In London, an antisemitism scandal has sparked a play about antisemitism. Is it helping?

The Royal Court Theatre’s response to a very public drama? Even more drama.

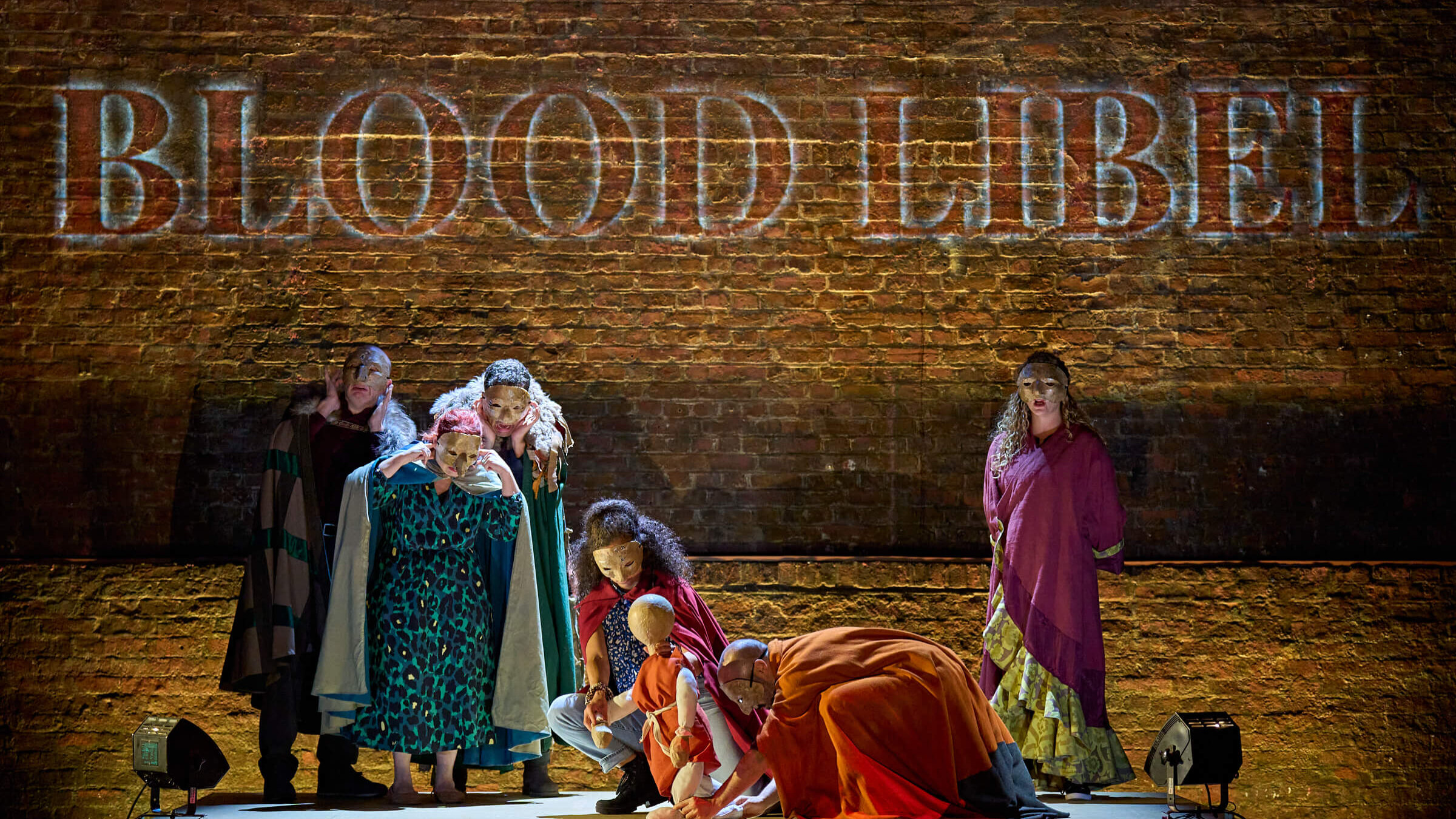

A scene from “Jews. In Their Own Words“ at the Royal Court Theatre. Photo by Manuel Harlan

LONDON — If you linger outside the Royal Court Theatre after a performance of Jonathan Freedland’s “Jews. In Their Own Words,” you’ll hear some ordinary post-theater chatter. Friends compare notes and ask after each other’s families. People discuss whether they ought to grab a drink.

But, almost inevitably, there’s also someone in the crowd speaking quietly, just to a friend, about the antisemitism they’ve experienced in their lives.

After one preview, a group of women in their 70s or 80s approached Freedland, 55, a journalist by trade. One embraced him. When she was 11, she said, she was playing a sport at school and scored a goal.

“Suddenly a girl, who she thought was a great friend of hers, turned on her and called her a ‘dirty Jew,’” Freedland said. “She hadn’t told that story before. Her friends — old friends — hadn’t heard it.”

After several years of bruising high-profile battles over antisemitism in the United Kingdom, Freedland said over an early dinner in Sloane Square, the posh West London plaza on which the Royal Court sits, he’s seen the play give Jews the sense of being in a space where it feels safe to “trade stories of antisemitism.” For some, like that older woman, that experience has proved “quite cathartic.”

That the Royal Court has become that space is, to put it mildly, surprising. In 2021, the theater sparked yet another of those very public antisemitism battles by mounting a play, Al Smith’s “Rare Earth Mettle,” in which the central figure was a power-hungry billionaire called Hershel Fink. The scandal was bad enough that the British government’s independent antisemitism adviser, Lord Mann, told the London-based Jewish Chronicle that he planned to boycott the theater.

Every cultural institution weathers scandals. The Royal Court knew the playbook for handling this one. “Normally, you know, it’s about an apology, and about some work, and a statement, and somebody goes on a course,” said Vicky Featherstone, the Royal Court’s artistic director, in an interview. The theater took all those steps. But it still didn’t feel like enough.

The result of that feeling is “Jews. In Their Own Words,” a piece of verbatim theater about the experiences of 12 British Jews with antisemitism on the left. It’s an unusual bit of self-reflective work, examining the failures of both the Royal Court and the political movements with which it has long been affiliated.

And while the play has meaningful flaws — one review called it a “muddled act of public contrition” — it has pushed both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences to think about British antisemitism in a new and possibly productive light. After one of the three performances I saw, I heard a woman give a capsule review to a friend as they walked to the Tube.

Yes, she knew about antisemitism, she said, but “I didn’t realize how permanent it was.”

‘Another Jewish billionaire trying to steal people’s land’

The Royal Court could have avoided the “Rare Earth Mettle” scandal. An accent coach who participated in a 2020 workshop of the play, which had been in development since 2015, raised the first objections to the idea of a character named Hershel Fink. The director, Hamish Pirie, told her that the character was modeled on Elon Musk, who isn’t Jewish; the matter was dropped.

Then, in September 2021, a Jewish director at another workshop expressed alarm at the depiction of, as he put it, “another Jewish billionaire trying to steal people’s land.” Still, the name stayed.

Then, the week before “Rare Earth Mettle” began previews in November 2021, the Royal Court sent out a marketing email describing the character of Hershel Fink as “messianic.” Within hours, a number of Jewish artists involved with the theater reached out with concerns. Social media chatter about the name, none of it flattering, picked up steam.

By the end of the day, the theater, now in crisis mode, made the decision to give the character the new name of Henry Finn. In announcing the change, it noted that he was not intended to be Jewish, or seen as such.

For Jews, it was obvious that the name “Hershel Fink” wasn’t just Jewish; it felt like a dog whistle, invoking the trope of the avaricious Jewish puppet-master without stating it. Hadley Freeman, a Jewish columnist for The Guardian, captured the sentiment in one wry tweet. “I guess the name Shylock Shlomo Liebergoldbergstein was already taken, huh,” she wrote.

The Royal Court is proudly leftist. For many in its orbit, it was exactly the theater’s principle of combating bias that made its apparent blindness around the stereotype of Hershel Fink painful.

The play opened as scheduled. But the scandal overshadowed its run — and, to some extent, the Royal Court’s whole season. The law firms Kirkland & Ellis and Weil, Gotshal & Manges, both significant corporate backers of the theater, declined to renew their funding. Some individual backers dropped out, too. Ticket sales for “Rare Earth Mettle” were anemic, an outcome, as the theater wrote in a February board report, that was likely “a direct result of this incident.”

“The theatre sets out to be exemplary in its artistic, social and cultural behaviors,” the board concluded. “In regard to ‘Rare Earth Mettle’ it fell short of those ambitions.”

‘There is no defense of not knowing’

As the scandal unfolded last fall, Vicky Featherstone reached out to Jonathan Freedland through a mutual friend.

Freedland writes a column in The Guardian, a paper with a left-leaning readership, in which he regularly engages with issues of British antisemitism. During a long conversation by phone, he told Featherstone he would have been “more forgiving” of the Hershel Fink saga “if it had happened five years earlier.”

Since 2015, when Jeremy Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party, the increasingly strained relationship between Jews, Labour and the left had been in the news almost constantly. The list of Labour-related antisemitism scandals from Corbyn’s five years as party leader is long and tortuous. The saga culminated with an external investigation that, in 2020, determined that the party under Corbyn had unlawfully failed to address claims of antisemitism.

The impact of those years on British Jews was clear. Labour had consistently drawn a steady if small voting base from British Jews, who make up less than 1% of the U.K. population. In 2019, in the final national election under Corbyn’s leadership, a poll found that 87% of British Jews believed that Corbyn was antisemitic. In the most heavily Jewish district in the country, Labour earned a meager 19% of the vote — a fraction of the 44% it snagged only two years earlier.

Hence Freedland’s point to Featherstone. After that tsuris, the ignorance about antisemitism the Royal Court had displayed was hard to forgive.

That was especially true, it turned out, because antisemitism on the left was, at the time of the Hershel Fink affair, an issue the theater was already deep in conversations about. A Labour Member of the House of Lords who sits on the theater’s board had asked, during the Corbyn years, if the theater might consider doing a play “about antisemitism in the Labour Party.” Shortly thereafter, the actress Tracy-Ann Oberman, an outspoken critic of antisemitism on the left and a longtime friend of Featherstone’s, approached her with the same idea.

The right approach, Featherstone and Oberman decided, was to construct a play out of the words of British Jews. But it was a long-term project. There wasn’t a sense of “radical urgency about it, like do it right-right now,” Featherstone said.

Then came the outrage about “Rare Earth Mettle.” Suddenly, what had been one idea on a long docket was a right-right now kind of item. “We were all very broken by the harm that we caused, and by our lack of understanding,” Featherstone said.

So she told Freedland that, in the wake of the scandal, the theater wanted to do something meaningful. They wanted to stop talking about the idea for this play, and actually make it. Would he write it?

Freedland was worried that the Royal Court only thought of the play as “a gesture to get them out of the PR hole” — an effort he was definitely not interested in aiding. And he knew that if he accepted the assignment, he’d face serious mistrust from the Jewish community.

But he found himself focusing on the fact that he’d spent years using his column in The Guardian to urge British institutions on the left to take concerns of antisemitism seriously. It was a charge they had often failed to meet.

Now, he said, “here was a pretty august institution of that progressive, cultural, liberal left doing exactly that.”

Plus, he thought: “if it goes wrong at any point, I will just walk away.”

‘I think it’s about, like, five types of Jews’

Two women were chatting in the roomy, warm bar in the Royal Court’s basement before a preview of “Jews. In Their Own Words.” They didn’t have tickets to the play. They had just met up for a drink and a bite.

But one of them was thinking about sticking around for the show. As she talked herself into doing so, her friend asked what it was actually about.

“I think it’s about, like, five types of Jews,” she said.

“Jews. In Their Own Words” isn’t categorical in quite the way she meant. But the idea of a “type” of Jew, or several types, is central to it.

The play’s actors depict a cast of characters including some famous British Jews, like the novelist Howard Jacobson, alongside more everyday sorts: a Haredi man with firsthand experience of the violence of antisemitism; a progressive social worker struggling with her colleagues’ tendency to look past bias against Jews; a Mizrahi Jew who does interfaith work with Muslim communities.

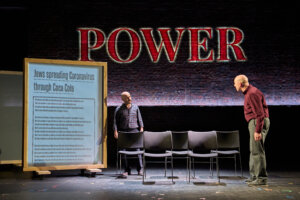

Things start off with a set of brisk showpieces, including a set of energetic pantomimes and a flamboyant song and dance set to the refrain “it was the Jews that did it.” Then it moves into a slower, more somber, conversational register. Longer and more challenging stories come out. The mood, initially a bit hectic, darkens.

The show ends with a gesture at resolution that feels, perhaps purposefully, incomplete: It leaves unanswered the question of what telling all these stories ought to achieve.

Some critics have accused the play of being overly didactic; one deemed it to be “basically a performed lecture.” That has more to do with its tone of sometimes overwhelming earnestness than its structure, which pulls off a more creative theatricality than its premise might suggest. Characters whose stories reflect one another are portrayed in conversation, although they’ve never met. At one touching moment that would be a shame to spoil, the all-Jewish cast breaks the fourth wall to address the audience directly.

The play has undeniably rough edges. In that, it mirrors the mindset of its makers, for whom British Jewish identity, personal and cultural, is a work in progress.

Audrey Sheffield, who co-directed the play with Featherstone, said she was drawn to the project because “my relationship to my Jewish identity was an area that I’ve been interested in exploring — that I have been much more in touch with over recent years.”

The environment behind the play, Sheffield said, felt very much like a Jewish “coming together.” It changed her sense of her Jewishness: It made her want to own that identity more publicly, and also “furthered certain questions that I have.”

Promotional materials for “Jews. In Their Own Words” frame the play as “a theatrical inquiry” into the antisemitism that inspired it. But there’s a deeper level of questioning in the play as well, not about dealing with antisemitism, but about being Jewish. How much should we let the politics around Jewishness affect our communal life? Is it possible to prevent hatred or ignorance from informing how we think of ourselves? Why does it sometimes feel so grating to talk about this identity?

If there is something strained and undecided about “Jews. In Their Own Words” it’s because there is something strained and undecided about the experience of being Jewish. That’s why the parts of the play that feel a bit, well, off are the ones that end up working best. The pantomimes; the kick line; the broken wall between cast and audience: They point to the fact that there is something inherently and uncomfortably performative about living as a Jew. There are points in most Jewish lives where we find ourselves assessing our audience to figure out if our Jewishness is safe to talk about, and if so, in what ways.

‘Maybe I’ve got sick of listening to antisemitism’

If “Jews. In Their Own Words” has one serious strength, it’s in its ability to generate the catharsis that Freedland hoped for — the kind he saw in the older woman finally telling her friends about the girl who yelled a slur at her in the schoolyard. It happened to me, too. After the first preview, a friend who attended the show with me asked what I’d thought. I found myself, without planning to, telling him about things I never talk about: names I’ve been called, times I haven’t felt safe.

Some of the people telling their stories after the show confessed, in nearly the same breath, that they didn’t like the play very much. I understood that, too. These stories can sound trite and overblown, in part because they’ve been told by someone, somewhere, so often.

But sometimes they do change things — if not the world, then how we see ourselves.

One night, I met a woman named Sarah Lou Morris, who was wearing one of the most colorful pairs of shoes I’d ever seen, in the crowd outside the theater. A few days later, we went for tea. Morris told me that before that week, she had never spoken up about antisemitism when she encountered it. She preferred, she said, to treat it with “removed interest.”

The day of Queen Elizabeth’s funeral, something changed. Morris, 71, was watching the proceedings at The Ritz. The man sitting next to her, a stranger, asked her to lunch. He told a story about his lawyer, who, he noted, was Jewish. There was no reason for him to bring that up, Morris thought. “I’m Jewish,” she told him.

He changed the subject. It wasn’t clear he understood that he’d been inappropriate. But she was shaken. It was the first time in her life that she had ever responded to something she saw as antisemitic, and she didn’t really understand why she’d done it.

She was still thinking about that exchange when she saw “Jews. In Their Own Words.” Late in the play, one character says that he thinks British Jews are just tired. That moment stuck with her. Maybe, she said, that was what had happened to her — after all this time, she was tired.

“Maybe I’ve got sick of listening to antisemitism,” she said. She was ready to talk. So, it seemed, were a lot of people.

Correction, October 5: A previous version of this story said the accent coach who first raised concerns about the name of Hershel Fink was told the character was not Jewish, which is incorrect: She says she was told he was modeled on Elon Musk, who is not Jewish.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO