Bernie Madoff is the original scammer. Why did it take so long to get a Netflix show about him?

Amidst a glut of true crime shows about scammers and cult leaders, Madoff’s Ponzi scheme seems like an obvious topic

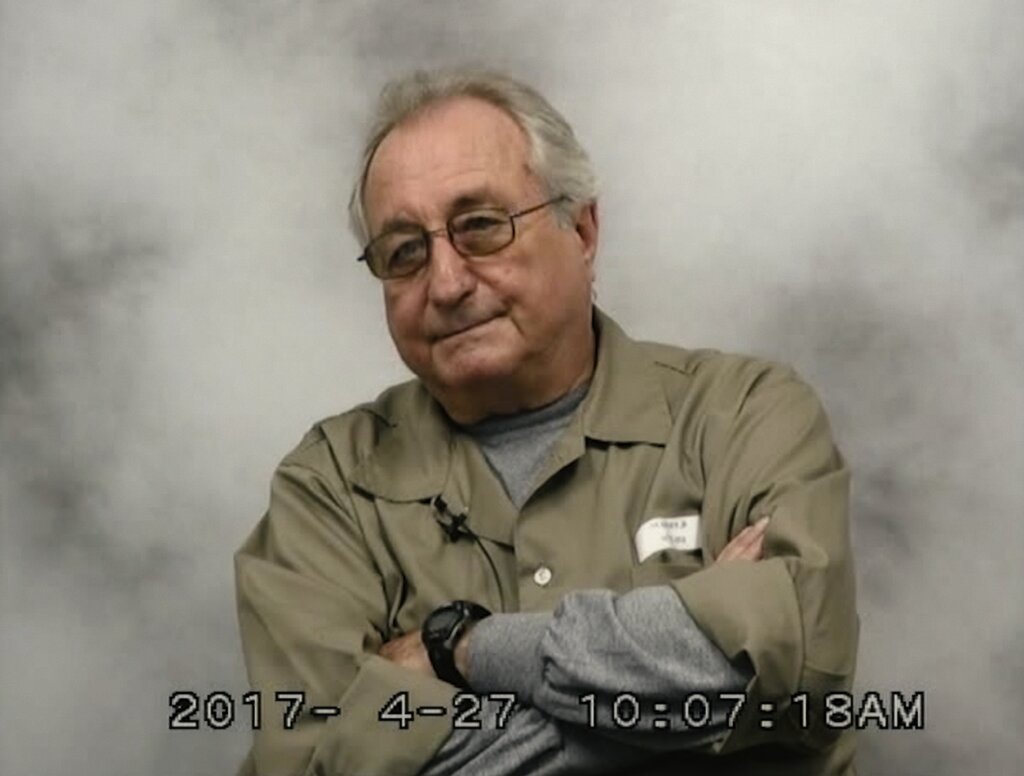

Bernie Madoff and fellow employees. Courtesy of Netflix

We’ve been in the era of scammer documentaries for years now. There was The Vow, which detailed NXIVM, and Wild Wild Country about the Rajneeshees. Tiger King took early-pandemic Netflix watching by storm. LuLaRich dealt with the phenomenon of multi-level marketing and Bad Vegan took on a famous restauranteur’s embezzlement. Fake socialite Anna Delvey got an entire scripted series with Inventing Anna.

Yet the most famous scammer of them all somehow flew under the radar — at least until now. Why has it taken so long to get a Bernie Madoff Netflix show?

Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street is a four-part series, directed by Joe Berlinger, who is most recently known for slickly-edited true crime documentaries such as Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes. He gives Madoff a similar, serial-killer treatment, sketching out Madoff’s family and life, interviewing his former assistant Eleanor Squillari and including excerpts of the financier’s jumpsuit-clad testimony after he was nabbed.

Fascination with Madoff is nearly endless; in the aftermath of his scheme, his wife and sons generated years of tabloid coverage, and there’s been numerous books, movies and even an experimental film about him. The Netflix show is far from the first exposé on Madoff, but it’s the first made for a streaming giant, served up for millions of viewers to binge. (Which they are; the miniseries has staked out a spot in Netflix’s top ten.)

Madoff is, in many ways, the original scammer. Not literally, of course — there have been people cheating each other for personal gain probably about as long as there have been people — but his Ponzi scheme was so successful, so huge and so tied to global institutions that its fall, in 2008, shook the entire global financial system.

But the thing about financial crimes, especially ones that turn on Wall Street-style machinations, is that they’re just not that sexy. Falsifying stock sales, no matter the enormity of the impact, has nothing on Keith Raniere branding the members of his NXIVM sex cult.

Perhaps that is why streaming giants largely stayed away from the story. Much of the Netflix show covers — in admirable depth and with impressive research — the mechanics behind Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, laying it out as clearly as possible. There are the “feeder” funds that kept the scheme afloat and their connections to major investment firms. The way Madoff’s legitimate brokerage firm and the secretive “wealth management” arm on the hidden 17th floor propped each other up. Experts explain the mathematical calculations that first showed Madoff’s returns were impossible, and tell us exactly what a hedge fund is. There’s a strange focus on the dot-matrix printers Madoff still used, and copious references to the SEC.

“Anybody in finance would know, for example, that the number of option contracts that he would’ve required to execute his split-strike conversion strategy exceeded the entire universe of options in existence,” the director told Vanity Fair of Madoff’s fake investment scheme.

That could very well be true, but to me — and probably to most people binging the show — that sentence might as well be in a foreign language.

There’s no flamboyant, mulleted man breeding tigers or settlement of red-clad cult members plotting to poison a small Oregon town. Madoff was, to the end, calm and seemingly reasonable, well-dressed without being flashy. This was core to his scam, of course — it’s why retired Jews in Florida and the elite of New York all trusted him as one of their own, forking over their entire life savings to the Ponzi scheme — but it’s hard to sell as good TV.

So, to add drama, Berlinger sprinkles in details about Madoff’s life, which are as fascinating as they are confusing. Squillari, the assistant, emphasizes Madoff’s love for his family; in a shot of the financier before his sentencing, he chokes up talking about his wife. In other interviews, however, experts hypothesize that Madoff was a sociopath who valued his family only for their adoration, and former employees testify that Madoff would rage if the office computers weren’t perfectly straight. Berlinger even reveals that since Madoff’s 2021 death in prison, his ashes have remained in a lawyer’s possession, his family unwilling to claim them. A cohesive picture of the man never quite emerges.

And that’s because Madoff himself is, in a way, tangential to the real story Berlinger is telling, which is one of regulatory failure. Over and over, the series makes clear, whistleblowers attempted to report Madoff, and over and over the SEC failed to look closely enough. At one point, Madoff even gave SEC investigators banking information that was completely false, but they simply never checked, allowing the scam to continue unchecked for several more years.

Of course, we remain curious about the more human details about why this worked. What about Madoff allowed him to cultivate such loyalty? How did he get away with it? The desperate desire, part schadenfreude and part self-protection, to understand the minds and manipulation of criminals is what makes scammer stories so addicting.

And it keeps us engaged as Berlinger leverages that fascination into a far more important, if drier, message, one less about untangling the minds of an individual criminal and more about untangling government corruption. The director told Vanity Fair he hopes to warn viewers of the dangers of financial fraud, especially in light of the recent collapse of FTX; Berlinger compared Sam Bankman-Fried’s scam to Madoff’s.

So if Berlinger is able to make a story of governmental regulatory failure sexy — or at least gossipy enough to keep viewers’ attention — that seems like a public service. People might not read The Financial Times, but they sure watch Netflix.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO