Will we ever know the impact the Nazi regime had on this groundbreaking female artist?

Surrealist star Meret Oppenheim fell into depression and creative rut for 18 years, during and after the war

The fur-lined teacup shot Oppenheim to fame; people found it sexual, absurdist and confounding. It became the first piece by a woman artist in MoMA’s collections, where it is regularly on display. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Meret Oppenheim was haunted her entire life by a teacup. Object, also sometimes called “Breakfast in Fur,” instantly became one of the quintessential pieces of surrealist art when Oppenheim created it by covering a teacup, saucer and spoon with gazelle fur in 1936, when she was 23.

But it was a high she was not to return to for decades. When Object debuted in a landmark Paris exhibition, Exposition surréaliste d’objets, put on by surrealist tastemaker and theorist André Breton, Oppenheim became the darling of the vibrant Paris art scene. New York City’s Museum of Modern Art bought it, its first acquisition from a woman. But the next year, she was forced to leave it; pushed out by the Nazi regime, she hunkered down in Switzerland, where her family had also fled. This period, beginning in 1937, marked an 18-year depression and creative rut, from which Oppenheim emerged a very different artist.

Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, a retrospective currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art, traces Oppenheim’s career, from her high school pencil sketches to her late-life sculptures and oil paintings. Nearly impossible to categorize, the artist’s work includes jarringly strange objects made of found materials, like Object, but also dreamy paintings, Cubist-inflected sculptures, mediums including brass and wood and oil and collage, and themes like Jungian psychology, androgyny and Greek mythology.

The only defining element of Oppenheim’s work is her stubborn defiance of category; near the end of her life — she died in 1985 — she meticulously curated her own retrospective for a 1984 exhibit in Bern, drawing pages of miniature sketches of her work and organizing them into an exhibition to ensure that she defined her own legacy. (The MoMA retrospective, which also showed at Kunstmuseum Bern and Menil Collection in Houston, partially hewed to these instructions.)

So perhaps it is not surprising that she also defied the category of Jew. The MoMA exhibit shies away from describing Oppenheim or her — very secular — family as Jewish, instead saying her move to neutral Switzerland was motivated by persecution for the family’s “Jewish last name.” (Her mother was a non-Jewish Swiss citizen, which enabled their move to the Alps.)

Yet Jewishness clearly had a huge impact on Oppenheim’s life and artistic trajectory. Most exhibit rooms are brimming with the results of the artist’s lifelong chaotic productivity, but one is sparsely hung, covering her lengthy depressive period, starting when she returned to Basel in 1937, and including the entirety of World War II, which was likely caused, at least in part, by her forced separation from the famous Parisian art and café scene of the era.

Until she departed, the Parisian milieu clearly shaped Oppenheim’s work. The famous Object was the result of a cafe chat with Pablo Picasso and photographer Dora Maar, who remarked on a fur bracelet of Oppenheim’s. At 19, she modeled for Man Ray. Marcel Duchamp mentored her. She was briefly, and torridly, Max Ernst’s lover.

But though she remained in contact with many of the towering figures of Parisian surrealism, Oppenheim’s forced return to Switzerland removed her from a creative community that had, until then, been a source of creative inspiration and encouragement. It seems likely that her return to Switzerland was, at least in large part, responsible for her lengthy creative block.

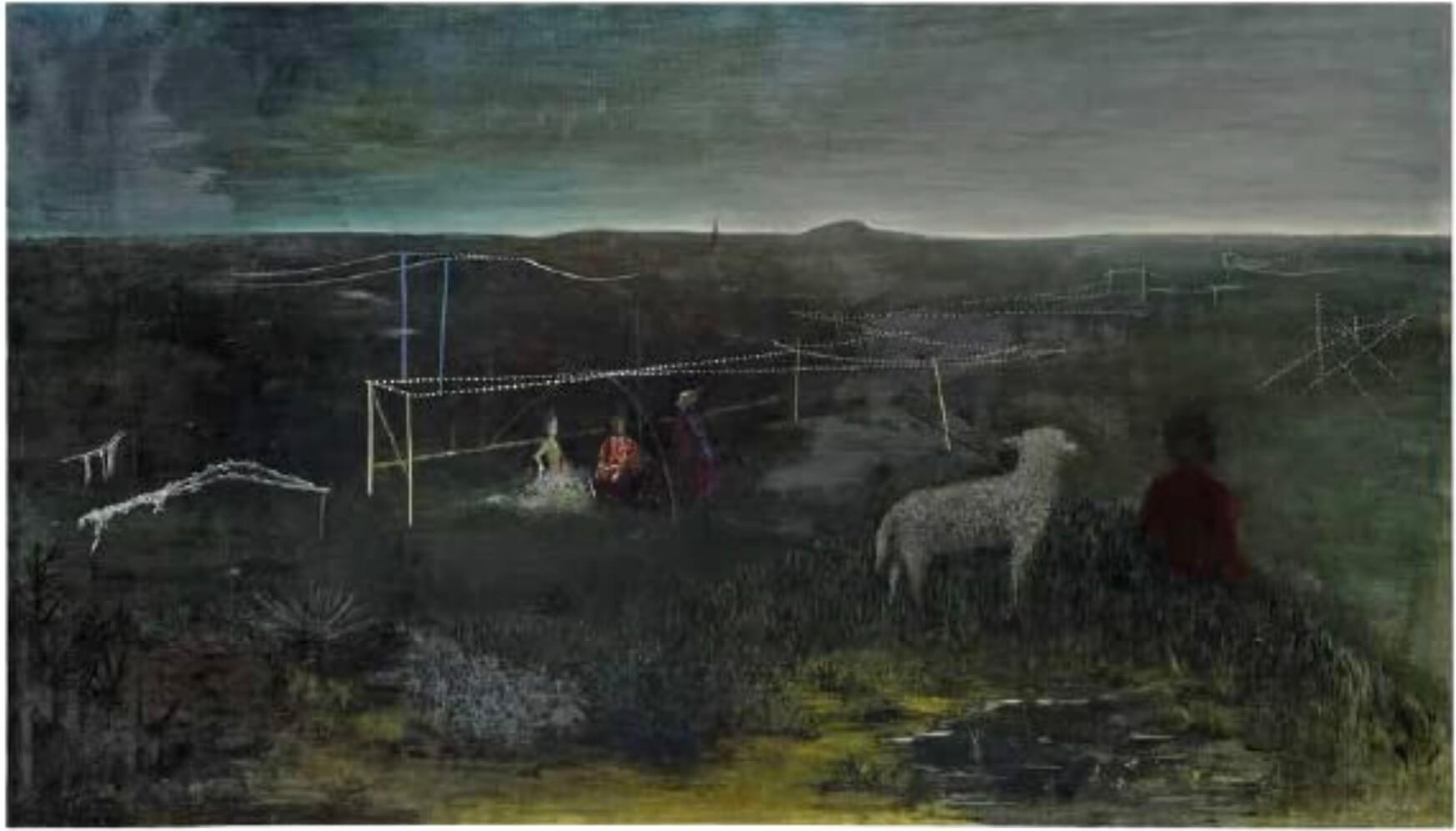

Oppenheim destroyed much of the art she produced during her depressive period in Basel, so it’s hard to say exactly what themes haunted her during this time. Only one of the pieces in this portion, a 1943 oil painting titled War and Peace, deals obviously with the war. In it, festively costumed figures sit amid an idyllic pastoral scene at the edge of the border demarcated by twinkling lights; on the other side, red-tinged darkness looms.

But despite the obvious influence, Oppenheim did not assign this depressive period to fear or war or even separation from her colleagues. “This crisis was actually a crisis of self-confidence,” she said, instead. “The whole patriarchal world fell on my neck.”

And it is this resistance to outside definition that is key to understanding Oppenheim’s work, which otherwise can feel dizzyingly wide-ranging. Oppenheim stubbornly refused to allow Jewishness to define her, even when it clearly impacted her; so too she resisted so many attempts at categorization.

As a young artist in Paris, Oppenheim broke off her affair with Max Ernst to protect her own creativity, loath to be known as a mere muse for an older, more famous artist. Later, she left surrealism behind entirely, cutting ties with Bréton and moving into a younger, Swiss scene dominated by pop art. She even, repeatedly, rejected her own fur teacup, saying it limited her and calling questions about it “boring” in an interview shown at the end of the MoMA exhibit.

Perhaps Oppenheim’s forced exodus from the Parisian scene was, in a way, a boon, allowing the artist to define herself, far away from the looming influence of Bréton or Ernst.

Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition is a confusing experience; there’s no cohesive style to speak of, few repeated themes, and the wall text offers sparse biographical details. (For example, Wolfgang La Roche, Oppenheim’s husband, for nearly 20 years, is mentioned only once, in passing.) Major events in her life — such as fleeing the Nazis — seem to barely make a mark. We can’t tell what impact they had, or didn’t.

Perhaps that is the overarching theme of her life and work: Oppenheim labored to be an enigma. She succeeded.

“Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition” is on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from Oct. 30, 2022, to March 4, 2023.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO