How one Jewish woman’s crusade became the year’s most talked-about documentary

In ‘All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,’ artist Nan Goldin takes on the Sackler family

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” chronicles Nan Goldin’s history as an uncompromising artist and a crusading activist. Photo by Participant Media

Laura Poitras’ “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” a documentary about the artist Nan Goldin and her crusade against the Sacklers, the pharmaceutical family largely responsible for the opioid epidemic, is not an easy film to write about.

Ever since I caught the film at the Venice International Film Festival, I’ve been struggling to understand, let alone articulate, what makes the film so grandly, epically powerful.

Winning the top prize

The film is only the second documentary to win the festival’s top prize, the Golden Lion (the first was Gianfranco Rosi’s “Sacro GRA” in 2013). And it is the second consecutive winner for a female director — last year, it was Audrey Diwan for “Happening” (based on the memoir by Annie Ernaux, who won this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature).

For me, the victory for “Bloodshed” felt like a confirmation of my visceral and immediate enthusiasm for the film, a passion not readily shared by many other journalists at the festival.

“Artists and activism are both really basic topics for documentaries, so a film really needs to find a new form to tell stories like that,” complained a German colleague of mine, who found the film so staid and conventional — aesthetically, structurally, narratively — that he left midway through, he told me.

True, there isn’t anything radically challenging or technically new about the film. Poitras doesn’t dazzle us formally, and the film’s David vs. Goliath story doesn’t contain anything like the live-wire excitement and intrigue of Poitras’ previous films, the Oscar-winning “Citizenfour,” about Edward Snowden and “Risk,” about Julian Assange. Instead, “Bloodshed” achieves its dramatic and emotional impact by stealth.

The film chronicles Goldin’s activities with P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), an advocacy group that the artist founded in 2017 after surviving a near-fatal overdose brought on by her addiction to Oxycontin, the blockbuster drug manufactured by Purdue Pharma, which was owned by the Sackler family.

Addicted overnight

In an article that appeared in the January 2018 issue of Artforum, Goldin described her addiction to OxyContin, which was prescribed to her in 2014, after a wrist surgery in Berlin. “Though I took it as directed I got addicted overnight,” she wrote. “It was the cleanest drug I’d ever met.”

“My life revolved entirely around getting and using Oxy,” she continued. “Counting and recounting, crushing and snorting was my full-time job. I rarely left the house. It was as if I was Locked-In. All work, all friendships, all news took place on my bed. When I ran out of money for Oxy, I copped dope. I ended up snorting fentanyl and I overdosed.”

P.A.I.N. had existed for a little over a year before Poitras got involved.

“My worry when [Laura] came on, was that I don’t have any state secrets to share,” Goldin, now 69, said in Venice at the film’s press conference.

Museum protests

One might add another worry. Films about activism often run the risk of being one-dimensional, even when not militantly preachy. In its early scenes — the only ones that my German colleague stayed for — the film indeed seems headed in that direction. It opens on March 10, 2018, with Goldin leading a few dozen activists into the Temple of Dendur, the large-scale archeological reconstruction housed in a wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art that was named for the Sacklers at the time.

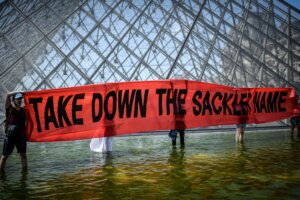

They shout slogans (“Sacklers lie, thousands die!”) and throw fake prescription bottles into the atrium’s pool before staging a “die-in.” It is the most spectacular of the demonstrations we see in the film, which also includes P.A.I.N.’s protests at the Guggenheim and the Louvre, designed to shame both Sacklers and the cultural institutions who accept the family’s ill-gotten money.

Removing the Sackler name

Largely as a result of Goldin’s activism and advocacy, many leading museums and art collections have removed the Sackler name from their walls. Some have even refused their donations; at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Goldin made her participation in a 2019 exhibition conditional on the museum rejecting a million-pound donation.

This story of an artist successfully wielding her influence as a cudgel against a powerful dynasty who used cultural philanthropy to distract from their “empire of pain” (the title of New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe’s 2021 book about the Sacklers) would make for an inspiring hourlong special on PBS. But Poitras is up to something far more challenging and ambitious.

Goldin’s work with P.A.I.N. is only one thread in this film’s tapestry. Parallel to charting the group’s chutzpadik protests and legal activism, Poitras fashions a portrait of Goldin’s life and career — another undertaking not without its potential pitfalls. Documentaries about artists, especially living ones, are often so in love with their subjects that they fail to critically engage with and illuminate their work. Poitras’ great conjuring act here is how seamlessly she welds together two documentary genres that, on their own, often slide into propaganda or curdle into sentimental mush.

Chronicling counterculture

What starts out as a film about a scrappy campaign to get plaques taken off museum walls becomes a sweeping examination of Goldin’s 50 years as an artist who chronicles underground subcultures, artistic countercultures and figures who inhabit the margins of society with unsparing frankness and deep sympathy. What emerges from the confrontation between Goldin’s art and her activism is their common source and origin: addiction, be it to substances, sex, violence or self-destruction, and the struggle to overcome it.

Poitras and her editors do a masterful job of keeping the film’s various poles in equilibrium until at some point, late in the film, they suddenly converge. The effect is all the more powerful for how it sneaks up on you. When it lands, it does so with the force of an epiphany.

The title of the film is grandly poetic and ambiguous. Are we to take it as a description of Goldin’s best-known work, including the photographic slideshow “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency”? Or does it describe the Sacklers’ practice of “toxic philanthropy and the whitewashing of blood money in museums and institutions,” as Poitras put in at the Venice press conference?

Losing a sister

The phrase “all the beauty and the bloodshed” comes, in fact, from a doctor’s report about Goldin’s older sister Barbara Holly, who was institutionalized as an adolescent. Goldin idolized her older sister, who at the age of 18 took her life by lying down in the path of an oncoming train near Silver Spring, Maryland. After the suicide, Goldin’s mother (who, according to one of Barbara’s doctors, seemed to require psychological care more urgently than her daughter) came across a handwritten note by Barbara with a passage copied out from “Heart of Darkness.”

“Droll thing life is — that mysterious arrangement of merciless logic for a futile purpose. The most you can hope from it is some knowledge of yourself — that comes too late — a crop of unextinguishable regrets. I have wrestled with death. It is the most unexciting contest you can imagine.”

This tragic family history, which Goldin previously explored in a 2006 exhibition called “Sisters, Saints & Sibyls,” forms the film’s third node, alongside her art and activism. It taps into the melancholy at the heart of Goldin’s work and ultimately makes the film into something infinitely richer and more universal than a mere report about a crusading artist and her boundary-breaking work.

Having introduced the trauma at the heart of Goldin’s suburban middle-class Jewish upbringing, the film follows her to New York, where she moved at 24, living in a loft on the Bowery and working at a Times Square bar called Tin Pan Alley that was a haven for a cross-section of the city’s outcasts.

Countering aesthetic norms

The connective tissue between these formative experiences, which she documented with a quick and dirty honesty that was thoroughly out of keeping with prevailing aesthetic norms about “art photography,” and her contemporary crusade against the Sacklers, is “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing,” a 1989 exhibition curated by Goldin of artistic responses to the AIDS epidemic that was decimating her community of artists and friends.

A controversy ensued after the National Endowment for the Arts rescinded a $10,000 grant to Artists Space, the downtown venue hosting the exhibition, because it refused to fund obscene art.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” delves deep into the themes of dependency and addiction central to Goldin’s work and suggests that these subjects are rooted in Goldin’s childhood and later fired up her creativity and her social engagement. But it is also a film of delicacy and beauty. In particular, Poitras paints a vivid and memorable portrait of the artist by mixing archival footage and candid contemporary interviews with Goldin’s photographs and slideshows.

There is much about “Bloodshed” that feels timely and even urgent. At the same time, though, it manages to transcend the specifics of the opioid crisis and P.A.I.N.’s crusade against the Sacklers and to communicate something essential about the power and meaning of art. Ultimately this elegant, haunting and brave film articulates the vision for the “Witnesses” exhibition laid out by Goldin in 1989. “I am not at all concerned here with art as a commodity,” she wrote in the catalogue, “but as an articulation, as an outcry, and as a mechanism for survival.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO