Yes, this woman really did make the greatest film of all time. Next question?

Chantal Akerman’s ‘Jeanne Dielman’ was recently enshrined by the BFI ‘Sight and Sound’ poll. Rightly so.

Chantal Akerman in 2004. Photo by Getty Images

Chantal Akerman’s 1975 masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles was declared the greatest film of all time in the prestigious British Film Institute’s “Sight and Sound” poll, to the surprise and delight of many of us known Aker-stans, surpassing perennial favorites (and deserving recipients to be sure) Citizen Kane and Vertigo.

Before her death in 2015, Akerman had lain on the margins of the “World’s Greatest” lists for decades as a respected and known quantity, like an influential but underselling indie-rock outfit. She was a film student favorite, as I wrote previously in this publication, and “generations of young filmmakers have embraced her as their own despite (or because of) her lack of marquee fame, which is all the more surprising considering her prodigious output and influence.”

So this selection was unexpected but eminently deserved. What was most remarkable about it was not what is so different about Chantal Akerman from Orson Welles or Alfred Hitchcock; that she is a queer Jewish feminist radically independent filmmaker who interweaves those disparate strands throughout her work is apparent. But what Chantal shared with those celebrated auteurs is the component missing from much of our contemporary fare: a radical commitment to the idea of a certain kind of motion picture art.

Akerman is the hero the cinema needs now, at this moment of reckoning with destructive blind spots in our culture industry and also, at the risk of sounding dramatic, a moment when franchise-driven Hollywood fare has taken cinema to the brink of extinction.

The idea is that cinema, unlike other forms of audiovisual entertainment, contains all the tools to watch it within the film itself. You don’t have to know more than you have been told on the screen. The point is not to be swept away into a world as complex as our own, but to teach you to have someone else’s experience, to feel what it is to be another person even for a brief time. Cinema can’t be ruined with spoilers; it acts like a spell on the viewer, commanding their attention in the present.

Akerman’s films are about the experience of a phenomenon in time. You can’t read about them; you have to watch them.

Yes, of course it’s possible to understand the brilliance of Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles by simply reading almost any article on it. The film chronicles the life of a housewife through her daily household chores and her work as a prostitute with a taught comparative precision. Even with just that sentence, you could write a decent college essay on the film.

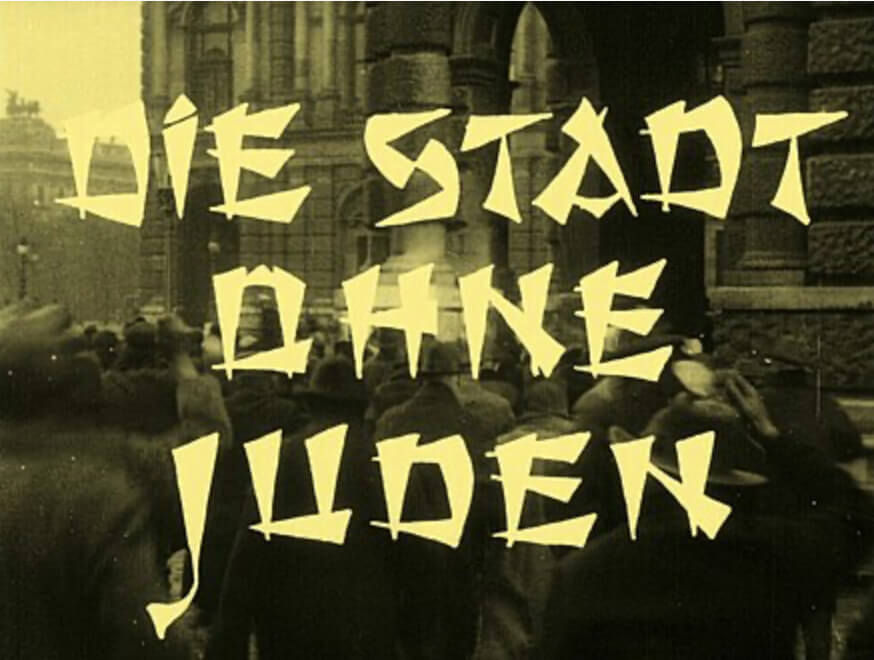

By watching two of the most famous clips, like the famous peeling of potatoes in one excruciatingly drawn-out sequence, or her welcoming of a john and putting his clothes up tidily on a rack, it is possible to understand her direct use of the male gaze and her brilliant inversion of it into a female gaze. It’s even possible to feel the alienation and loneliness that are the inherited experiences of her parents, both survivors of the Holocaust.

But by not watching the whole film (and preferably in one sitting) there is a lot to miss. What places her work over many of her contemporaries who came out of the late French New Wave conflagration is an attention to craft that equals a commitment to ideas.

In the minute-by-minute precision of Jeanne Dielman there is something of a trans-Atlantic element that speaks more to Hollywood than to Godard. There is something deeply Jewish about this in a different way from the inheritance of Akerman’s parents’ European Jewish trauma.

The American film industry welcomed lower- and middle-class Jews when many other vocations were closed off to them. They went straight from the junkyards to the studio lot. When the fine arts are reserved for in-groups, inspiration and genius can seem like the property of the elites. Craft is genius by other means. It is a celebration of repetition and wisdom, of tradition and adaptability. It is also unforgivably results-oriented. Does the object do what it intends to do?

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles weaves together different levels of craft, whether it is on-screen cooking or rituals around sex, into one experience that is itself rigorously seamless. It is exactly as long as it needs to be to make the point it requires.

This is why, even after her death, Chantal Akerman is a far better spokesperson than edgy-but-conservative cinephiles Quentin Tarantino or Martin Scorsese to speak up for cinema. Tarantino recently questioned whether there would be room for character-driven films in a world dominated by superhero mega universes. But this is a false choice. We aren’t choosing between Jeanne Dielman and Iron Man, nor are we choosing between a high-brow or a low-brow experience. We are choosing between a film that requires no preparation but demands your attention versus one that requires pre-knowledge of the rules of a universe and the creatures who dwell within: that is big enough to contain many narratives and spin in many directions.

Is it intended to expand your imagination or shut it down? You can’t have both; you can’t have your own ideas and experience someone else’s simultaneously.

I often joke that one of the best things about being a filmmaker in politics is that it’s much less political than the film world. With the many pressures and inputs to make this list it is not unthinkable to imagine a number of the 1600 judges will have only read about or seen the clips of Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. It feels a bit like a good one slipped through, under the radar, who can be our true champion.

And if the kind of pettiness about cinema seems above a figure like Chantal Akerman I would suggest you watch her films in wondrous real-time and get back to me.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO