Bintel BriefMy daughter said I’m ‘code-switching.’ Is that such a bad thing?

Bintel helps a dad figure out if he hides Yiddish vocabulary due to internalized antisemitism

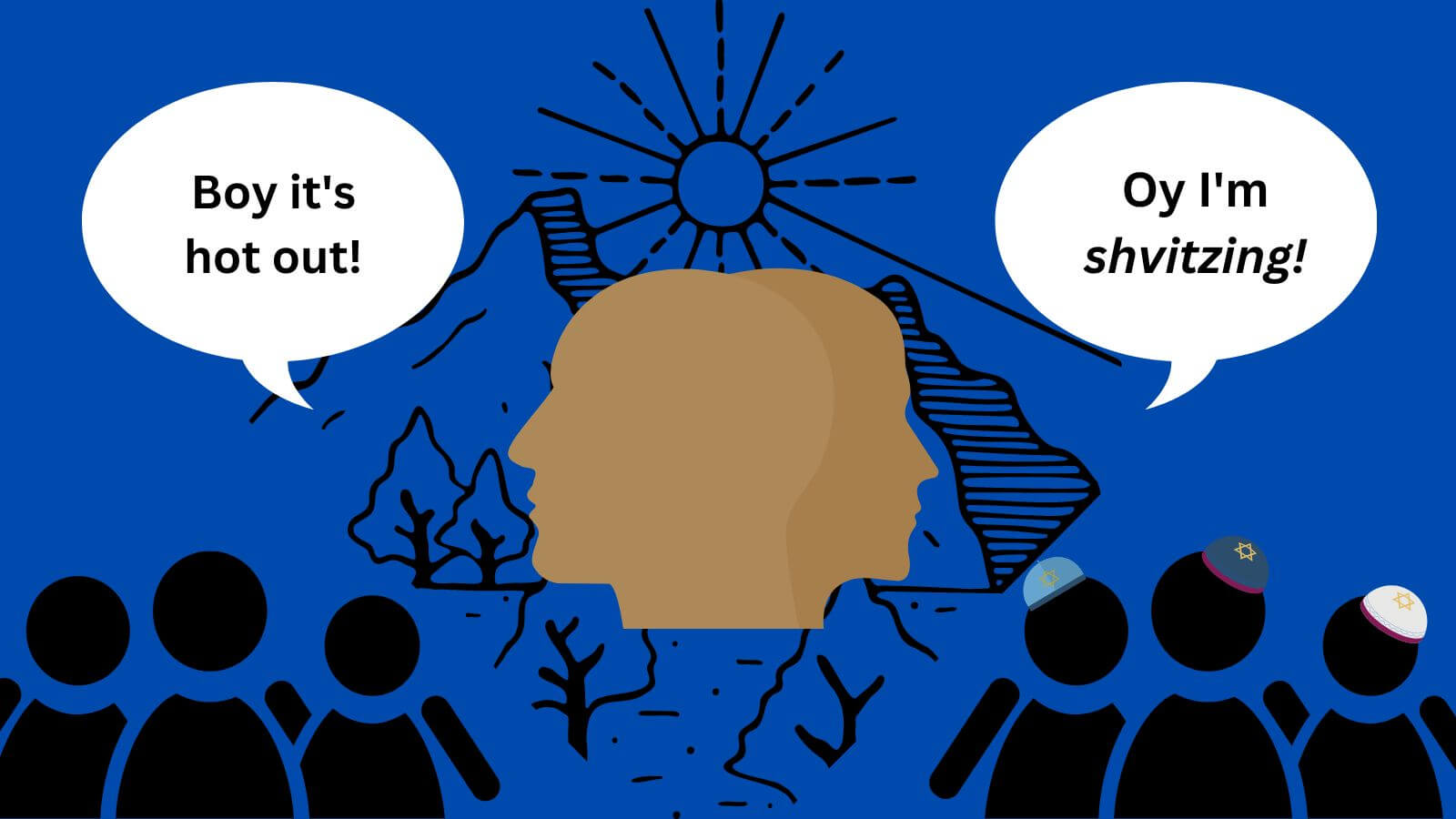

To sweat or to shvitz, that is the question. Illustration by Mira Fox

The Forward has been solving reader dilemmas since 1906 in A Bintel Brief, Yiddish for a bundle of letters. Send us your quandaries about Jewish life, love, family, friends or work via email, Twitter or this form.

Dear Bintel,

Recently, when I was out with my daughter, she told me something I had never heard before — that I code-switch.

The example she used: When I’m hiking with the men’s group from my synagogue, I shvitz. When I’m with my daughter and her non-Jewish friends and parents, I sweat.

Is this code-switching a bad thing? My daughter says it’s from unconscious antisemitism. But I think it’s just trying to read the room.

Do Jews code-switch when outside the Jewish community? I’d like to think, as someone who grew up with Mel Brooks movies, that Yiddishisms and Jewish phrases are commonplace. Though now that she has called me out, I guess I do refrain from using “Jewish words” in public around non-Jewish friends.

Sincerely,

A Farmisht Father

Dear Farmisht,

The official definition of code-switching is switching languages mid-conversation so, yes, every time you inject Yiddishisms into English conversation, you’re doing it.

But your daughter is talking about a broader, more complicated and often pernicious phenomenon that has, over the past decade, become core to discussions on race and culture. She’s noticing that you seem to switch languages between conversations, specifically in order to fit in with the group — and suspects it might be rooted in some kind of shame about your Jewishness.

That broader phenomenon of code-switching involves not just changing your words or dialect, but altering the entire way you express yourself — what vocabulary you use, your mannerisms, your tone — in order to try to conform to the majority culture. And since that majority culture is usually white and Christian, that modulation of language and behavior usually means trying to sound less like a member of a minority group.

Your daughter is worried that you’re suppressing your Jewishness in capitulation to the white, Christian hegemony. And, specifically, that you’re doing so because you, too, believe that Jewishness is somehow uncouth or embarrassing — that underneath your love of Mel Brooks and your Jewish men’s group, you also harbor a little bit of self-hatred.

But why, exactly, we code-switch is much more complicated than it seems, and it’s rarely because we believe that sounding mainstream, or sounding less like a minority, is objectively better.

I reached out to Leah Donnella, a college acquaintance who is now an editor at NPR’s Code Switch podcast, to get a bit more insight.

She pointed out that we all code-switch pretty much constantly — and usually in innocuous ways.

“Think of the way that many people raise the pitch of their voices and start cooing when they’re ‘talking’ to a baby, or that lilting, high energy way people talk to dogs,” Donnella said in an email. “I would guess the daughter in this situation sounds super different in all of these settings without consciously thinking, ‘I’m using my “friend” vocabulary now. I’ll switch to my “mom” vocabulary at dinnertime.’”

Of course, sometimes we code-switch in much more loaded ways, by concealing an accent or changing our vocabulary. Usually, it’s largely unconscious, Donnella said, based on our assumptions about the people we’re with and how we think they might react.

Which means you are just reading the room, Farmisht, like you said. And you seem to think the room is unfriendly to your Jewishness.

Much like your daughter’s accusation of internalized antisemitism, some people say that Black people code-switch in white spaces because of “internalized anti-Blackness.” But Donnella, who is Black and Jewish, sees this instead as a defense against experiencing worse discrimination.

“When Black people in white spaces fail to conform to traditionally white patterns of speech, they are constantly told that they can’t be understood, that they speak ‘too fast’ or ‘with too much slang’ or some other barely coded way of saying they sound too Black,” she said.

Similarly, when you’re the only Jew in a group, perhaps you avoid broadcasting your identity for fear of a snide comment or an unwanted political discussion. Or maybe you experienced bullying as a child for your Jewishness, so now you’re careful about revealing your whole self.

Or maybe not. It might just be the simple worry that non-Jews won’t understand you. I know I have to remind myself to omit certain phrases when I’m around my non-Jewish friends because, while words like schlep and chutzpah are basically English at this point, dafka and frum aren’t. Frum, in particular, requires an understanding of Jewish cultural context.

So I guess that all goes to say that code-switching isn’t a “bad thing,” as you asked. Sure, it can be tied to “bad things,” like racism and bias, but it isn’t always. At worst, you’re protecting yourself from discrimination — which is pretty reasonable — and at best, you’re just making sure your friends get your jokes.

Besides, your daughter’s concern might be about something else altogether. As Donnella concluded her email to me: “My (very unscientific) belief is that people are hardwired to find whatever their parents do to be humiliating/basic/painfully uncool.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO