How the Groucho Marx Halloween mask became ubiquitous

The significance of ‘Groucho glasses’ goes way beyond their cigar-chomping creator

The signature Groucho look dates back to 1921 when Groucho Marx first painted a mustache on his face. Photo by Istock

This Halloween, whether you attend an all-out costume party or stay home waiting for the neighborhood trick-or-treaters, you’re almost guaranteed to see a Groucho Marx mask. It may not be the most creative costume you’ll see, but it’s probably the most ubiquitous — and one of the most Jewish too. The one-piece nose and spectacles, known as “Groucho glasses,” have been around since the 1930s and it would be fair to call them the most iconic mask of modern times.

Like the Marx Brothers themselves, they’re timeless, unpretentious and as instantly understood as a whoopie cushion. Forty-five years after Groucho’s death, the mask has transcended its cigar-chomping Jewish namesake and creator. In 2020, it cemented its place in modern daily life when it became an emoji, a status that not even Frankenstein has achieved.

A longtime gag gift and children’s party favor, the Groucho mask doesn’t have the subversive overtones of a Guy Fawkes mask, the glamor of a Venetian carnival mask or the history of the tragedy and comedy masks of Greek theater. Rather, the big nose and fake mustache have long been a symbol of slapstick comedy or a lazy disguise.

Still, ever since Groucho first loped on the stage with his signature slouched strides, critics have teased out deeper meaning in the Marx Brothers’ antics. Since The New Yorker started publishing in 1925, the magazine has repeatedly discovered an overarching philosophy within the Brothers’ comedic anarchy. And for decades, scholars have considered Groucho to be the epitome of Jewish humor, full of irony and self-deprecating one-liners.

The mask that defined Groucho has always been part of this discourse. However, Groucho no longer defines the mask. Younger generations who have never seen “A Night at the Opera” or “Animal Crackers” still wear the glasses, nose and mustache and tack on “Asking for a friend [![]() ?]” to an embarrassing question on Twitter. The Groucho mask has taken on a life of its own, without Groucho behind it.

?]” to an embarrassing question on Twitter. The Groucho mask has taken on a life of its own, without Groucho behind it.

The Groucho mask’s origin story

The mask, of course, originated with Groucho. Born in 1890, Julius Henry Marx was the middle child of the five sons of a German Jewish mother and an Alsatian Jewish father. Growing up on East 93rd Street in Manhattan, the bookish Julius dreamed of becoming a doctor, but his mother, Minnie, inspired by her brother’s success in vaudeville, pushed her sons into show business.

Young Julius was forced to leave school at the age of 12 and found his first success on stage as a singer in 1905. Within a few years, the brothers developed a touring vaudeville act that lampooned a high school classroom. As was popular at the time, each brother played a different ethnic stereotype.

This early act gave Chico his affected Italian accent and Harpo his curly red wig, which started as part of his “Patsy Brannigan” costume. Harpo, however, quickly lost the Irish brogue and performed the part mute.

Groucho played a cigar-smoking Teutonic school teacher, Mr. Green, using a German accent, perhaps inspired by his own relatives. When the United States entered World War I, audiences began to boo the German character. Groucho quickly dumped the foreign accent and adopted what has been called a sing-songy Jewish cadence. His stage persona became that of a quick-witted hustler.

Groucho’s evolution mirrored America’s changing perception of Jews, from accented foreigners to fast-talking New Yorkers.

In 1921, the Groucho look took full form. According to Gary Giddins, who wrote about Groucho’s mask for The New York Times in 2000, the Marx brother was running late to the theater after his son’s birth. “Having no time to glue on whiskers, he painted a mustache with greasepaint,” Giddins recounted.

The slapdash makeup got laughs, but the theater manager insisted the audience deserved a “real fake mustache.” Groucho, however, stuck with it. For an audience accustomed to vaudeville performers painting their faces black to demean others, Groucho used black paint to poke fun at himself.

When the brothers made their first movie, “The Cocoanuts,” in 1929, director Robert Florey objected to Marx’s amateurish disguise

“Florey demanded a genuine mustache, arguing the audience wouldn’t believe a painted one,” Giddins wrote.

“The audience doesn’t believe us anyhow,” Marx responded.

In “The Cocoanuts,” the Marx Brothers orchestrated a comic assault on social conventions and hierarchy, but the crude fake mustache mocks filmmaking itself. Just two years out of the silent era, Paramount Studios’ big budget production was undermined by the cheaply drawn on mustache and eyebrows. This proved to be part of the comedian’s success. By not believing Groucho’s mustache, the audience was in on the joke.

In the 1933 movie “Duck Soup,” the power and simplicity of Groucho’s get-up becomes clear. In one scene, both Harpo and Chico slide on glasses and apply black paint to their face, instantly becoming Groucho clones. The resemblance is so convincing that Harpo plays Groucho’s reflection in a mirror.

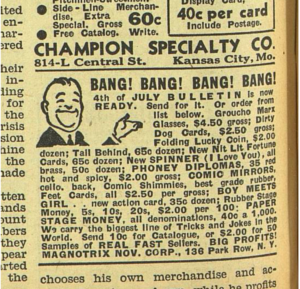

Soon after, anybody could perform the same trick at home. A New York wholesaler, Magnotrix Novelty Corp., first advertised “Groucho Marx Glasses” in Billboard magazine in 1936. They later shortened the name to “Groucho Glasses.” At the same time that anyone could transform into Groucho with the set of glasses with nose and mustache, the movie star could do the reverse. By removing the grease paint, a clean-shaven Julius Marx could walk the streets unrecognized at the peak of his fame.

‘We never denied our Jewishness’

As the popularity of the Marx Brothers waned in the 1940s, Julius grew a real mustache. The middle-aged bushy-eyebrowed comedian became a caricature of himself, blurring the lines between his off- and on-screen personas as his face took on the Muppet-like look of Groucho.

Marx found fame once again as the host of the game show “You Bet Your Life.” First on the radio for three years and then on television in 1950 for 11, with cigar in hand, he became a staple of postwar pop culture. This opened the door to merchandising opportunities. A 1954 board game based on the TV program came with toy glasses, mustache and cigar. Likewise, came official Marx-approved “Groucho Goggles

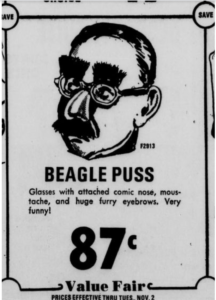

Groucho’s cartoon-like features became a commodity. Fans could purchase any number of knockoffs with names like “Schnozzola” and “Beagle Puss,” but the official “Groucho Goggles” came with googly eyes and a fake cigar attachment. Whether branded with his name or not, the masks made Groucho the face of comedy. That he was Jewish wasn’t lost on anyone.

Ruth R. Wisse, professor of Yiddish literature at Harvard, chose a Groucho mask as the image for the cover of her 2013 book, “No Joke: Making Jewish Humor,” even though the star’s one-liners and double-entendres rarely contained Jewish references.

“We Marx Brothers never denied our Jewishness,” Marx said. “We simply didn’t use it. We could have safely fallen back on the Yiddish theater, making secure careers for ourselves. But our act was designed from the start to have a broad appeal.”

The Groucho mask lives on without Groucho

Cultural critic Lee Siegel suggested that the Marx Brothers’ decision to not rely on their Jewishness was “partly the result of the antisemitism that was rampant at the time, easily accommodated by the Jewish moguls who ran Hollywood.” In his 2015 book, “Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence,” Siegel dissected Marx Brothers’ movies, and argued that Groucho, as an eternal outsider and iconoclast, defined Jewish humor, citing his influence on Jewish comedians like Lenny Bruce, Woody Allen and Sacha Baron Cohen.

Certainly, Groucho’s conversational style, timing and truth-telling jokes can be found in many modern-day comedians, both Jewish and gentile. However, the mask is Groucho’s most obvious legacy, even though it has detached from Groucho.

The emoji is called the “disguised face” without any reference to its creator. The glasses are almost never advertised with Groucho’s name. Perhaps a reflection of copyright law, it also shows that the funny disguise’s success is no longer tied to a star who peaked in the first half of the 20th century.

You don’t need to be a 1930s cinephile to enjoy the horn-rimmed glasses and thick mustache. Try them on any 10-year-old, and you’ll see the bit works without context, let alone the subtext academics have labored over. The mask’s comic effect is so universal and instinctive that a 1999 Psychology Today article about humor and therapy was titled “The Effect of Groucho Marx Glasses on Depression.”

If the Groucho mask has transcended Groucho, does it mean it also transcends his Jewishness? In truth, the Groucho glasses can never escape Groucho. The mustache and eyebrows may have been fake, and the eyeglass frames may have been store-bought, but the nose was always his.

Recently, a copy of Julius Marx’s 1922 passport application surfaced on Twitter. Always poking fun at authority, the comedian filled in his description facetiously. For the mouth, he answered, “pretty good.” He called the chin “normal. ” As for the nose that lives on in plastic form on masks around the world, he described it as “Jewish.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO