The great Burt Bacharach album that nobody’s talking about

Though it stalled on the charts, ‘Reach Out’ is a sumptuous 11-course aural feast

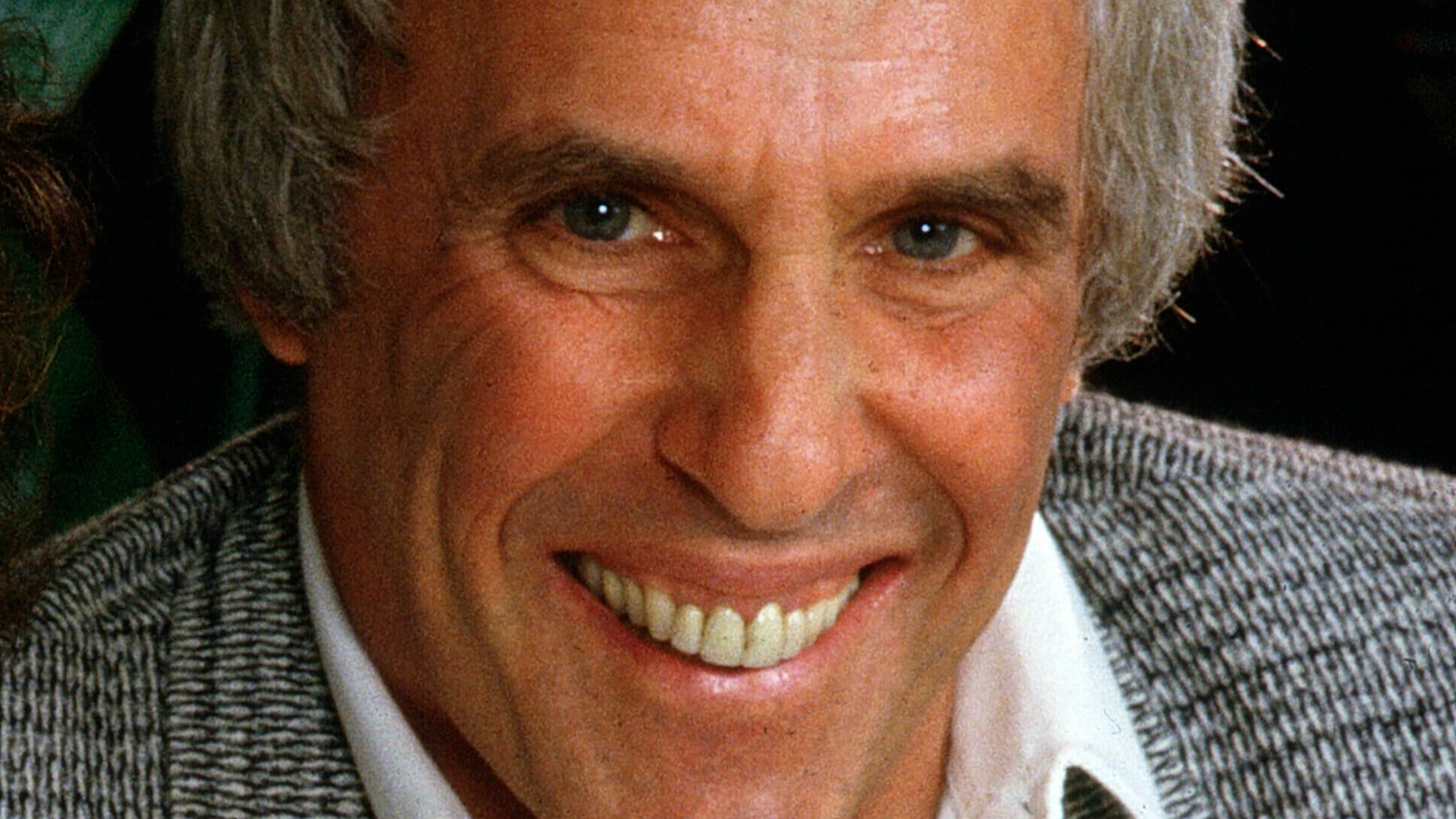

Bacharach at home in Beverly Hills, 1986. Photo by Getty Images

The obituaries for the late, great Burt Bacharach have been pretty much what you’d hope and expect for a true giant of 20th century pop music. Bacharach’s fruitful songwriting collaborations — especially with Hal David, Carole Bayer Sager and Elvis Costello — have been rightfully celebrated, as have his many hits and awards, along with his music’s wide-ranging influence.

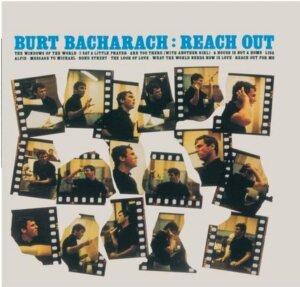

But when you’ve won six Grammys, two Oscars, and had your songs recorded and sent up the charts by the likes of Dionne Warwick, Dusty Springfield, Jerry Butler, Sergio Mendes, Herb Alpert, The Carpenters, The 5th Dimension and Neil Diamond, it’s perhaps inevitable that some of your finest work should get lost amid the glittering prizes. And indeed, Reach Out, Bacharach’s 1967 solo LP, has largely gone unmentioned in his obits — even though it may well be the most perfect album-length distillation of Bacharach’s music ever waxed.

That Reach Out has been overlooked is not particularly surprising, considering that it was basically a commercial flop. Reach Out was Bacharach’s first album for A&M Records, and the label (which was making a conscious effort to avoid the psychedelic fumes wafting out of the “Summer of Love”) released it in September 1967 as part of a multi-artist launch that included similarly adult listener-oriented records by Claudine Longet, Wes Montgomery and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

But despite A&M’s considerable promotional efforts, Bacharach’s already lofty reputation as a songwriter, and the fact that Bacharach’s Casino Royale soundtrack had been a Top 25 hit that summer, Reach Out stalled at No. 149 on the Billboard 200 and dropped straight into the bargain bin — where it has basically resided ever since.

That’s where I found my first copy of Reach Out back in the mid-’90s, for a buck or two at a thrift shop in LA’s Fairfax District. Though long a big fan of Warwick’s Bacharach-David hits, I’d never even heard of the album. But I gleaned from the conductor-ific photos on the front cover (and former Beatles PR flak Derek Taylor’s overblown liner notes on the back) that this was largely an instrumental affair; and since I loved the instrumental arrangements (and the sounds of the instruments themselves) on Warwick’s recordings — like the perky Alpert-esque trumpet on “I Say a Little Prayer,” or the sullenly rolling piano on “Walk On By” — I figured this album might provide more of the same. Which, in retrospect, was a little like saying I figured I might be able to get a snack at my Jewish grandmother’s house.

Musically and sonically, Reach Out is an absolute feast, a sumptuous 11-course aural meal that blends a wide variety of instrumental ingredients to absolute perfection. Nine of the album’s 11 songs are Bacharach-David compositions that had already been hits for other artists, like “The Look of Love,” “Alfie” and “Reach Out for Me,” though this time out they’re arranged to let different instruments carry the bulk of the melodies. (Female voices occasionally swoop in for the choruses, but the verses are strictly vocal-free.) Without the distraction of lead vocals, you’re able to get further inside the music and gain a greater understanding of how Bacharach’s jazzy chord progressions, irregular time signatures and asymmetrical melodies fit together and play off of each other; it’s like pulling off the back of an astronomical clock to view its sophisticated inner workings.

Though there is unfortunately no information in the album’s liner notes or elsewhere as to which musicians actually played on Reach Out, engineers Phil Ramone and Henry Lewy recorded them beautifully. Even on the album’s most dynamic and bombastic numbers, like “I Say a Little Prayer” and “What the World Needs Now Is Love,” the instruments are balanced perfectly with each other, even as their constant movement expands and retracts your perception of the space in which the songs are being played. (A&M may have taken an anti-psychedelic stance, but that clearly didn’t prevent them from releasing mind-blowing music.)

At the end of “Are You There (With Another Girl),” there’s a moment where the rest of the musicians and vocalists fall away, leaving the organist to wrap things up with a liquid little right-hand lick while he holds down a steady bass note with his left. Even when you’re listening to the track in sonically degraded form on something like Spotify or YouTube, you still feel like you’re sitting so close to the organ that you can actually make out the woodgrain of its cabinet; and if you’re listening to it on a good stereo system, that moment can induce full-on goosebumps.

I’ve seen several references online in the wake of Bacharach’s passing to the “schmaltzy” nature of his music. And while he was certainly guilty of going in that direction at times — especially on later hits like “Arthur’s Theme” and “Heartlight” — there’s very little schmaltz to be found on Reach Out. (“Lisa,” a treacly Bacharach-David composition which made its debut here, is the unfortunate exception.)

The album’s overall sound and mood could easily be considered cocktail-friendly, but not in a campy or cheesy way; if anything, the roiling, conflicted and profoundly adult emotions already running through these songs are somehow further magnified here by the lack of lyrics. And on “A House is Not a Home,” Bacharach himself delivers the album’s lone lead vocal in a performance so convincingly bereft, you’ll almost forget that he was actually married to Angie Dickinson at the time he recorded it.

Reach Out’s lack of immediate success didn’t seem to impact Bacharach’s career in any significant way; just two years later, he would write the Oscar-winning original score for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which included the multi-million-selling Bacharach-David song “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head” — and which provided enough of a commercial tailwind to drag both Reach Out and its similar-if-slightly-inferior solo follow-up Make It Easy on Yourself to “gold” status by the end of 1970. But it does seem to have negatively impacted the album’s legacy; for whatever reason, it’s not an album that seems to be taken seriously by critics or musical historians. Even in an age where one forgettable album after another is getting the 180-gram vinyl reissue treatment for Record Store Day, Reach Out hasn’t been reissued in the U.S. since it came out on CD in 1995, just a year or so after I dug up my first thrift shop copy.

Since that fateful day nearly 30 years ago, I have never been without Reach Out in one format or another, and usually in multiple ones; I even recently bought a reel-to-reel tape of it on eBay. Reach Out is truly a “desert island disc” for me, in the same way that, say, Love’s Forever Changes or Queen II are; as with those albums, I feel a rush of intense emotions every time I spin it, while also always finding new things to marvel at in the music, and in the way the songs are constructed and arranged. It remains a wonderfully life-affirming listening experience, yet it’s one that can still be found languishing at thrift shops and antique malls everywhere, nestled ingloriously among all those Vaughn Meader and John Gary albums that no one ever wants to hear again. So reach out for Reach Out — Burt Bacharach may have left us, but his greatest album is still here.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO