How a teenage photographer captured a vanishing world before the Holocaust

Richard Scheuer’s images of ordinary life in 1934 are both unsettling and prescient

A street scene in Warsaw captured by a young Richard Scheuer. Courtesy of Dan and Jonathan Scheuer

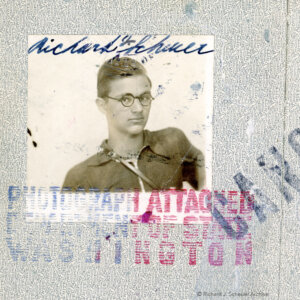

In 1934, when American-born photographer Richard J. Scheuer was 17, he went on a continental tour with his father and a 35 mm camera. He took black-and-white photos of ordinary people, often artisans and craftspeople, doing ordinary things, just living their lives.

The photographs, taken in such locales as the Basque region, Budapest, Sarajevo and Warsaw, focused on Jews working, socializing or doing nothing of consequence. The Warsaw photos are especially unsettling as we look at their subjects’ unknowing faces through the prism of hindsight — it was only five years before the apocalypse.

Scheuer’s photos, now on display at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in an exhibit entitled “Street Visions,” are bold and fresh and unabashed. Unlike much portraiture of the era nobody is posed. His attention to physical details, personal gesture and expression as well as his use of natural light are all noteworthy.

Regrettably, Scheuer. whose work seems to anticipate Robert Frank and Gary Winogrand, never became a professional photographer, although he was a hobbyist for the rest of his life; indeed he had a darkroom in his home in Larchmont, New York. In later years, his photographs centered on family.

Forgotten photos

After he returned from his trip abroad, he developed the negatives and contact strips, but never had them enlarged. They were stored away in a cardboard box and placed in the back of a closet.

Life went on. He finished high school, got an undergraduate degree at Harvard, and later served as an officer in the Army Signal Corps during World War II.

He launched an impressive career in real estate and was known for his philanthropic work, serving as board chair at the Hebrew Union College.

In the 1990s, when he and his son Dan were cleaning out a closet, they came upon a cardboard box housing the old negatives and contact sheets, some curled together, brittle and crumpled with age. Dan had no idea they even existed until that moment and when he suggested they might try having them developed, Scheuer was not interested.

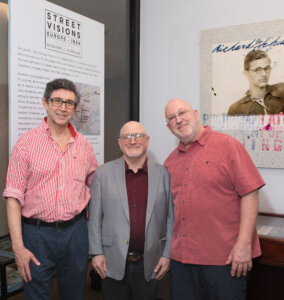

“There are many theories for that, but it’s all speculative,” said Dan Scheuer, who spoke with me at the exhibit along with his brother, film and music producer Jonathan Scheuer, and their life-long friend Charles Seton, an archivist and photo restoration specialist, who played a major role in pulling the exhibit together.

“There may be some bad memories attached to those photos that we don’t know about,” said Dan, who is a photographer in his own right. “And, of course, realizing what happened afterwards might make him not want to revisit those shots. And, it may be that he was just very modest. He never thought of himself as an artist.”

The restoration project

In 2008 after Scheuer died at 91, Dan wondered about those photos just lying there, gathering dust. He regretted that he didn’t know more about his father’s photographic journey and decided to have the negatives digitized and restored.

“We were worried the negatives would crack,” said Dan. “Many were not salvageable.”

“We didn’t know if they would crumble and burst into flame,” added Seton. “We found a professional conservator that mostly handles silent movies and they took care of it.”

Determined to enhance the immediacy and authenticity of the shots, while avoiding the reflective glare of glass, the prints are matted but not framed, explained Seton, who tried to remain true to Scheuer’s vision. It was largely a matter of adjusting the light and removing defects, such as a hole in the negative, which he was able to repair.

The restoration was a massive endeavor, but it was only the first step. They also had to identify photographic locations, reconstruct the chronology of the trip, and research a host of other questions. Forty photos made it on to the walls of the exhibition.

Engaging with his subjects

“What’s so striking to me is the direct engagement between subject and photographer,” Jonathan Scheuer told me as we walked through the exhibition. “We were surprised and thrilled with the level of Dad’s engagement. The man that we knew was more shy, less apt to put himself out there. In later years he shot the backs of people. He was never so bold and adventurous again.”

I asked the brothers about his artistic influences, and they admitted they don’t know if he ever formally studied. He may have read books on photography and visited galleries and may have even been familiar with the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who was notable for his spontaneous street scenes along with his patterns of light and shade. But no one can say with any certainty.

I asked about his politics, and how that may have influenced his choice of subjects.

“He was interested in working people,” said Dan.

“He was not ideologically leftist,” Jonathan added, “but he was drawn to people who made things with their hands. He saw the dignity of the ordinary person, no matter how tattered. Look at that picture.”

He pointed to “Man with Fez,” a shot taken in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia. “His jacket is disintegrating,” Jonathan said, “Yet there’s so much dignity in his face.”

The brothers told me that that their father was culturally Jewish, identified as a Jew, and was interested in the continuity of Jewish life and its history, certainly more so than its theology. Either way, the Eastern European Jewish world, one step away from the shtetl, was far removed from his own comfortable German Jewish Manhattan origins. His four grandparents were born in America.

Unsettling shots

One of the more unsettling Moscow photos, “Official Proceeding,” captures a tribunal of some sort, where Lenin’s picture hangs ominously on a wall. There’s no way of knowing what was happening when Scheuer took the photograph, but Seton pointed that, given the angle of the shot, his camera was at waist level and in all likelihood concealed.

Perhaps the most unnerving shot is “Livery Driver,” taken in Warsaw and evoking, almost presciently, the expression and posture of a Nazi guard. The man stares directly into the camera, his eyes dead.

Clearly, in these pre-war years the subjects of Scheuer’s photos could not anticipate what was coming. Still, the faces in most of the pictures, belong to people who’ve already witnessed and experienced the darker aspects of Jewish life, none more vividly than “Man in Train Station.” Taken in Warsaw, this is a remarkable portrait that captures a lifetime of complicated emotion. There is nothing innocent in that face.

“The poignancy and pain of Warsaw is a given,” said Jonathan, But it’s important to see the whole trip, the beauty of the photography as art, how the life of one person can be apprehended in a single photograph. I hope viewers can immerse themselves in that artistry.”

“I believe if my father could see this exhibit he’d be happy with it,” said Dan. “Especially since it’s on display at HUC. Our 101-year-old mother saw it and it loved it.”

“Street Visions: Europe, 1934 — Photographs by Richard J. Scheuer” is showing in the Backman Gallery at the Dr. Bernard Heller Museum at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, through Dec. 15.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO