Indisputably, a Jewish genius — but also a pariah and a bumpkin

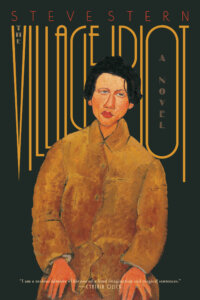

Steve Stern’s ‘The Village Idiot’ fictionalizes the life of the Belarusian painter Chaim Soutine

Visitors to the Sotheby’s galleries look at a 1921 painting by Chaim Soutine entitled ”L’Homme au Foulard Rouge.” Photo by Getty Images

The Memphis-born American Jewish novelist Steve Stern, 74, has long been inspired by Jewish folklore and a dream-like Yiddish literary tradition in the vein of I. L. Peretz, Itzik Manger, and Lamed Shapiro. Author of “Lazar Malkin Enters Heaven” and “The Frozen Rabbi,” Stern has just written a new book, “The Village Idiot.” A fictionalized life of the Belarusian Jewish painter Chaïm Soutine, the book contains reveries and offbeat humor. Recently I spoke with Stern about how Soutine’s Jewish identity was infused in his art.

The art historian Avram Kampf described Soutine’s paintings as “filled with nervousness, anxiety and fear. His work was believed to mirror the situation in which all European Jewry found themselves in the period between the wars.” Yet your novel suggests that the Yiddishkeit in his imagery was also positive, reflecting strength, not just angst, right?

Yeah, I had a sense that Soutine was fleeing the shtetl his entire life, unlike Chagall and [Emmanuel] Mané-Katz and other Jews in the School of Paris who had fled Eastern Europe. Soutine doesn’t include a single Jewish image in his work, and maybe I’m projecting this, but I wanted him to be followed by the shtetl, in a way that made the folklore and superstitions of the world that he fled inescapable.

The Kabbalist Henri Sérouya stated that Soutine’s paintings are troubling because they are “permeated with the vehemence of Jewish mysticism.” Would you agree?

Well, I think Soutine would emphatically disagree. He was virtually unschooled. He had been a cheder-bocher [schoolboy] like every other kid in a backwater shtetl. He came from an excessively impoverished environment and left at age 16. His Jewish education was pretty much limited to the aleph bet and he wouldn’t have been aware of much in the way of traditional Jewishness or Kabbalah. But the character I depicted embodied a lot of knowledge absorbed by osmosis.

In your novel, the Lithuanian sculptor Jacques Lipchitz calls Soutine the “shtot meshugenah, the village idiot.” Soutine must have had considerable mental alertness to avoid arrest during the Nazi Occupation of France, no?

Soutine was a genius and the work is extraordinary and experimental and avant-garde in many ways but the man himself was uncivilized. He was basically a bumpkin. He had a personality that offended almost everyone he knew. He smelled bad and was afraid of plumbing. He was a pariah in the village he came from, as his making of images was a violation of the Second Commandment. The term village idiot was used ironically by Lipchitz, but wasn’t a terrible stretch when applied to Soutine.

At the end of the novel, when the dying Soutine sees his friend the Italian Jewish painter Amadeo Modigliani again, is this a form of transfiguration, a Yiddish parallel to the ending of Gustave Flaubert’s “A Simple Heart” where the protagonist sees a sanctified image of her stuffed pet parrot?

That was the closest relationship of his life. He worshipped Modigliani, and never turned against him as he did almost everyone else he knew. Modigliani was a mentor for him.

The novel’s opening scene presents Soutine in a diving suit, pulling a boat carrying Modigliani. It’s like a Marx Brothers slapstick comedy, and in some photos, Soutine slightly resembles Chico Marx. Given the exuberance in their lives, why are these two Jewish artists usually presented so grimly? The Swiss author Ralph Dutli wrote a novel entirely composed of Soutine’s tragic delirium when being transported to Paris for surgery before he died.

When we look back, there is a shadow over that whole period which finishes tragically. So many of the individuals involved had tragic fates. Maybe three quarters of the Paris School ended in [concentration] camps, but they didn’t know that was coming. In the teens and ’20s, there was a kind of vitality that you could extract comedy from. That’s why I wanted to give a sense of all of Soutine’s life occurring simultaneously with humor to redeem what was inevitably tragic about his life.

Although Soutine was in touch with the Yiddish writers Oyzer Varshavski, who would be murdered in Auschwitz, and Sholem Asch, he generally did not kvell in Jewish cultural groups. Why not?

Soutine’s taste in literature was Modigliani’s taste, as Modigliani had basically introduced him to books, and his basis was Dostoyevsky. No one could be more antisemitic than Dostoyevsky, so [Soutine] tried to shed Yiddishkeit, but I don’t think he did it very successfully.

You portray Soutine as escaping the shtetl, but rediscovering his Judaism in Occupied France. Apart from the philosopher Henri Bergson, didn’t most assimilated or converted Jews persecuted in Fascist Europe resent their origins even more bitterly, since they felt no affinities to a family past for which they were suffering? Why was Soutine different?

You know, I don’t think he was that different. To be honest, I wanted the shtetl to catch up with him and claim him as its own, to bring his history full circle. He didn’t deny his Judaism, but he resented those who he saw as exploiting it, like Chagall or Mané-Katz who used imagery out of Jewish folklore as a nostalgic exploitation of the shtetl. So this hostility to the past remained with him but his identity as a Jew became more emphatic at the end.

Was Soutine’s disdain for Chagall comparable to what you referred to in a 2007 interview as “Yiddishkeit lite” with a “kind of theme park mentality, wherein the Jewish past is presented in language and settings that evoke a sepia sentimentality, that defang a ferocious experience until it’s safe for nostalgia”? You were alluding to the American Jewish authors Nicole Krauss, Jonathan Safran Foer and Michael Chabon.

Right, sour grapes! (laughs) Soutine grew up in wretched circumstances and was punished for wanting to paint. There’s a savage, ferocious element to his work that comes directly out of his experience of the shtetl, with the shadow of the pogrom, the kind of persecution that would have defined much of the experience of growing up there. The East Europe of Chagall and Mané-Katz is pretty and magic, and violinists float in the air, and the fiddler on the roof is an icon. Soutine would not have accepted that kind of romanticization of the Jewish past.

The notoriously antisemitic author Roald Dahl included Soutine as a character in his 1952 macabre story “Skin.” In the tale, Soutine paints a portrait of a woman on a man’s back, which is then covered by a tattoo. Is Soutine suitable for the horror genre, or are the animal carcasses he painted misread as mere gory decay?

Soutine definitely had a kind of necrophiliac attachment to dead animals, but you could say the same thing about Rembrandt. All of Soutine’s paintings could be seen as an imitation of Rembrandt, whom he idolized. I always see a comic element to these images of oxen, chickens, and herrings, maybe because he was hungry all the time. The portraits, close to caricature, I don’t see as dark. But the landscapes seem to be happening in a maelstrom, with an internal turbulence.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $325,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO