A Jew warned her that she might have to escape America someday

Human rights lawyer Sofia Ali-Kahn stresses the need for Jewish-Muslim solidarity in the face of rising white Christian authoritarianism

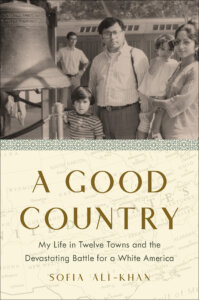

Sofia Ali-Kahn is the author of A Good Country: My Life in Twelve Towns and the Devastating Battle for A White America Courtesy of Penguin Random House

The Pakistani American human rights lawyer Sofia Ali-Khan first surfaced as an important national voice through a viral Facebook post she wrote in 2015. It was becoming clear that Donald Trump’s rhetoric of hate — toward immigrants, toward Black Americans and especially toward Muslims — was helping his campaign, not hurting it. Ali-Khan, herself a practicing Muslim, responded to the threat with what she titled “An open letter to our allies.”

“I’m writing because it’s gotten just this bad,” Ali-Khan began, and then went on to suggest ways to support our neighbors in an era of political hate speech and threats of anti-Muslim legislation. She told of a Jewish escapee from Nazi Germany she’d met decades earlier, a thoughtful mentor who’d listened to her life story, then issued a warning she couldn’t understand at the time: Make sure your passport is in order.

In 2017, the same year that the Trump administration implemented the now infamous executive order 13769 — better known as the “Muslim ban” — Ali-Khan moved with her husband and children to Canada. (The ban excluded travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries for 90 days, among other things; the restrictions faced legal challenges and were eventually terminated.)

In that same year she also began work on her hybrid memoir/history, a heartbroken farewell to the place she’d thought was home, In A Good Country: My Life in Twelve Towns and the Devastating Battle for A White America, Ali-Kahn weaves personal memories with exhaustively researched history, excavating the ghosts from America’s past and exploring how they haunted her present. From the forced repatriation to Liberia of formerly enslaved Black people in Princeton, New Jersey, to the stolen lands of the Lenape in Pennsylvania, to the Native and Black rebellions in Florida and beyond, each chapter reveals — with an activist’s outrage and a lawyer’s relentless precision — the ways in which the origin myths of the United States as a pluralistic project collapse under scrutiny.

Today, hate speech and the violence it inspires have continued to rise,. and many Americans, including but not limited to Black Americans, trans people , and yes, Jews, are asking themselves questions very similar to those that drove Ali-Khan away five years ago. Am I safe here? What about my children? If we left, where could we go? I spoke with Ali-Khan about her book, her faith, and the urgent need for Muslim-Jewish solidarity, both in the United States and as a response to the rise of white Christian global authoritarianism.

In both that first post seven years ago and in A Good Country, you write about the Jew who first warned you of your potential vulnerability in the United States. What was your response?

At the time I wasn’t sure what he was about — I was young, I was going to a hippie liberal arts college, which was fairly small, fairly white. I hadn’t developed a cohesive identity for myself yet.

But he said it with a sincerity that stuck with me. I didn’t really understand how it could ever apply to me, until many years later after the fall of the Twin Towers, when there was a major wave of anti-Muslim violence and persecution.

And this was neither the first nor the last time you felt a kind of connection with Jews in your life.

Completely. You can see it in the book — I find myself in high school, and then again, in college, in the margins. Whenever I’m in the social or political margins, I find myself surrounded by Jewish people. And then as a young adult, an activist, and as a Legal Aid lawyer, those spaces are also disproportionately Jewish. That was a great blessing for me, because those were folks that could relate to much of my experience.

So it was a personal connection for you from the start?

Yes, but beyond that, there’s a historical and political context of white and Christian supremacy, in which our two groups are frequently marginalized in very similar ways. Although we have different particulars, what we actually experienced on the ground — the microaggressions, the exclusion, the battles to exist and be named in public spaces — those are all very similar, right?

And we share a specific kind of racialization, where the line between racial identity and religious identity is muddied whenever it is expedient, so that we find ourselves ‘othered’ at different points in the history of this country.

In A Good Country, you write frequently about that “muddiness.” Depending on what you’re wearing, on who you’re with, on what you say, you’ve landed on different sides of the whiteness line at different points in your life.

It’s sometimes contingent on how tan I’ve gotten, whether I’m wearing a hijab, whether I’m with my dark-skinned Muslim husband or not, whether I’m with my parents or not, whether one of them speaks.

The interesting thing for me about the racialization of Muslims as Muslims in America, is that we are incredibly diverse. We speak virtually every language on the planet, and practice every culture on the planet. In the U.S. about 30% or so of us are Black. There is a substantial number of African immigrants, and an enormous number of Asian immigrants. And so the idea that we would be racialized as a category together, really is bizarre.

How do you navigate between that sense of shared experience of racialization that Jews and Muslims in the U.S. both encounter, and your strong solidarity with Palestinians in the Middle East?

The same way I navigate everything else: a clear commitment to human rights for everyone, no matter what. Respect for everyone, no matter what. Telling the truth, no matter what. Those three things are the guideposts, even if they make for uncomfortable conversations.

You have been involved with several interfaith organizations dedicated to facing these conversations. Has Israel/Palestine been one of the points of discomfort?

Yes. But this is where the importance of honesty comes in. We have Truth and Reconciliation Commissions because those two things go together. If you don’t tell the truth about a problem, there’s no chance for reconciliation.

I have been told by Black friends, “it’s not my responsibility to argue with racists, about history, it’s the responsibility of white people to call out their own.” Does it put you in a hard position — as a Muslim, to contend with that, to play that role with Jewish people who have troubling positions about Islam?

I’m going to answer your question with a question: What do you imagine is being said that is difficult to contend with?

Well, growing up, I heard all the time, even from members of my own family, who would for the most part certainly describe themselves as liberal: “Islam is a violent religion.” “They are fanatics.” “They have no interest in peace, they want to destroy us.”

Here’s the thing: I’ve heard all of those things in non-Jewish contexts as well — and out of the mouths of non-Jews. Anti-Muslim bigotry is everywhere, and it’s difficult to confront no matter where it comes from.

If there is exceptional pain — in the context of the Muslim-Jewish relationship here in the U.S., it’s because colonial attitudes and bigoted language are so antithetical to the other broader solidarity I’ve felt with Jewish people, almost unilaterally, whenever I’ve encountered them in my personal life. For me — and perhaps for other Muslims as well — one anticipates a certain empathy because both groups have faced so many similar challenges in Western society.

When that solidarity and empathy isn’t there, it hurts.

What about the specific argument that Muslims are especially given to “terrorism” and violence?

I just spent five years researching the history of European colonization in the Americas for A Good Country. The level of cruelty and debasement: kidnapping millions of people from their continent and enslaving them, trying to breed them like livestock — along with the genocide and forced displacement of the people who were indigenous to this land.

It was not Muslims doing that, it was people who were calling themselves Christian, and often explicitly asserting that their faith made them superior, that it required them to destroy, enslave or assimilate other people.

So, if someone wants to talk to me about Muslims being disproportionately responsible for violence in the world, they’re talking to the wrong sister. Hands down, I’m gonna win that argument.

That’s definitely not the history we’re taught. As a first-generation American whose parents both thrived here, I really embraced the narrative of the U.S. as a melting pot, as a “nation of immigrants” But in A Good Country, you excavate a history of the nation as a settler project — one that is ongoing.

In the story America tells itself, we’ve had our revolution, and now this is a country of “the people.” But who are “the people?” Turns out “the people” are exclusively folks who are not indigenous to this place or who were not brought over by force, and they still have a heck of a lot more political, financial, social power in the U.S. today. The idea that the revolution brought a sort of final reckoning is such a problematic understanding of who we are, but it’s one that we recite to ourselves when we say the Pledge of Allegiance, and when we sing our national anthem.

If we could co-imagine a more hopeful way of thinking about the future, what would it be?

When we look around the planet at its several settler colonial projects, we can ask, within a modern human rights framework, what are our options? There are places like New Zealand, which has decided to take the position: we are now bicultural, which means we will represent and protect the interests and the cultures and the identities of both Maori people and European people.

That is a profoundly different approach to the approach that, for example, the United States and Israel are now taking.

So that’s policy. What about at the community level, at the individual level?

Going back to Jews and Muslims, under the current global constellation of power, we’re both going to be the targets of major fascist campaigns. It’s already happening. So the pragmatic question for us, as fascism rears its head globally, will be: Are we better off separate? Are we better off together?

And then beyond the pragmatic, there’s the call of our respective faiths. We can act in solidarity — with each other and with other target groups, because we’re called to it by the teachings of our own religions.

What if we’re not religious or practicing? What if we’re not even believers?

You know, just the other day I saw a post from my editor at Random House, quoting the Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel: A Jew is asked to take a leap of action rather than a leap of faith.

If I had to recount how I came to faith as a Muslim, the faith didn’t come first. It was practice. The Quran promises all those who believe in God and do good works that they have nothing to fear or grieve. So in the beginning, I thought, well, I don’t know about God, but I can do good works.

And that was my first step: taking a leap of action.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO