He captured a side of Bob Dylan that hadn’t been seen before

Daniel Kramer’s 1960s photographs showcased the artist at his most playful and appproachable

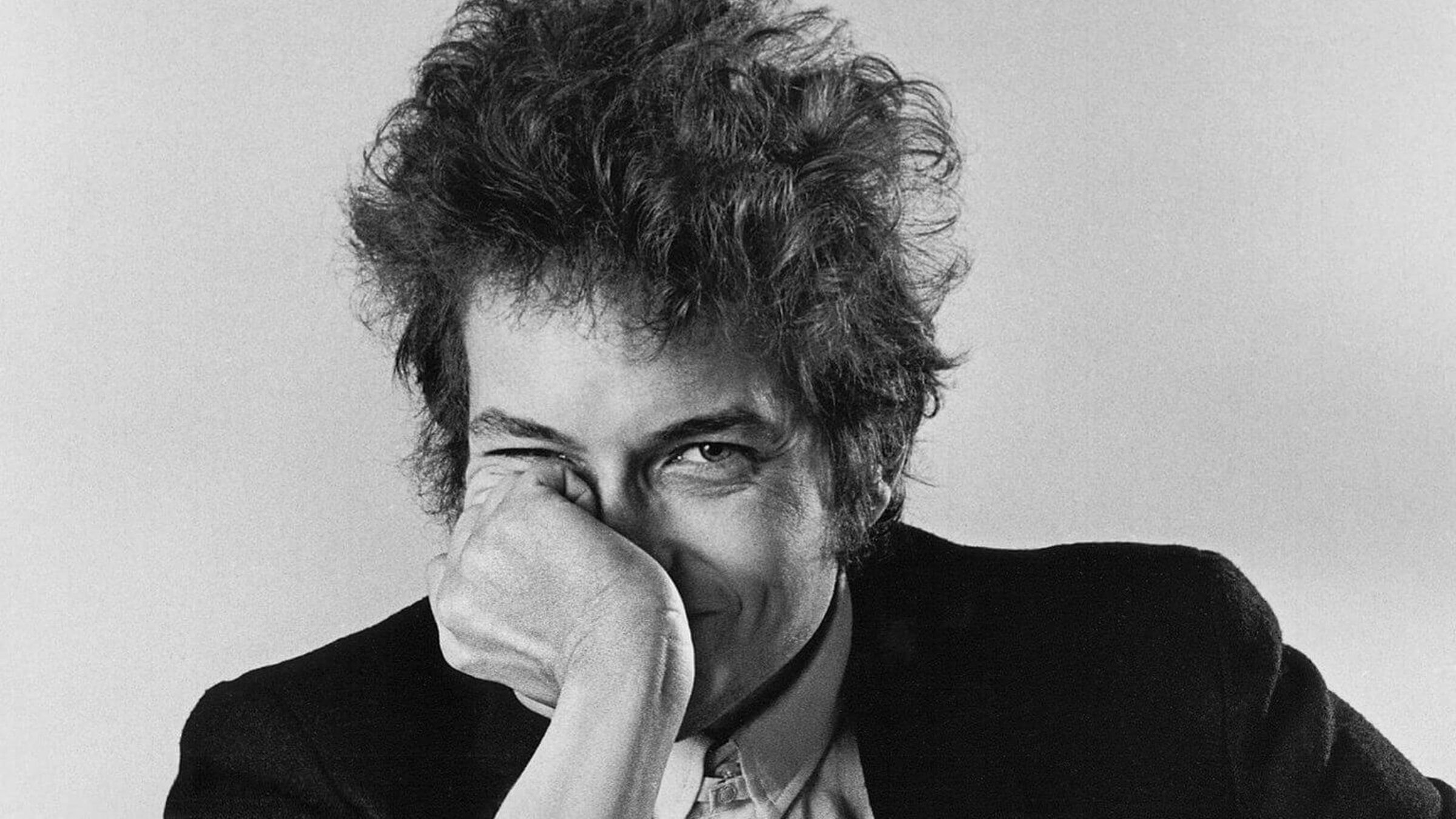

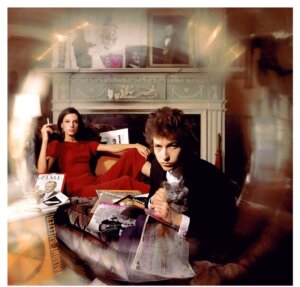

Photographer Daniel Kramer said he and Dylan developed a rapport because they shared similar backgrounds and interests. They were “like cousins,” he said. Photo by Daniel Kramer

For six decades, Bob Dylan has been an enigmatic musical and cultural force. At 81, he continues to make new albums and tour. He’s never too far out of sight or out of mind, whatever the platform.

Like many, I’ve jumped on and off the Dylan train over the decades. . But there’s little debate about the importance of his early years musically, and as it turns out, photographically.

Don’t Think Twice: The Daniel Kramer Photographs of Bob Dylan, 1964-65, an exhibit at Boston’s Boch Center Wang Theatre, was originally supposed to hit Boston in 2020, but the pandemic lockdown killed that and then another planned opening was nixed by a second Covid-19 wave. Third time’s the charm.

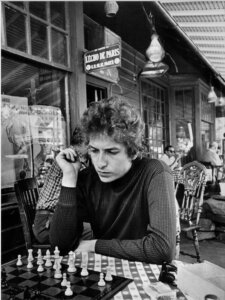

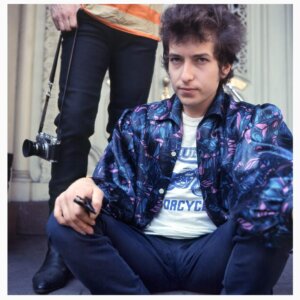

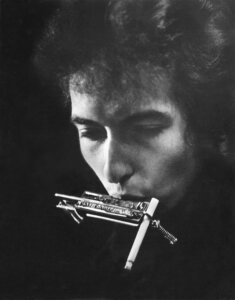

Kramer’s 51 photos, most in starkly beautiful black-and-white, give a window into a special period for Dylan and pop music in general. Dylan was pushing the limits of what could be expressed in song in length and lyrics, with his hurtling verses, and in sound. It was clear pop music could turn a corner toward, at least potentially, a more worldly phase.

Kramer’s photos can jettison you back to that time — even if you weren’t alive or sentient then. Maybe it’s 20/20 hindsight, but the confident, playful air about Dylan then suggests a feeling that he knew he was on the cusp of something great. He was not yet the superstar he’d become. Nor was he the unspeaking, even-more-gruff-voiced, non-guitar playing Dylan audiences have seen in the last few years.

Kramer had well-established photographic credentials before Dylan came into his orbit. But before this ultimately symbiotic process even began, Kramer says, “People said he won’t come to the studio and pose for you, and I said ‘Like hell he’s not.”

Kramer, who talked with me via email, said Dylan hemmed and hawed when he got him on the phone. “I said ‘You give me one shot and if you don’t like it, we won’t do it anymore,’” Kramer says. “He came.”

And he liked it. The first picture Kramer took, within 20 minutes of the meeting, was of a relaxed Dylan reading a newspaper, one of the 51 in the current exhibit. Many of the photos were, like that one, impromptu, says Kramer.

The working relationship expanded into a friendship, where Kramer had unprecedented access. Dylan was clearly comfortable with Kramer’s presence; Dylan loved the camera and the camera loved him. Aside from the striking concert shots, Dylan lifted the veil and Kramer was there to capture sides of Dylan he hadn’t previously revealed — pictures of Dylan shooting pool, playing chess, mugging with a wide-eyed Joan Baez as he mockingly irons her hair, cigarette dangling from his lips, or looking faux-fierce posing with Johnny Cash.

From folkie to rocker

“Dylan hadn’t done that for any other photographer,” said Bob Santelli, the exhibit’s curator, who was at the opening party in Boston. “It couldn’t have come at a better time in the history of American music or Bob Dylan’s history. This is about the transition of Bob Dylan from folksinger, the heir to Woody Guthrie, to a rock artist who brought with him not just a brand-new sound but poetry and significant meaning to rock ‘n’ roll lyrics.”

David Bieber, a collector who runs the David Bieber Archives in Norwood, Massachusetts, told me the photos convey “that sense of intimacy and informality, the accessibility, where he was transforming himself from a folk performer to a songwriter other people were recording and finding acceptance of his own voice.”

“The all-seeing eye of Kramer’s camera captured a moment in time you wouldn’t see again,” Bieber said. “Now, Dylan is on this never-ending tour where he goes from tour bus to stage, back to tour bus. He’s almost a ghost of his former self, the myth preceding the man.”

Kramer, who is now 91, was with Dylan, off and on, for a year. “There were no set times or poses and it wasn’t all in one timespan, but several times over that year,” Kramer said. “There was not an agreed-upon time frame or limit. I recall getting a call and him asking me what I was doing. I said ‘I am working in the studio.’ He said ‘Well, why don’t you come out and take some pictures?’”

Needless to say, Kramer was on his way.

“There was one time we spent three days in Buffalo,” Kramer recalled, “and then we were at the studio for two weeks. Then maybe I didn’t shoot him for two weeks, but then we went again.”

The connection they had for that period of time ran deep. “Everything about us was the same,” Kramer says. “Jewish, parents, what your father did for a living, everything. We were like cousins. Working with Dylan was like working with me. That’s why we got along; we were crazy.”

Watching Elvis movies

How crazy?

“As long as I was willing to go to the apartment at 5 or 6 p.m. to watch Elvis Presley movies, he was fine,” Kramer said. “He wanted to be Elvis Presley when he grew up.” Which is to say, Dylan would work with Kramer all day, if he would promise to join him for an Elvis flick at the end.

This is not to say everything went smoothly. “It’s who he is as a musician,” said Kramer. “It was hard at times working with him, but that is why my pictures are so good. I did not take him away from his work, I kept him in it.”

While the bulk of the photos at the exhibit are black-and-white, Kramer did the color album covers for Highway 61 Revisited and Bringing It All Back Home. Bieber told me he prefers the black-and-white photos, but sees the colorful album covers as possibly allegorical: “You could say at that time Dylan’s music went from black-and-white to color,” Bieber said. “In 1963, [Dylan was about] Peter, Paul & Mary and protest songs and in 1965 he was hanging out at the Factory in Andy Warhol’s world.”

In the summer of 1965, Dylan was in one of those periods of reinvention for which he’d become well-known. On Aug. 28, Dylan played Forest Hills Stadium in New York, and Kramer took some stunning photos. “He went electric and going electric changed everything,” Kramer said. (This was about a month after Dylan’s infamous “coming out” at the Newport Folk Festival.)

There was no fallout, no acrimony; the project had run its course and each was ready to move on. Kramer says he’s remained a fan of Dylan music, if not the entirety, “for a lot of it.”

You know what the mercurial Dylan has done since, probably in great detail. As for Kramer, he continued to build an impressive and diverse resume, which included everything, really, including landscapes around the world, U.S. presidents, in-house corporate reports for Morgan Stanley, boxer Joe Frazier, novelist Norman Mailer and singers Baez and Janis Joplin.

Don’t Think Twice: The Daniel Kramer Photographs of Bob Dylan, 1964-65 runs through March 29 at Boston’s Boch Center Wang Theater as part of its Folk Americana Hall of Fame Roots series.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO