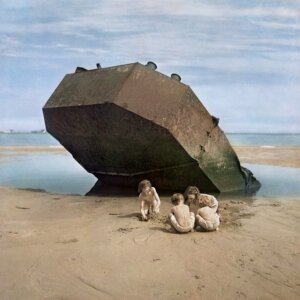

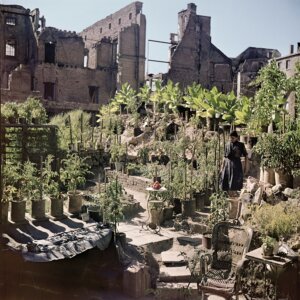

A risk-taking photographer who addressed his own suffering by documenting the sufferings of others

David ‘Chim’ Seymour captured images of refugee children, as well as Audrey Hepburn and Gina Lollobrigida

Tereska standing by her drawing of “home” in a home for emotionally disturbed children, in Warsaw, Poland, 1948. Courtesy of International Center of Photography

The Egyptian Jewish-born photography historian Carole Naggar has written a new book about the Polish Jewish photojournalist David Seymour (born Dawid Szymin), known as Chim. He was president of Magnum Photos, which he cofounded with his friend the Hungarian Jewish photographer Robert Capa and others. Chim, who is currently the subject of an exhibit at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, responded to the murder of his family in the Holocaust by working for UNICEF to document the sufferings of refugee children after World War II. Recently Naggar, a longtime resident of New York and Paris, whose latest work is “David ‘Chim’ Seymour: Searching for the Light — 1911-1956,” discussed with Benjamin Ivry the Yiddishkeit in Chim’s visual achievement.

Chim’s image, “Tereska, Who Was Raised in a Concentration Camp, Draws a Picture of ‘Home'” (1948), shows a young girl in a Warsaw orphanage who had suffered a war-related brain injury. Was there anything potentially intrusive or exploitative about its public display of symptoms of a vulnerable person, as in voyeuristic French Romantic portraits of mentally ill patients by Théodore Géricault, which inspired such later artists as the Belarusian Jewish painter Chaim Soutine?

It’s a bit of a loaded question; I’m not sure. When Chim went into the school, he had no clue that he would encounter someone like Tereska. He was photographing children in a row who had been assigned to draw a home, but what saves that picture from being intrusive or victimizing is that something passed between them. There was some sort of look between them and it seems to me that for a split second, Tereska was aware that someone was looking at her in a very deep sense. Because Chim himself was a traumatized person. He had learned a few months before that his entire family had been wiped out in the Holocaust. So he was able to make that picture in a way that was not abusive.

You quote the picture editor Jinx Rodger: “Like the wandering Jew, [Chim] seemed to carry the world upon his shoulders, but I suspect he was hiding his pleasure at going out on the job.” Chim was a human rights photographer, especially in his “Children of War” series, but was he more of a sensualist than is usually suspected? The German Jewish-born photographer Gisèle Freund said he was an ideal choice to take the portrait of the actress Anna Magnani since he had already photographed Sophia Loren, Ingrid Bergman, Joan Collins, Gina Lollobrigida and Audrey Hepburn. Even a Chim photo of the Lithuanian Jewish art historian Bernard Berenson, showing the nonagenarian ogling a marble sculpture in Rome’s Borghese Gallery, has a sybaritic side.

Oh, absolutely, I suspect he had adventures with a lot of the starlets he photographed. In his archives, there was a love letter from the Greek actress Irene Pappas. I don’t think Chim remained a monk for 30 years. He definitely had a sensual side with music, and played Chopin on the piano in a very effusive Romantic way. He was seen as an intellectual, and described as an owl or professor, but in some photos as a young man he looked more like a dreamer with a sensual mouth and eyes.

Chim’s father Benjamin Szymin, a friend of the writers Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Leon Feinberg and Borekh Glazman, ran a Warsaw syndicate that published Sholem Asch, among others. Was there anything overtly literary about Chim’s imagery? When Chim worked with the Italian Jewish author Carlo Levi to document illiteracy in Southern Italy, was his empathy with the subject the result of his own family’s literary activity or more generally, a reflection of the notion of Jews as People of the Book?

I agree with that completely. Reading and the book are themes in his work that go through like a thread. During the Spanish Civil War, [Chim] photographed a typewriter amidst debris. I think even in a deeper sense, his photographs are very literate and poetic and allusive, in a way that Capa’s images, for instance, are not.

Starting in the 1940s, you note, “Chim’s view of Israel was lyrical and romantic. Arabs almost never appeared in his stories, a striking omission … Chim also overlooked the violence that was necessary to establish and defend the Jewish state.” It must have been difficult to overlook the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Was Chim inured to violence due to his family being murdered by Nazis or was he resolved that Israel should exist at any cost?

I’m not sure it was a conscious thing. He was in a way blinded by his desire to find a new family and home beyond the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, so he lost some of his objectivity. Israel was the refuge and the dream, appealing to his sense for a community and common ideals until finally during the Suez Crisis of 1956, he photographed Egyptians as victims.

Chim was killed in Egypt shortly after the armistice of the Suez Crisis. At the time, some friends blamed Chim for taking undue risks. Yet must photojournalists who rush to capture human experience, like Robert Capa who stepped on a landmine in Vietnam or Capa’s German Jewish companion Gerda Taro, killed in the Spanish Civil War, expect to risk their lives?

I think it was part of the job. I don’t think there was a death wish there. There was a desire to reconnect with his youth and his work in the Spanish Civil War and a cause. He just did it. I don’t think there was a sense that he was taking risks he shouldn’t, even if friends observing him said he seemed oblivious to danger. But that’s what happens with photographers in war: they think they are protected by the camera, which doesn’t happen of course.

Chim was buried in Cedar Park and Beth El Cemeteries in Paramus, New Jersey, the resting place of Jewish authors such as Delmore Schwartz, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Ernst Cassirer, Eliezer Greenberg, and Maxwell Bodenheim. How did he wind up there? Did his family choose the Hebrew inscription on his gravestone?

I have absolutely no clue. New Jersey is where he started out in military service during the Second World War at Camp Edison, before he was assigned to be one of Ritchie Boys, a collection of soldiers trained to work as interpreters because they could speak several languages at Camp Ritchie in Maryland.

The printer Georges Fèvre told you in 2005 that “Esthetics was maybe not [Chim’s] first preoccupation” in photographing postwar orphans. Burt Glinn told you “I don’t think Chim ever thought about photography as fine art. He thought of it as a social instrument through which you could see social development.” But shouldn’t a photographic artist always be primarily concerned with the image?

I think [Chim] wanted the image to be a powerful tool and esthetics was one of the ways he did it. But I don’t think that the image itself was at the forefront of his thinking, the way it is for a lot of photographers today. He didn’t like people who were very pretentious about their photography. That really annoyed him. I think he would go nuts today in Paris, with some of the discourse that photographers have.

The exhibit “Chim: Between Devastation and Resurrection” runs through Feb. 4, 2024, at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $325,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO