Were the Three Stooges a lot more Jewish than we realized?

There’s a lot more to the comic trio’s Jewishness than the Yiddish they inserted in their skits

The Three Stooges in the short film “All Gummed Up.” From left: Larry Fine and Shemp and Moe Howard. Photo by Getty Images

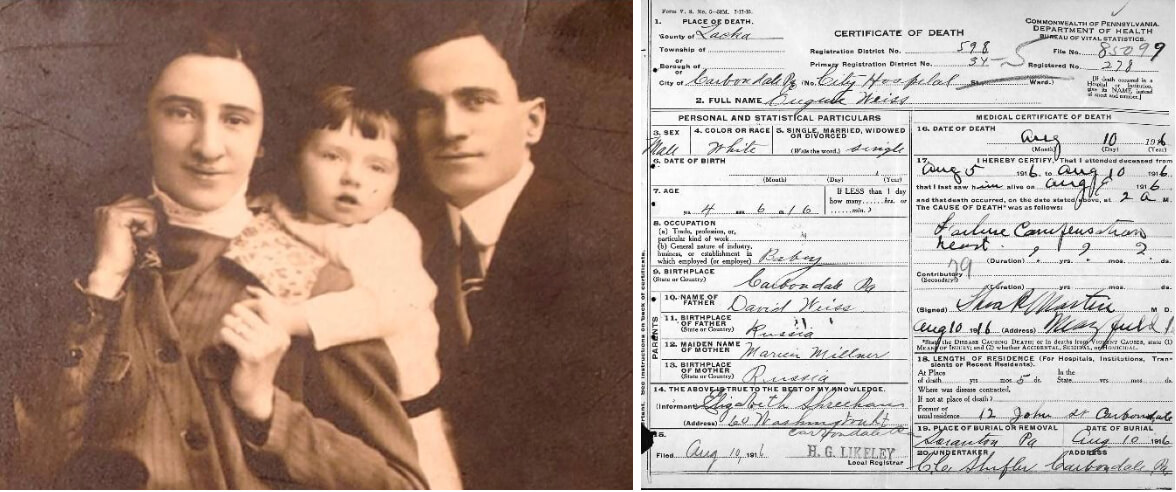

The news that the ketubah, or Jewish marriage contract, for Moe Howard from the Three Stooges has sold at auction for a hefty sum might provoke some reconsideration about the slapstick comedians’ Yiddishkeit.

Some Jews remain decidedly opposed to the eye-poking, nose-pulling, nyuk-nyuk-nyuk of violence that the Stooges meted out amongst themselves. Moe Howard (Moses Horwitz), his brothers Curly (Jerome Horwitz) and Shemp (Samuel Horwitz), and their friend Larry Fine (Louis Feinberg) continue to repel as well as amuse.

In a family reminiscence, the writer Joseph Epstein recalled how grappling with his brother during a dispute made them feel not like the biblical Cain and Abel or Esau and Jacob, but like “two of the Three Stooges.”

In February 1940, Sime Silverman’s “Variety,” the so-called showbiz bible, sniffed that the Stooges’ shtick was “informal, inane and uninhibited. It’s a series of eye-jabbing, head-thumping, nose-tweaking antics threaded on a string of rapid-fire chatter and embellished by double and triple takes.”

If taken seriously, this dismissal of the Stooges as violent and moronic would also mean jettisoning Laurel and Hardy among other ostensibly dim screen amusers.

Faye Ringel, an expert in comparative literature, has connected the Stooges to purimshpils, specifically in terms of what she calls the “tradition of the schlemiel and schlimazel.” Fools and jesters were time-honored Jewish roles in world theater, and Ringel categorized the Stooges according to Yiddish folklore as a schlemiel, schlimazel and persecutor.

Even if they epitomized the cruelty of the playground, the Stooges had the virtue of making a quantity of Yiddish audible to a wide audience. The Michigan journalist Allan Lengel recalled how, as a boy, hearing some Yiddish phrases in televised short films starring the Stooges made him realize “what a cool language Yiddish is.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Yqb14uoFLU

Gary Lassin, editor of The Three Stooges Journal, counted 38 Stooge short films containing Yiddish expressions. Still, Lillian Mermin Feinsilver, author of “The Taste of Yiddish,” castigated the Stooges’ use of the word farblondzhet (lost, mixed up) in a “synthetic transitive form”: “We’ll murder him. We’ll farblondzhe him.” Feinsilver reminded her readers, “the active verb, blondzhen, is intransitive, meaning ‘to wander, to lose one’s way.’ Farblondzhet is a past participle.”

Filmgoers with slightly lower grammatical expectations might chortle at the use of the term hakn a tshaynik (to bother someone) in 1936’s “A Pain in the Pullman,” Moe promises to hock or pawn some belongings and Larry retorts: “Hey, hock a chynick for me too, willya?”

With even more linguistic contortions, in “Mutts to You” from 1938, Larry, in yellowface as an Asian laundryman, offers doubletalk in the guise of Chinese speech with a dollop of Yiddish added, saying, “Hak mir nisht keyn tshaynik, and I don’t mean efsher” (“Stop bugging me, and I don’t mean maybe”)!

Perhaps the most pungent use of Yiddish as a reminder of identity was in the Stooges’ 1940 wartime comedy “You Nazty Spy!” in which Moe became the first American film comedian to dress up as Hitler, whom he oddly resembled. Not only did the Stooges’ spoof predate and outpower Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator,” open exclamations like “Beblach!” (Yiddish for beans) and “Shalom aleichem!” rendered explicit the message of Jewish comedians ridiculing Hitler.

During Moe’s mimicry of a Hitler speech, he says “in pupik gehabt haben” (“I’ve had it in the bellybutton”). Moe’s nonsense jabber imitating Der Fuehrer’s oratory has more devastating effrontery than Chaplin’s in “Great Dictator” or Tom Dugan’s as Bronski, an actor who masquerades as Hitler in Ernst Lubitsch’s 1942 film “To Be or Not to Be.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g3B2xeaJuhQ

As a Mussolini stand-in, Curly looks like a dimwitted hit man from “The Sopranos,” unlike the endearing comedian Billy Gilbert in the same role in Chaplin’s “Great Dictator.” Overall, “You Nazty Spy” communicated far more derision and loathing of Nazism than anything Chaplin could have devised, because the Little Tramp was created by a non-Jewish Englishman with intellectual pretensions. The Stooges, by contrast, were down and dirty, in addition to being frankly lowbrow.

More allusively, Freudian psychoanalysis, decried as a Jewish science by Nazis propagandists, was also lampooned in 1939’s “Three Sappy People,” in which the Stooges cure a mentally ill rich woman by inflicting a dose of their trademark lunacy on her. The implication is that during a deranged era of rising European fascism, insanity might be a potential panacea.

Woody Allen’s movie “Radio Days,” which evoked the same epoch, cites one comedian’s proposal that “to settle a war, the leaders of the countries involved should meet in a stadium and fight it out with socks filled with horse manure.” The Stooges’ sheer outlandish violence suited a moment of impending horror, just as Larry Fine’s expectation and acceptance of physical torment appeared to match a tradition of scapegoating Jews from the old country. The occasion was ripe for the Stooges, and recent historical events have not shown humanity in any more refined light.

Moe dressed up as Hitler yet again in 1943 in “They Stooge to Conga.” By then, they had won the hearts of many Jewish youths, not least Philip Roth, whose “Reading Myself and Others” lauds the Stooges as an influence for their “broadly comic” style.

Indeed, critics such as Morris Dickstein would pinpoint a quasi-terroristic Stooge-esque aggression in some Roth characters, like the quivering Jimmy Lustig in the novel “The Counterlife,” akin to Curly, impatient to perform some new outrage.

In parts of the world where vicious absurdity reigns, the Stooges, like Alfred Jarry’s Father Ubu, will always strike a chord of recognition. In the 1950s, Harvey Kurtzman’s editorship of Mad Magazine was inevitably inspired by the wildly flailing precedent of the Stooges.

And in 1968, a year of national torment, guitarist Ron Asheton of the burgeoning punk group The Stooges phoned Moe Howard to ask his permission to use their name for his band. Moe reportedly snapped: “I don’t care what they call themselves, as long as they’re not The Three Stooges!” and hung up. By not opposing the punks, a movement with much-noted Jewish participation, Howard revealed the ultimate anarchic comic virtue of not taking himself too seriously, unlike other grimly self-important professional clowns.

More recently, the Argentine Jewish novelist Alicia Borinsky’s “Mean Woman” (Mina Cruel) has been described as “worthy of the Three Stooges” in underlining comic elements amid brutality. The grandparents of Borinsky fled Russian pogroms over a century ago, only to encounter in their adopted land the torture of political prisoners and other human rights violations.

Today’s children routinely witness atrocities online that make the Stooges seem almost refined by comparison. A 2019 National Jewish Book Award-winning children’s book, “All Three Stooges” by Erica S. Perl, is about Noah Cohen, a seventh-grader obsessed by old comedy records and YouTube clips. The heartwarming story radiates a sentimentality required in this publishing genre that was notably absent from the merciless Stooges films at their early best.

Whether or not the Stooges will ever be universally accepted by discerning Jewish comedy fans, it may be time to consider shepping naches from Shemp Howard, his brother Moe, and their brethren as Jews who acted out risibly and derisively, making a lasting impact.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO