In Kafka’s diaries, harsh criticism and sympathetic fascination for his fellow Jews

Newly translated diaries shed light on the author’s views on Jewish culture and customs

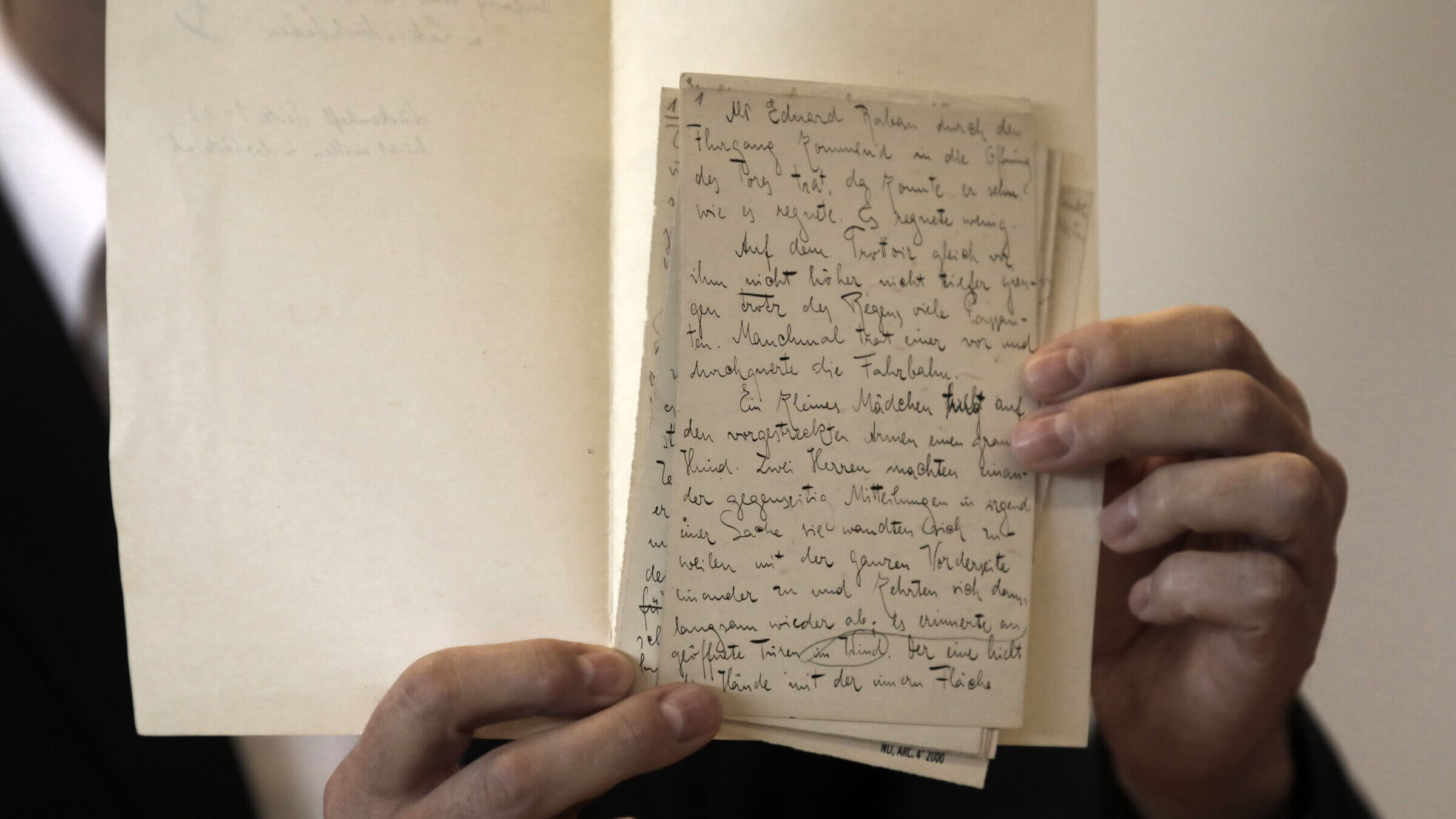

Franz Kafka’s manuscripts are displayed during a 2019 press conference at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. Photo by Getty Images

The Diaries of Franz Kafka

Translated by Ross Benjamin

Schocken, 745 pages, $45

A long overdue new translation of an authoritative German language edition of Franz Kafka’s diaries that appeared in 1990 offers welcome insight into the Bohemian novelist’s evolving concepts of Judaism.

The translator, Ross Benjamin, is alert to Jewish nuances in Kafka’s discourse, although in a preface, may overstate matters at times. One example pertains to how, when in close contact with a friend, the Yiddish actor Jizchak Löwy from Lemberg, Kafka feared “at least the possibility of [contracting head] lice.” The translator proclaims: “Here Kafka confronts his own Western European Jewish anxiety about the hygiene of his Eastern European Jewish companion.” Yet in the matter of head lice, for someone as health-obsessed as Kafka, Judaism would have been irrelevant.

More impressive here is the attentive care for the original German text, provided for the first time in English to replace his friend Max Brod’s sanitized version, intended to give the best possible image of his dear friend Kafka.

The English Jewish author Will Self, in a review, claimed that the present new edition “gives us a sketchier Kafka, both morally and artistically.” Yet the reverse may be true, as the fuller text provides a more accurate portrait of Kafka, closer to reality and therefore more artistically valid. The result is in no way dishonorable to Kafka.

On the contrary, his obsessive interest in things Jewish reflects admirably on him. In 1911-1912, Kafka attended almost two dozen performances by Löwy’s traveling Yiddish theater troupe during their guest season in Prague.

Kafka reveled in the company of exuberant theatricals. He was drawn to them with the fascination of an anthropologist or entomologist who makes value judgments as part of an awareness of the futility of human endeavors.

For Kafka, these performing Jews were exultant conveyers of song and dance. Onstage, two actors represented “Jews in an especially pure form, because they live only in the religion but live in it without effort, understanding or misery. They seem to make a fool of everyone, laugh immediately after the murder of a noble Jew, sell themselves to an apostate, dance with their hands on their sidelocks in delight when the unmasked murderer poisons himself.”

Details such as the pronunciation of the term yiddishe kinderlach (Jewish children) or an actress who “because she’s a Jew draws us listeners to her because we’re Jews” sent a “tremor over [Kafka’s] cheeks.”

The music of the Yiddish language is accompanied by a kind of choreography, in theaters and in real life. In October 1911, Kafka describes an actress, Mania Tschissik, singing “Hatikvah” as she “slightly rocked her large hips and moved her arms, bent parallel to her hips, up and down with cupped hands as if she were playing with a slowly flying ball.” In February 1913, Kafka similarly wrote to his fiancée Felice Bauer about a visit to an Eastern European Jewish timber merchant whose choreography of hand movements accompanied his “Talmudic melody” of speech.

Kafka was an outsider in terms of everything, including Jewish ritual observance. In December 1911, he recounted the ultra-Orthodox custom of metzitzah b’peh (direct oral suctioning), when at a bris, the mohel sucks blood away from the baby’s circumcision wound. Under the pseudo-ethnographic heading “Circumcision in Russia,” Kafka notes some details worthy of Nikolai Gogol: “The circumciser, who officiates without payment, is usually a drunkard, since busy as he is he cannot participate in the various feasts and therefore only tosses down some schnapps. All these circumcisers thus have red noses and bad breath.”

By nature, Kafka was a warts-and-all portraitist who saw flaws in all actions by Jews, perhaps because Jews as humans are necessarily flawed. In an October 1911 account of a lecture hall presentation, Kafka implied that the poet Chaim Nachman Bialik translated his poem “In the City of Slaughter,” about the Kishinev pogrom of 1903, as a career move, to advance himself as well as the political future of the Jews. According to Kafka, Bialik “lower[ed] himself” from Hebrew to the vernacular “to popularize his poem exploiting the Kishinev pogrom for the Jewish future.”

Bialik’s exhortatory poem promoted activism, inspiring young Jewish people to abandon the passivity of pacifism and combat Czarist tyranny. Kafka was innately not an activist about anything, apart from his own writings. Ironically, by 1911, Bialik was experiencing his own doubts about his public role as prophetic bard, and was producing few poems.

Kafka’s claim that he mainly sympathized with Yiddish actors as fellow professional failures (“sympathy over the sad fate of many noble endeavors and above all our own”) may understate the real affinities he felt for them. He could be a harsh critic, and in January 1911 criticized the novel Spouses by the German Jewish writer and attorney Martin Beradt as a “lot of bad Jewishness” with “minor characters mostly dismal.”

Kafka aesthetically judged a fellow lawyer whose life was, at least externally, more eventful than his own, but without the posthumous glamor that would accrue to Kafka due to the latter’s enduring literary achievement. Beradt’s books were burned by the Nazis in 1933, and his papers, now housed at New York’s Center for Jewish History, detail how military service on the Western front during World War I followed by work in copyright protection for authors meant nothing after Nazi laws came into effect. Beradt and his wife fled as refugees in 1939, arriving in New York. There Beradt’s wife worked as a hairdresser while, Beradt, whose literary career was permanently destroyed, lost his eyesight.

Although Kafka was long dead when these events played out, his note from December 1911 about lack of “significant talents” among certain Jewish writers seems pertinent, since he added the observation that the “[Jewish] people remain, of course, and I cling to them.” This human connection is also expressed in informal jottings, such as one in January 1912, when a dubious interpretation of Jewish lore appears: “Talmud: He who interrupts his studies to say, how pretty this tree is, deserves death.”

This version of a passage from Chapter 3, Mishna 9, of Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) quotes Rabbi Shimon to the effect that “one who walks on the road while reviewing (his Torah study) and then stops his study and says: ‘how beautiful is this tree’ or ‘how beautiful is this plowed field,’ scripture regards him as if he is liable for his soul.” To which the medieval French rabbi Rashi in his Talmud commentary noted that the phrase “liable for his soul” meant “puts himself in danger” insofar as someone idly talking, instead of being fully absorbed in Torah, is vulnerable to attack from Satan.

Despite these vagaries of meaning, Kafka’s devotion to Jewish culture remained constant. By March 1922, he was even more secure as an arbiter of Yiddishkeit. Describing the Maccabi Jewish Gymnastics and Sports Association children’s Purim celebration, in which his 9-year-old niece Marianne Pollak participated, Kafka, who watched with admiration, delight, and tears, bemoaned that “little Jewish feeling” was involved.

This new complete version of Kafka’s diaries, finally available in English, makes the writer’s legacy all the more deeply imbued with Jewish feeling.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO