The Nazis recorded everything they stole. One artist is mining their archives for something new.

Lisa Oppenheim’s solo exhibition inverts Nazi archival photos to make the absence of stolen objects and stolen lives feel tangible

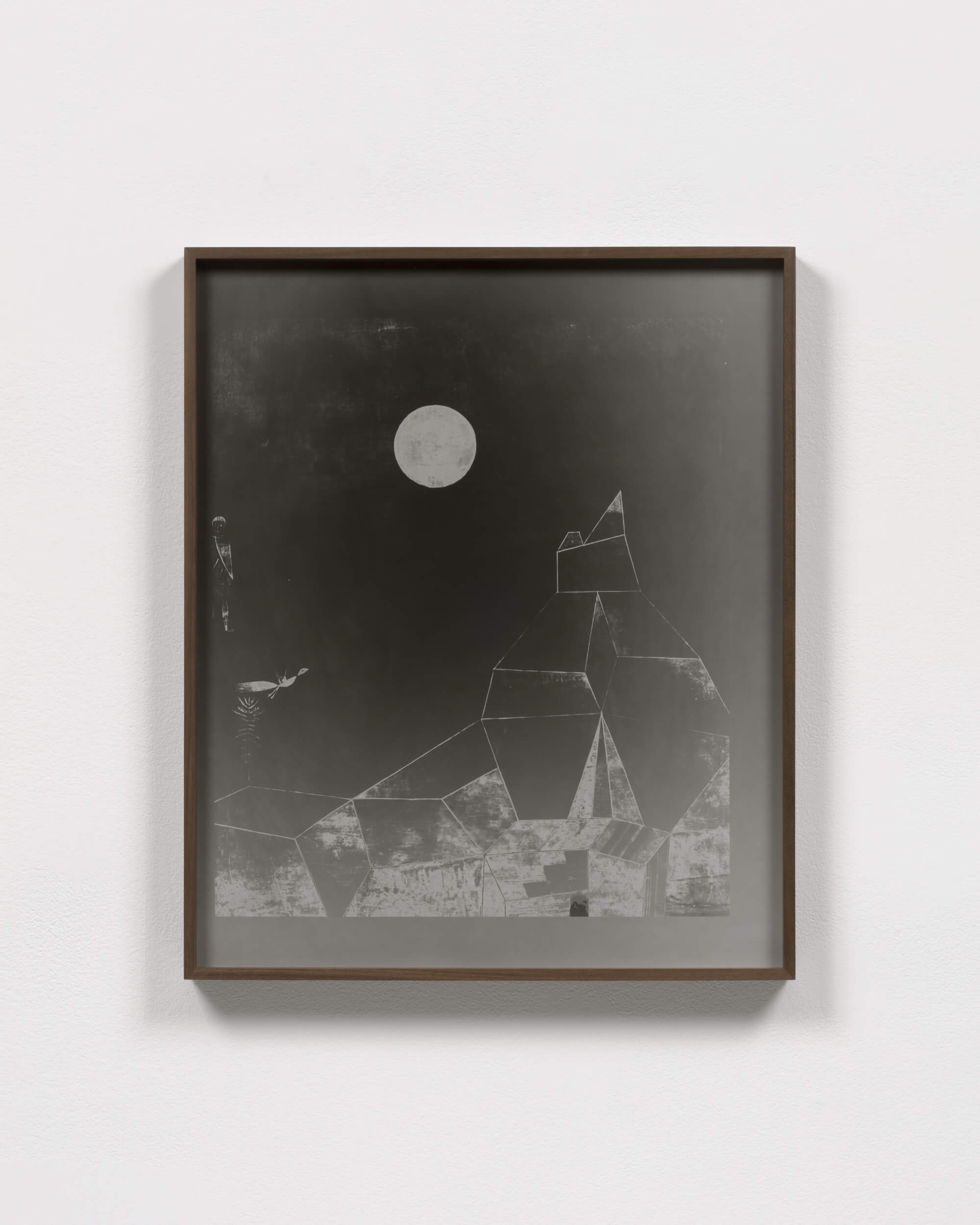

Courtesy of Lisa Oppenheim

It feels strange that the Nazis kept meticulous records of the objects and people they destroyed. Soldiers and guards noted the people they imprisoned, the supplies they were issued, how they died and even whether or not they had lice. And, of course, they recorded each possession they looted, neatly photographing paintings and sculptures, ceramics and even clothing for their archives.

These records, ironically, have helped to preserve the memory of the very people the Nazis sought to wipe out. Lisa Oppenheim, a 47-year-old multimedia artist from New York, dug into the archives for her new solo exhibition, “Spolia,” now on view at the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Manhattan. Redeveloping photos of items that have still never been found or restituted, Oppenheim brings light to the absence left in the wake of the Holocaust.

“Spolia,” a term for the practice of repurposing building stones for new structures, features new images from the Nazis’ archived negatives. During the development process, Oppenheim used firelight to overexpose, or solarize, the photos. The result is a harsh, scorched inverse of the lost pieces, printed at the same scale as the originals but rendered in stark black shadows.

The idea of inversion is central to the show; in addition to the solarized photos, there’s also a slideshow of photos Oppenheim took of porcelain molds used to produce German ceramics the Nazis were obsessed with collecting.

“The porcelain is made from this pristine white clay from German soil,” she told me over the phone the day after I visited the gallery. “So it fit into their whole narrative.”

Instead of focusing on the actual lost artworks — the details of which are hard to make out in the scorched images — the exhibition emphasizes absence, not only of the works themselves but of their original owners.

“I’m not trying to remake these artworks as they were or replace them into the world,” Oppenheim said. Instead, she sees herself as “bringing light to these images that would otherwise never be seen” — quite literally.

Oppenheim was living in Munich when she first conceived of the exhibit. The central city served as a hub for Nazi loot, which was brought there for sorting and storage. As a Jew, Oppenheim says she felt drawn not to the Michelangelos and Van Goghs the Nazis stole but to more plebeian pieces — small silver household items, ceramics and still lifes that reminded her of her grandparents’ house and decor.

One beaded shawl described in the archives even sounded similar to one the artist bought at a flea market years earlier, and though it is almost certainly not the same one lost to Nazi looting, Oppenheim included an image of her shawl in the exhibit, emphasizing the idea that every object has an unknown backstory.

While many exhibitions on lost art focus on the value of the pieces that were looted, Oppenheim wanted to distance the viewer from the works themselves and instead focus on who owned each painting. She doesn’t even list the artists’ names or the pieces’ titles, just the day it was photographed for the Nazi records and the accompanying archival description.

“I kind of wanted to leave the issue of authorship up in the air,” she said. “I didn’t use the title of the original painting. I was more interested in these as documentation images.”

Despite Oppenheim’s attempt to sidestep the specifics of each individual piece, the works she chose were some of those that Nazis most wanted to save. While the Third Reich sold off or destroyed works of modernist and abstract art the regime considered degenerate, still lifes fit with Hitler’s emphasis on classicism and realism. Some of the pieces Oppenheim used were confiscated by the Nazis for inclusion in the Fuhrermuseum, a planned — but never realized — Nazi museum celebrating Hitler’s cultural and artistic ideals, filled with looted artwork.

Still lifes by old masters, like those used in “Spolia,” fit perfectly with the Nazi artistic and cultural ideals. But it is in dialogue with this history that Oppenheim’s exhibit is most powerful. Her solarization technique inverts the classical, prosaic scenes into abstract, otherworldly images filled with abrupt lines and harsh shapes. It’s exactly the kind of thing the Nazis would have abhorred, and it feels like poetic justice.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO