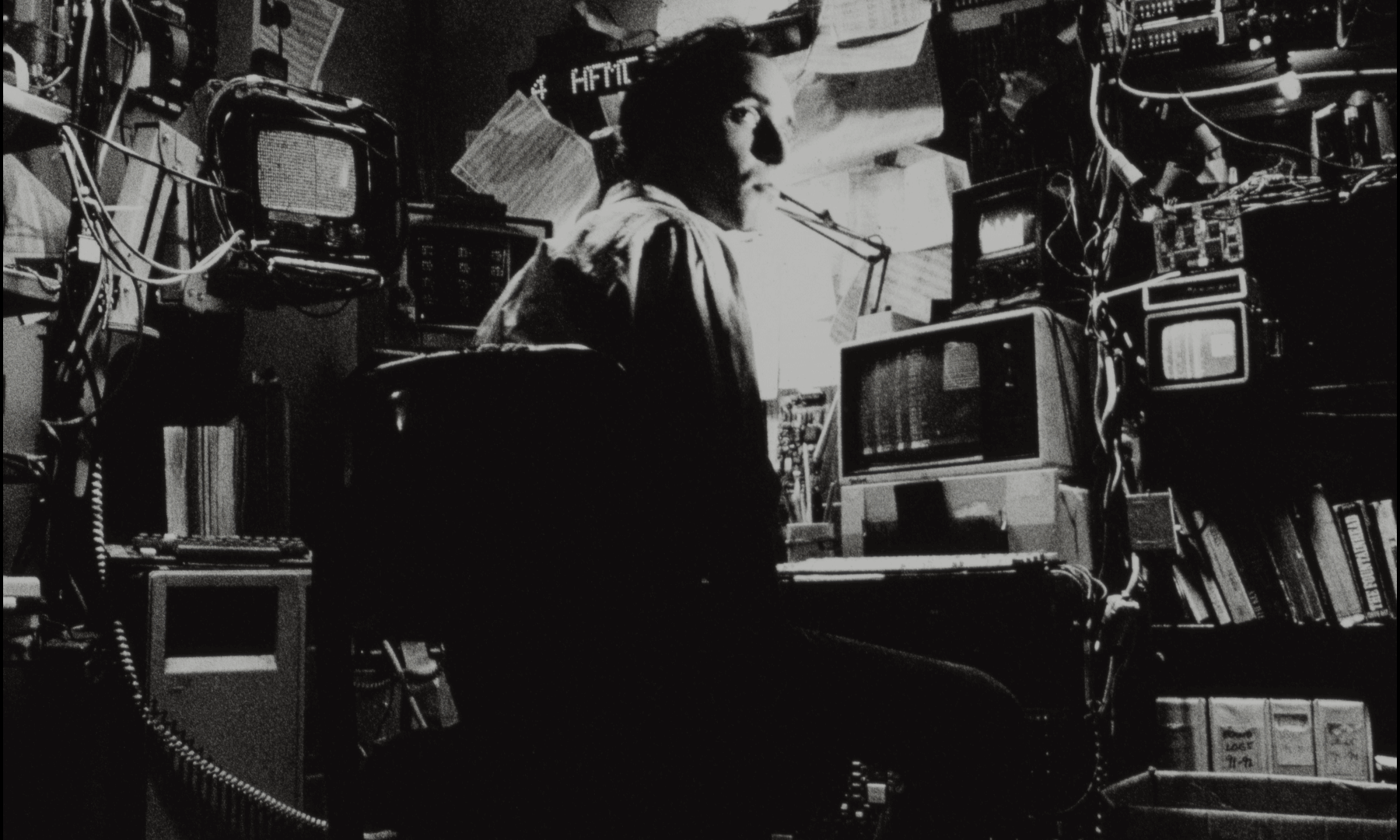

Sean Gullette plays an obsessive mathematician in Aronofsky’s pi Courtesy of A24

Pi, the film if not the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, began life near the Kotel in Jerusalem — by way of a plastic factory.

When he was 18, Darren Aronofsky was backpacking through Israel. He dreamed of picking avocados, but instead found work sprinting between assembly lines as Sabra workers yelled at him to pick up the pace.

“It was a nightmare,” he told film journalist Andrea Chase, shortly after his first feature, pi, won the award for best director at 1998’s Sundance Film Festival. “I ran away after two days.”

He wound up at the Western Wall, where Haredi Jews introduced him to mysticism, hoping to return him to the fold “away from Satan.”

“For me it didn’t quite work, because the devil has some nice toys,” Aronofsky said. “I did come away with some nice stories and some good ideas. That was the seed for a lot of the Kabbalah stuff in the film.”

Pi, which was made for $60,000 on a notoriously finicky filmstock called black-and-white reversal, will debut in a 25th anniversary IMAX print on Pi Day. It’s a curious transfer given the original film’s 16mm format, but the oversized presentation may well amplify the film’s strengths — an overwhelming paranoiac soundscape, a sense of the almighty’s enormity and, above all, our inability to grasp the patterns of the world without losing our sanity.

The film follows Max Cohen (Sean Gullette), a mathematician studying the stock exchange for hints of a unifying numerical order. Max is unwell, self-medicating a litany of vague mental disorders with a battery of drugs and therapies. When Max’s computer spits out a mysterious 216-digit number, his mentor, Sol (Mark Margolis, later to star as menacing bell-ringer Hector Salamanca in Breaking Bad), who had a stroke calculating pi, warns him not to chase it.

Just as the young Aronofsky abandoned the grind of the plastic factory for the Zohar, Max ditches the financial pages after Lenny (Ben Shenkman), a Haredi Jew, walks him through Gematria (“Torah math”) at a diner counter.

As Clint Mansell’s soundtrack screeches like an old dial-up modem, and Max accrues debilitating cluster headaches, we learn that the 216-digit number is the lost name of God. Uttered in the Holy of Holies beyond the Kotel, Lenny’s kabbalist friends insist that it will usher in the messianic age.

Released a year before The Matrix, and anticipating its trademarks in a grubbier fashion, pi is pop mathematics imbued with a Jewishness Aronofsky would revisit intermittently with mixed results. Noah, a flawed but never uninteresting retelling of the deluge, taps inspiration from cryptic mentions of nephilim in Genesis 6 and the non-canonical Book of Enoch. 2017’s mother! was influenced by an alternate translation of the first line of Bereshit (“in a beginning”). But pi remains Aronofsky’s strongest realization of a Jewish theme.

Max spirals, fending off a Wall Street executive and a minyan of believers who want him to forfeit his divine epiphany. A cascade of graphs, ticker symbols, lines of numbers and the churn of obsolete machines assail the senses. The viewer feels like Max, circling a terminal error from too much knowledge.

Through this flood of information, Aronofsky delivers the concept of an endless divine, intolerable in its magnitude and buzzing with the nervy atmosphere of Lower Manhattan. After touching the void, Max finds happiness in a leaf wavering in the wind — one small spark of God’s creation. It is only by shattering himself, a violent self-creation that mirrors the Shevirat haKeilim, the breaking of the vessels in the making of our reality, that Max can appreciate a simpler world.

In making the film Aronofsky consulted with Hasidic kabbalists, “the guys who are the direct descendents of the people who summoned golems to defend the Jews from the Cossacks.” Yet his Kabbalah lesson is brimming with the “devil’s nice toys.” The film’s mysticism supposedly invents nothing, but has no pretenses as a holy work.

In 1998, when asked if the film is about math, Aronofsky demurred. “It’s about all that cool math theory that you hear about at cocktail parties, you know, chaos theory and about connecting the universe and looking for God through math that everyone always finds so interesting and wants to hear more about,” he said.

He was equally coy when speaking of it in religious terms, offering that the film is “anti-religion and pro-spirituality.”

Certainly the film chafes at systems: the stock market, organized religion and the rhythm of urban life. But there is no denying that Aronofsky’s search for meaning is a Jewish one. Running from the assembly line to the Western Wall, and back to his native New York, he gave us a film like nothing else.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO