Can you tell the entire history of antisemitism in just four episodes?

A new documentary strives to chronicle the story of the oldest hatred from antiquity to the 21st century

Windows of a Jewish-owned shop in Berlin, 1938. Photo by Getty Images

The ambitious four-part documentary, “Antisemitism: 2,000 Years of History” — produced by the Franco-German network Arte — explores the evolution of antisemitism from antiquity to the present. It considers how antisemitism has surfaced and reinvented itself, sometimes subtly, sometimes not so subtly, under Stalin and Hitler and against Alfred Dreyfus, Spinoza and others.

Throughout the ages, leaders have used antisemitism to divert attention from other crises by creating a scapegoat and uniting their citizens in common cause: blaming Jews.

Blood libel and the alleged conspiracy of wealthy Jews controlling the world are repeated themes. Deicide, the belief that the Jews killed Christ, still casts its ugly shadow in many quarters, though now anti-Zionism (often a thinly veiled code for antisemitism) has gained favor.

Still, Jews have been fully assimilated into the fabric of many societies for long stretches; that is, until they weren’t. Inevitably they’ve found themselves cast as tolerated outliers at best or demonized and dehumanized figures who should be annihilated, the latter view culminating in the Holocaust.

Jewish concerns are not new to director Jonathan Hayoun, who previously helmed the documentary “Saving Auschwitz.” In an email, he wrote to me that he has always “fought against antisemitism, particularly in my militant commitment when I was president of the union of Jewish students in France.”

His current project, which took several years to make, was labor intensive.

“It was first necessary to identify, with the co-writer Judith Cohen Solal, the decisive moments in the history of antisemitism and renounce the claim to exhaustiveness or objectivity in these choices,” Hayoun wrote. “The film highlights events that shed light on the evolution of a ‘total’ and global story. The series has received critical and public acclaim, especially among younger French viewers, many of whom saw it more than once.”

Still, the documentary does not address the basic question of why Jews have been consistently targeted, regardless of locale or era. Perhaps that can’t be answered. Also problematic is how the film telescopes major historical events throughout — though, given the breadth of the documentary, that’s arguably inevitable.

That said, the four-part series is consistently informative, engaging, and provocative. All the interviewees — from France, Germany, America and elsewhere — are erudite and accessible. Historians, psychoanalysts and theologians voice a range of perspectives on antisemitism.

The film is refreshingly devoid of manipulation, sentimentality and sensationalism. Its subject is treated matter-of-factly which affords the viewer the head space to absorb a body of knowledge, without heavy-handed and ultimately numbing biases.

The production, which interweaves interviews with photographs, archival footage and 3D historical reconstructions, is distinguished and classy. I was especially taken with the ultra-realistic 3D reconstructions of ancient Egypt and Paris during the French Revolution that were lifted from the action adventure video game “Assassin’s Creed.”

This is a rare instance, at least among documentaries that I’ve recently viewed, where mixed media snippets, including black ink drawings that evoke a graphic novel, are beautifully executed and integrated.

Episode I: The origin

Episode I begins in ancient Egypt where the first wave of antisemitic violence erupted. Four million Jews had lived peacefully and prosperously alongside Greeks, Romans and Egyptians in Alexandria for centuries. But when Egypt fell on hard times and Romans usurped its government, further exacerbating a collapsing economy and growing sense of despair, Jews were held responsible.

They were singled out as “different and privileged.” A new rumor surfaced: Jews were conducting human sacrifices in their synagogues in preparation for Passover, fattening up pagans for the kill. (Remember there were no Christians at this point.) Greek mobs pillaged the Jewish temples and attacked Jews who were burnt alive. They were forced to eat pork. If they refused, they were tortured and executed.

Antoine Guggenheim, a theologian and Catholic priest, says antisemitism didn’t really take root until the death of Christ and the birth of Christianity. Jews who rejected conversion were viewed as embodiments of evil. Psychoanalyst Alain Vanier suggests that in Christian mythology, there’s an inherent need to transfer evil in the world onto a specific individual or a group.

Still, circumstances might have been a lot worse had it not been for St. Augustine who argued that Jews deserved protection as “living fossils.” One pundit says if the saint had not taken that position — and if the powers that be did not go along with it — Jews might have disappeared from the earth.

Of the episodes, the first is the most difficult for contemporary viewers to grasp, not least for its depiction of an ancient world filled with almost unconnected regions; in each, Jews were experiencing their “otherness.”

Following Mohammed’s death in 632 as Islam spread throughout the Mideast, Jews were targeted. A similar phenomenon occurred in Spain, even as they moved up the hierarchy in many professions, including the military.

During the Crusades, thousands of warriors swept across the European Continent charging towards Jerusalem, first annihilating Muslims and then Jews with even more bloodthirsty fervor. A new canard surfaced: Jews had brought about their own victimhood.

One of the more striking episodes took place in Norwich, England, in 1144 when a lost boy’s battered body turned up in a nearby forest. It was widely believed that the boy was kidnapped by local Jews who tortured him in a ritual religious sacrifice.

Various paintings and sculptures of that time portrayed Jews savaging gentile children. The film’s selection of art is evocative in its reflection of the cultural views toward Jews who were increasingly seen as the servants of evil. The slow, systematic dehumanization of Jews had officially begun.

Episode II: Time of rejection

In the second episode, we’re reminded that until the year 1000 there was no earth-shattering difference between Jews and Christians in dress, customs or language. Neither baptisms nor circumcisions took place.

Christianity brought with it a seismic shift in the way Jews were seen. Short, dark-skinned Jews sporting hooked noses suddenly appeared in Christian art. Prior to 1160, Jews had not been distinguished by the shape of their noses in painting or sculpture.

As churches sprouted up across the continent and cities were built around those churches, royal and religious powers merged. Jews, viewed as “impure,” were segregated and forced to wear yellow circles on their clothes. Yellow was the color of the devil — all of it eerily foreshadowing the yellow stars European Jews displayed on their garments in pre-Holocaust ghettos and on their way to the death camps.

Still, Jews’ so-called “impurity” served a purpose. They could perform duties that Christians were not allowed to do. In England, that meant lending money and collecting taxes. Thus, the image of Jew as usurer and money fetishist was born. In 1190, a crowd in England attacked and killed more than 200 Jews.

Even after the Jews were expelled from England in 1290 (an expulsion that lasted 400 years) and Christian locals became the bankers, the portrayal of Jews as venal grotesques persisted in paintings, toys, games and passion plays. Until the 1990s, passion plays continued to feature Jews with horns.

Massive numbers of Jews converted to Christianity (in France, up to 80%) and they earned high positions within the church. But when one was appointed bishop, the backlash began. Spain refused to convert Jews. During the Inquisitions, which started in 1184, Christian warriors inspected chimneys on Friday nights assuming residents were observing Shabbat if their chimneys were smoke-free. As punishment, the Jews were burned to death in the town’s public square.

Ironically, during the 16th and 17th centuries, Poland was the most hospitable country to Jews. In the city of “Auschwitz,” which meant “guest,” Jews owned land, studied medicine and carried arms. Even so, antisemitism always lurked beneath the surface.

The film makes clear that history is not static. During the Age of Enlightenment, philosophers Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Denis Diderot openly debated the emancipation of Jews. Nevertheless, Jews were denied citizenship until Maximillian Robespierre reversed the narrative with his iconic and impassioned speech accusing the bigoted French public of the crimes with which they charged Jews. In the end all restrictions against Jews were lifted and they were granted full citizenship.

But at the very same time, new forms of hatred were fermenting.

Episode III: When hatred becomes racial

The French Revolution forged a heady sense of liberation for many Jews in France. In England, Jews did not fare as well, especially as the Industrial Revolution advanced and an exploited working class emerged.

Workers blamed their condition on Jews who became a symbol of exploitation. With the emergence of the Rothschilds in the 18th century, caricatures of well-heeled Jews, greedily clutching bags of money, were published, circulated and celebrated.

Simultaneously, an era of pseudo-science cropped up, most explicitly in the writings of French aristocrat Arthur-de-Gobineau, who theorized that Aryans were the superior race and Jews, whom he dubbed “Semites,” were a separate and inferior race.

When the eugenics movement was launched in 1883 by polymath Francis Galton, many politicians and thinkers of the era proudly branded themselves as antisemites. Religious bigotry had by no means disappeared, but political, economic and especially racial antisemitism had moved to the fore. Violence towards Jews escalated and a wave of pogroms washed over Russia and Poland.

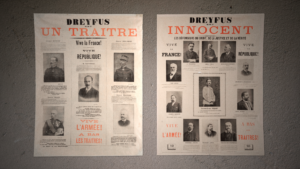

The Alfred Dreyfus affair unfolded in 1894. Dreyfus, a French Jewish artillery officer, was falsely convicted of treason and sentenced to life for smuggling military secrets to the Germans. Later, newer charges, based on forged documents, were brought against Dreyfus. The case split the nation and dragged on for 12 years.

Sarah Bernhardt and Anatole France defended Dreyfus. And novelist Emile Zola wrote his iconic open letter (“J’Accuse…!”) which forced France to acknowledge how antisemitism had led to a miscarriage of justice. Dreyfus was finally exonerated in 1906.

Thanks in part to the Dreyfus affair, Theodore Herzl, a Jewish Austrian writer and political activist wrote the work, “The Jewish State,” proposing the mass exile of Jews to their own autonomous homeland.

In the 1890s, hundreds of thousands of Jews left Russia for Palestine, America and elsewhere. Among those who remained, some were seduced by the growing Communist movement.

Many who previously labeled Jews as capitalist exploiters now accused them of being Communists. “The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion,” an anonymously written, virulently antisemitic text, published in 1903, explained how the Jews were planning to take over the world. It made no difference if the Jew was a capitalist exploiter or a Bolshevik agitator.

Still, there were novels, plays, and films that disparaged and satirized antisemitism. In the 1922 film, “The City Without Jews,” all Jews are expelled from Vienna until the citizens discover that, without scapegoats, the whole country falls apart. In the end the Jews are invited back.

Episode III goes on to trace the trajectory of Nazism and concomitant rise of antisemitism in Germany where Jews became a symbol of any cultural phenomenon the Germans disapproved. “Degenerate modern art” was deemed Jewish even though fewer than 5% of the artists in question were Jews. German universities were probed to make certain they were “appropriately German.”

In the wake of Kristallnacht in 1938 and the massive destruction of Jewish-owned stores and synagogues, thousands of Jews were shipped off to concentration camps.

At the end of the episode, novelist A.B. Yehoshua states, “Jews were not exterminated because of ideologies, economic or religious, but because Jews were simply microbes.”

Episode IV: The new faces of antisemitism

The iron gates of a concentration camp. Black smoke filling the sky. The silhouette of barracks devoid of life and train tracks overgrown with weeds leading to Auschwitz. These haunting images set the stage for Episode IV, which considers how antisemitism evolved in the post-Shoah world.

Following the war, between 300,000 and 400,000 Jews were “displaced persons,” until the birth of Israel in 1948. But the welcoming land of milk and honey would soon become the new centerpiece for, depending on your point of view, antisemitic or anti-Zionist hatred. From the outset, Israel was flanked on all sides by a hostile Arab world hellbent on Israel’s destruction, and they had their global supporters.

Though the USSR recognized the Jewish state, Golda Meir’s arrival as Israel’s ambassador to Russia marked the resurgence of antisemitism, especially when she visited a synagogue.

The episode turns its attention to World War II America, citing how many American-born Jews, like Philip Roth, grew up with a sense of national pride. Their Ashkenazi parents and grandparents (some of whom may have been pogrom or even Holocaust survivors) typically didn’t speak of their past experiences. The Jews were in the forefront of civil rights among other socially minded movements, and identified primarily as liberal Americans, not necessarily as Jews.

Ethnic identity politics, however, resurfaced during the 1961 Eichmann trial. For many Jews, this marked the first time they were forced to confront the enormity of the Holocaust.

On the cultural front, the horrors of antisemitism were explored in “The Diary of Anne Frank” (the memoir, the play and the film), André Schwarz-Bart’s novel “The Last of the Just,” and Claude Berri’s movie, “The Old Man and the Child,” which dramatized a friendship between a racist old man and a young Jewish boy.

At Vatican II in 1962, Pope John XXIII proclaimed that Jews were not responsible for the death of Christ.

Still, anti-Zionist sentiments were growing. In 1970 a nursing home in a Jewish Munich community was bombed. Two years later, 11 Israeli Olympic athletes were murdered by Palestinians in Munich. In 1975, the UN General Assembly condemned Zionism as a form of racism and racial discrimination. In 1991 the UN resolution was revoked, but the idea had taken hold.

While none of the interviewees in this documentary are apologists for antisemites on the left, they are much harsher on right-wing antisemitism. The most emotional segment occurs toward the end as Robert Badinter, the former French Minister of Justice and a Shoah survivor, testifies in the 2007 hearings against Holocaust denier Professor Robert Faurisson.

“You are a falsifier of history!” Badinter declares, his rage and anguish palpable as he recounts how his own family was exterminated in concentration camp gas chambers.

His raw personal testimony is all the more powerful because it’s an anomalous moment in an otherwise fact-driven film. Ironically it works, not because it’s cathartic but because it isn’t. There is no catharsis. There are no applicable lessons.

And that’s what emerges throughout the entire series. Antisemitism, its history, its future, is unique. Predictions cannot be made. Ingrained, pervasive and malleable, antisemitism remains one sly shape-shifter.

“Antisemitism: 2,000 Years of History” premieres Sept. 18 on ChaiFlicks.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO