‘He Gets Us’ ads are selling Jesus at the Super Bowl. Who is buying?

A well-funded ad campaign aims to give Christianity a makeover

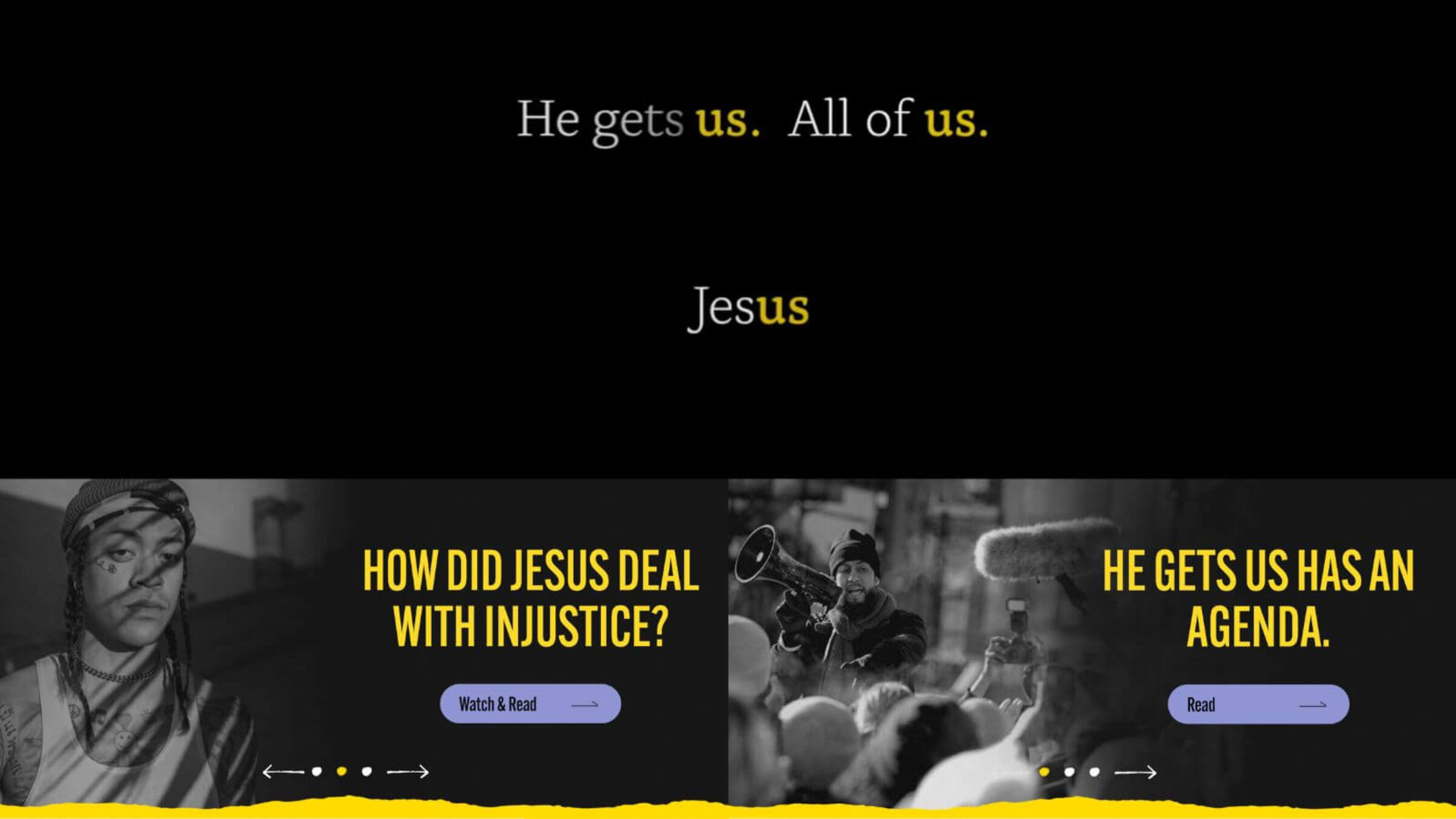

A compilation of images from the He Gets Us site. Courtesy of He Gets Us

Obviously, the Super Bowl is the biggest sporting event of the year. The telecast is also the biggest event of the year for another demographic: advertisers. Placing an ad during the Super Bowl means spending millions of dollars to show a short video that uses a cultural or political reference to try to make us buy chips. It’s fascinating, plus some of them are truly iconic.

But this year, there’s a new product joining the usual collection of beer and deodorant ads: Jesus. No, that’s not a product or corporation. (Well, debatable.) That’s Jesus of Nazareth, the Christian messiah. You’ve probably heard of him.

A nondenominational Christian campaign called “He Gets Us” will run two ads during the Super Bowl, costing about $20 million. The spots, which have already been running during NFL games and other major telecasts, as well as on YouTube, aim to make Jesus relatable to the modern-day American.

Featuring black-and-white photos and emotional music, the ads use narrators to tell the story of someone who sounds just like you or me — only to reveal, at the end, that they were talking about Jesus all along. The story of a family fleeing political upheaval: Mary and Joseph. A doctor who tried to heal everyone: Jesus. Each ad ends with the same words: “He gets us. All of us. Jesus.” (The “us” in Jesus is highlighted in yellow, in case you missed the message.)

He Gets Us is not the first religious ad to run during NFL games: Robert Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots, funded ads in October in response to Kanye West’s antisemitic outbursts. “Antisemitism is hate. Hate against Jews. For being Jewish,” the ad said. “Recently many of you have spoken up. We hear you today. We must hear you tomorrow.”

But “He Gets Us” is not tied to a current crisis, like West’s antisemitic tirades. There’s no specific ask, like standing up to antisemitism. So, what are they trying to do?

Jesus needs a makeover

“He Gets Us has an agenda,” the campaign’s page says. “How did the story of a man who taught and practiced unconditional love become associated with hatred and oppression for so many people?”

“This is a branding campaign. ‘We’re branding Jesus,’ that’s what they’re doing,” said Gary Wexler, a longtime advertising professional — including some major Jewish campaigns — and a professor at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School.

The ads are reminiscent of a 1980s campaign by the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints called the Homefront that promoted family values. Those, too, were carefully apolitical; This was not the anti-abortion, anti-LGBTQ culture-war version of family values we are familiar with today, and there was no overt religious message. Instead, they were emotional PSAs about spending time with your kids. The intention was to rebrand the Mormon church, which was then associated with polygamy and racism. After years of the Homefront ads, the primary association with the church became family.

For the He Gets Us campaign, the goal seems to be giving Christianity a liberal makeover. According to a Jacobin investigation, the He Gets Us campaign is supported by evangelical groups such as The Servant Foundation, an endowment managed by the Oklahoma-based Church of the Servant, and Hobby Lobby founder David Green, both of which are known for giving to conservative causes. (Hobby Lobby won its 2014 Supreme Court case to be religiously exempt from providing healthcare that included Plan B.)

But the He Gets Us ads mine imagery from protests, of refugees along the Mexican border, of masked people in hospitals during the pandemic. There’s a page on how Jesus supported women’s equality. The campaign uses hashtags like #refugee and #activist that are associated with progressive causes. Yet it remains carefully vague, unmoored from any actual current events and devoid of a political stance.

After showing scenes of overwhelmed hospitals and tired healthcare workers invoking the pandemic, the ad concludes: “Jesus felt heartbreak too. He gets us. All of us.” There’s no overt mention of COVID-19 or confirmation of its reality, much less an exhortation to get vaccinated.

Another shows scenes of weeping teens at vigils — the kind that look familiar from school shootings. But there’s no message about gun control or violence; the text merely reads, “Jesus wept. He gets us.”

Some evangelicals are skeptical of the ads, complaining that the ads are too wishy-washy and don’t touch on the most essential part of Jesus: his divinity. Others are frustrated by the liberal-feeling politics in the ads.

But they’re not the target audience. Instead, He Gets Us is trying to respond to the steep drop in the numbers of Christian Americans; in 1972, 90% of Americans were Christian, compared to just 64% in 2020. A recent Pew survey projects that, if numbers fall at the current rate, less than half of Americans might be Christian before another 50 years have passed.

“This is very strategic,” Wexler said, acknowledging that many in the evangelical world likely don’t back many of the liberal issues hinted at by the ads. “They know who their audience is, they know how to cast this net, how to intimate things without saying ‘This is what we’re doing.’”

OK, Jesus gets us. So what?

Jason Vanderground, a spokesperson for He Gets Us, said the campaign’s goal is to “unify the American people around the confounding love and forgiveness of Jesus,” seemingly unaware of the fact that Jesus is not so unifying to all Americans. It’s hard not to see the campaign as a conversion drive.

In an op-ed for Religion News Service, Rabbi Joshua Hammerman wrote that the ads make him nervous as a Jew. “Notice that Vanderground did not say ‘unify American Christians.’ He wants to unify all Americans under the banner of the cross. That includes me,” Hammerman wrote.

But the He Gets Us site, where the ad directs viewers, makes no conversion attempts. In fact, one page specifies that it’s not even asking people to attend church or have a religious experience. It simply gives some reading options about Jesus, asking people to “consider the story of a man who created a radical love movement” and be inspired “to love others better.”

The closest thing to an ask from viewers — a way to get them engaged and channel them into some form of action — is an option to text a number for “prayer” or “positivity.” Receiving those texts are volunteers, gathered from 20,000 churches who have signed on to help the campaign with manpower, though not money, Vanderground told The Washington Post. (When I tried to text the number, it took a day to get a response, which was devoid of any directly Christian elements. “Praying for your needs today. May the Lord provide for you and walk with you through whatever you’re facing. God bless you,” it said.)

Wexler thinks He Gets Us is more focused on people already in, or connected to, evangelicalism.

“They’re aiming these at the concerns of a new generation, so they’re trying to pull these people in. I wouldn’t even jump to the conversion thing at this point,” he said. “They’re trying to build up their own roles and the people who are involved.”

Still, this is just the first stage of the campaign; Vanderground said He Gets Us is planning to invest a billion dollars on promoting Jesus over the next three years, putting its budget on par with many major brands. And Wexler is sure there will be clearer actions later on.

“In order for these people to be counted, and for these people to become active Christians, they’ve got to be funneled into churches or organizations of some type. Otherwise they’re not part of the community,” Wexler said. “They’re not going to pour all this money just in this way. I’m sure they’ve got a plan.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO