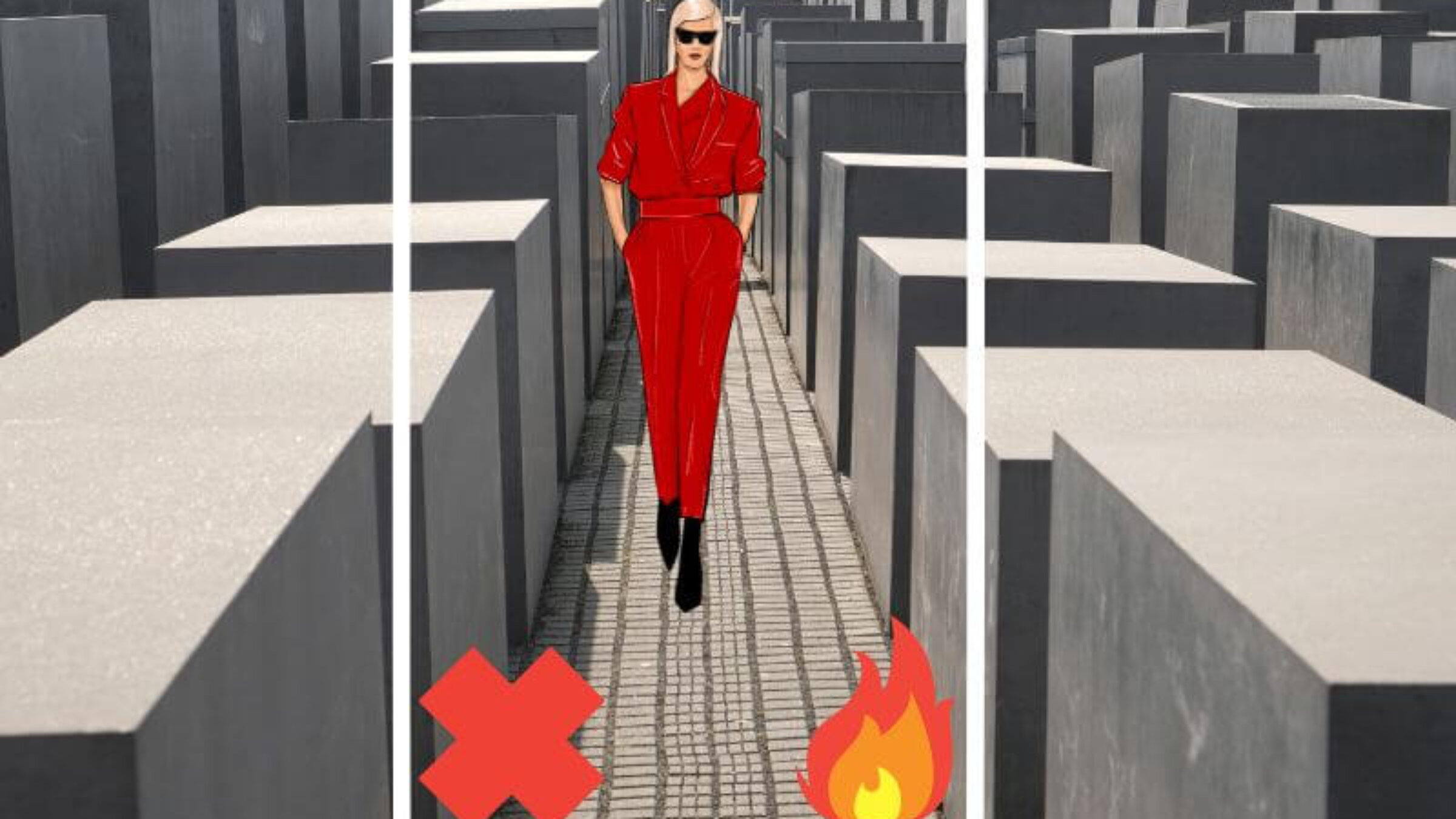

People are taking sexy Tinder profile pics at Berlin’s Holocaust memorial. Should we really be outraged?

A compilation of dating profiles featuring the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe has gone viral

Are people finding love at the Holocaust memorial? Graphic by Mira Fox/Getty Images

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is an imposing piece of public art. Dominating a square in central Berlin, the statue fills a 200,000-square-foot field with black, coffinlike stone pillars. Its orderliness evokes the precision of the Nazi killing machine. Its uniformity emphasizes the banality of the evil executed by the concentration camps. Visitors wander its narrow passageways, disoriented and overwhelmed.

And some of them, apparently, feel a little flirty.

At least, that’s the only explanation I can see for the fact that the Berlin Holocaust memorial is a popular backdrop for Tinder profiles.

A photo compilation of Tinder profiles went viral on Twitter and Reddit last week, showing dozens of women posing at the Holocaust memorial. Some of the photos are artistic, carefully composed shots of people looking soulfully into the distance. In others, the subjects grin, sit cross-legged on the pillars, do parkour or strike a careful pose.

berlin tinder is wild pic.twitter.com/Xzi9dWhF6K

— francis wolf (@francisxwolf) November 10, 2022

It’s nothing new. There are countless articles on the phenomenon, along with joking social media pages that round up Holocaust selfies at concentration camps and museums; artists have leveraged the phenomenon into edgy projects. Even the viral post about Tinder is four years old; it just got reposted.

Which raises the question: Is it still happening?

The Tinder trials

Last week, I reopened my defunct Tinder profile and got on Passport, a feature which allows users to to match with people in another city or country. (This is a premium, paid feature; usually the app only lets users see or match with people up to 50 miles away.)

I swiped through profiles for hours, trying various settings to change who the app showed. First, I just swiped as myself — a 31-year-old woman — which allowed me to see men and women interested in dating women.

But after about an hour, I didn’t see any Holocaust memorial pics, which made me wonder about the gender dynamics of the Holocaust thirst trap. Straight men are generally less likely to have carefully posed photos, and queer women are often more political — and thus, perhaps, tactful enough to avoid posting a pic at a memorial to murdered Jews.

I changed my profile’s listed gender so I would see straight women and queer men. But after an hour of swiping, all I’d learned was how German sex workers advertise. I saw plenty of other tourist attractions go by, both in Berlin and beyond: the Brandenburg Gate, the Eiffel Tower, even Petra — which I’d categorize as a more advanced, harder to get to tourist site. But only once did I see a woman sitting among the iconic black slabs of the memorial.

Well, I thought, as a D.C. native, I have nary a picture from my entire life of any of the monuments. So I transported myself to other cities. I swiped through London, Rome and finally Prague, which produced one profile of a man leaning in the dark pillared passages of the memorial. (As of this writing, neither of my Holocaust memorial baes have matched with me.)

Perhaps people saw the post and took their Holocaust photos down, or maybe Holocaust education has really improved in the past few years and they felt guilty. Or perhaps people are posting tons of Tinder profiles with the memorial, and I simply didn’t see them. A few hours of virtual jet-setting is hardly equivalent to the volume of profiles you see when you’re actually single, swiping daily in the hopes of finding true love (or at least a one-night stand).

But even if people have mostly stopped putting their Holocaust memorial selfies on Tinder, they’re still taking them — and posting them on Instagram.

“Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,” each person must type, in full, so their posts can join the tens of thousands of photos under the tag. They range from solemn to silly; some are only a few days old. An entire field trip of girls, who crammed into the narrow passageway, grin and stick out their tongues. A woman with lip injections and bared cleavage pouts at the camera. Even the posts with solemn captions about the Holocaust are carefully calibrated to make their subject look hot — while also appropriately serious.

Is it really so bad to post the Holocaust memorial on Tinder?

The comments, on both Twitter and Reddit, on the Tinder compilation, are divided. Of course, many people are horrified, and call the Tinder profiles disrespectful. They point out that there are signs around the memorial forbidding noise, jumping and climbing, pets, drinking and smoking, and bicycles.

But many note that the architect of the Berlin memorial, Peter Eisenman, knew that people might not always approach it in a somber fashion. “People are going to picnic in the field. Children will play tag in the field. There will be fashion models modeling there and films will be shot there,” he said in a 2005 Der Spiegel interview for the monument’s opening. “What can I say? It’s not a sacred place.”

(Eisenman’s description of the project on the memorial’s site, on the other hand, says the memorial should cause visitors to feel “a persistent state of reflection and contemplation” and “a disturbing personal experience.” It might not be sacred in the traditional sense, but it is meant to be powerful, affecting and, well, negative.)

When you come to @AuschwitzMuseum remember you are at the site where over 1 million people were killed. Respect their memory. There are better places to learn how to walk on a balance beam than the site which symbolizes deportation of hundreds of thousands to their deaths. pic.twitter.com/TxJk9FgxWl

— Auschwitz Memorial (@AuschwitzMuseum) March 20, 2019

The Berlin memorial is not the only place where people seem more focused on striking a pose than honoring the history. Auschwitz selfies are so common that the Auschwitz Museum had to issue a tweet asking people to stop posing for artsy photos on the railroad tracks that brought in trains full of Jews to be gassed. A now-defunct Hebrew Facebook page, called “With My Besties at Auschwitz,” rounded up selfies at a number of concentration camps, largely featuring Israeli teenagers on school trips. People selfie at the 9/11 memorial and Pearl Harbor. They pose with the Vietnam Memorial. They even take selfies at funerals — pretty frequently, actually.

And the selfies and thirst traps hardly seem any worse than the many political photo-ops that take place at the memorial. Those ones are certainly engaging with the history of the Holocaust — but doing so to leverage it in the pursuit of power. Isn’t the irony of using a monument to murdered Jews for propaganda more insulting than obliviously doing a high-fashion strut down its corridors?

It’s hard to say how to appropriately engage with death. The Holocaust, of course, is not just any death. It’s more brutal, more industrial, bigger. But it’s still hard to know what to focus on. The brutality of the Nazis or the resistance of the Jews? The sorrow for those lost or the joy of the lives they did live? Should we look to the future or focus on the past?

Memorials are not museums. They’re art, not history; they’re meant to evoke emotion, not transfer information. Perhaps people feeling sexy at the Holocaust memorial are missing the point. Or perhaps the way to engage with the memorial over time has changed.

“‘Selfies’ are a part of today’s cultural experience and the virtualization of the world,” Günter Morsch, the former director of the Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museum, told ABC. “In the virtual world, people try to integrate an authentic place into part of their own image and that’s actually something positive.”

The Israeli teens posing with their national flag at Holocaust sites may be smiling, but the message is clear: They can smile and pose at Auschwitz because they see themselves as forging a new, proud Jewish future. Even Eisenman said that he imagined the stones of his memorial might someday be seen as “foundation stones for a new society.”

Life moves forward after tragedy. People continue to jump and climb and run, and yes, to date.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO