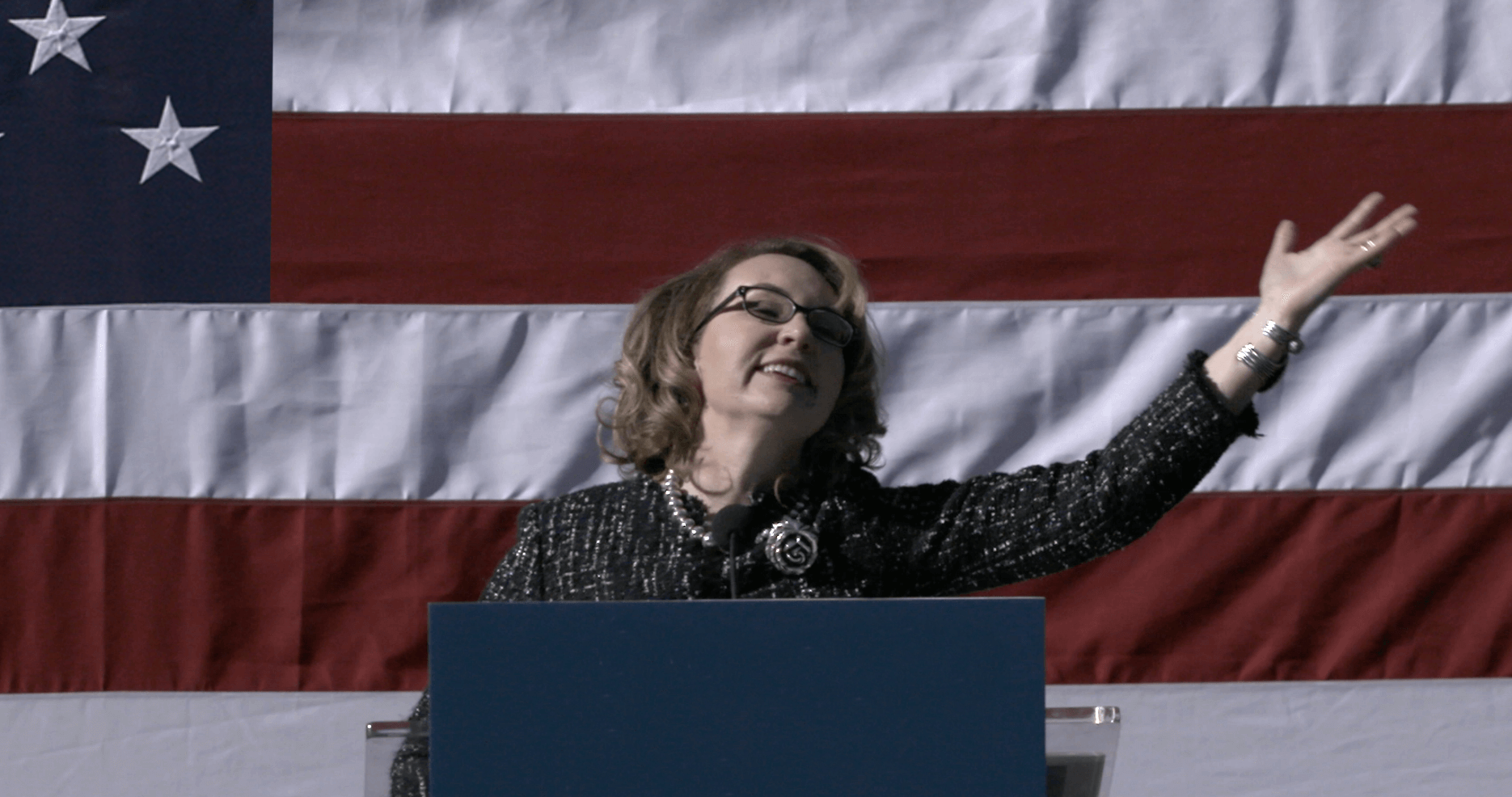

Against all odds, still Gabby Giffords persists and persists

A new documentary chronicles the improbable triumph of the former congresswoman from Arizona

Photo by Julie Cohen and Betsy West

On Jan. 8, 2011, Gabby Giffords, the well-liked and respected 41-year old Jewish Democratic congresswoman from Tucson, Arizona (and the first Jewish woman to hold that post), was gunned down at a meet-and-greet with her constituents in front of a suburban Safeway. The assassination attempt was almost successful. She was shot in the head and shortly thereafter mistakenly declared dead. Six others, including a 9-year-old child, were killed. Many others were injured.

Against all odds, Giffords survived, though she remains partially paralyzed on the right side and suffers from aphasia, a neurological condition that affects comprehension and speech. But thanks to her dogged perseverance coupled with the relentless loving support of her husband, astronaut Mark Kelly (who commanded several missions to the International Space Station), Giffords is out and about and very much in the public eye. She spearheaded Kelly’s successful campaign for Arizona’s U.S. Senate seat in 2020 (replacing the late John McCain) and she is a visible and outspoken advocate for gun control, among other progressive issues.

“Gabby Giffords Won’t Back Down” is a perfect title and boasts all the narrative elements to attract documentarians Betsy West and Julie Cohen, whose previous films centered on trailblazers Ruth Bader Ginsburg (“RBG”), Julia Child (“Julia”) and Pauli Murray (“My Name is Pauli”), the latter a civil rights activist, Episcopalian priest and a significant figure in the LGBTQ community.

Both Childs and Bader Ginsburg were also notable for having lucked into (or maybe consciously chosen) good-humored, feminist husbands who cared deeply about them. The same is exponentially true for Giffords, whose spouse is a super macho character, thus making him and their relationship that much more compelling.

Unlike the other films, however, this one lacks cohesiveness. Several thematic threads run concurrently, but don’t come together organically — her career and life trajectory; her enduring romance with Kelly; her medical ordeal chronicled in painstaking detail; and underlying all of this, a plea for gun control. At times, especially toward the end of the film, one suspects that the Giffords’ film was intended to serve in large measure a vehicle for the broader, undoubtedly timely, political purpose.

Both the opening and one of the final scenes features Giffords laying flowers at a cemetery (not clear where) for victims of gun violence. It’s as unsettling an image as it is visually riveting: perfectly formed rows of identical bouquets set in white vases spread across a large stretch of otherwise barren land. As the film progresses snippets of high-profile shootings and their aftermaths — Newtown, Connecticut (the Sandy Hook shooting); Las Vegas; Orlando — are interspersed. Oftentimes this can feel like a derailment, though admittedly not as much on the second viewing as on the first.

That said, there’s much to recommend here. Utilizing archival footage, home movies and ongoing conversations with Giffords, her husband, other family members and some political heavy hitters — among them, Barack Obama, Kirsten Gillibrand and Jim Clyburn — the film paints a vivid portrait of an unusual woman who, even as a youngster was an independent spirit, though according to her no-nonsense mom, a little bit of a goody two-shoes, especially when it came to monitoring the activities of her sister.

A horseback rider and a French horn player, Giffords graduated from Scripps College and later earned a master’s in regional planning from Cornell University before returning home to run her family-owned tire store, appearing in local TV commercials for it. Three years later, she sold it for a large sum of money.

Initially a registered Republican, she ultimately realized the more conservative views were not in sync with her own and she switched parties, becoming a centrist anti-abortion Democrat and a gun owner, but one who favors background checks. It is easy to see her appeal. She was — and still appears to be — upbeat, affable and engaging.

She launched her political career in the Arizona House of Representatives in 2001, moved up to become a member of the Arizona Senate, the youngest woman elected to that post. At the time of the shooting she was beginning her third term as a member of the U.S. Congress, by all accounts a rising star. Severely incapacitated, a year later, she bowed out.

She met Mark Kelly in 2003; they tied the knot in 2007 and had a long-distance marriage. While she was based in Tucson, he was operating out of Houston or Orlando. The film captures their chemistry and successful bond against all challenges, including his two grown daughters from his previous marriage, who did not appreciate Giffords’ presence in their dad’s life.

That changed after she was shot. They suddenly saw her in a more humanized light, one of the girls apologized in a heartfelt letter, and a genuine reconciliation with both stepdaughters ensued. It’s a rare stepfamily that seems to work.

Still, at 41, Giffords wanted her own child and was planning to go for in vitro fertilization on the Monday following the Saturday she was shot. This was one dream that never reached fruition. Yet at no point does she appear bitter about it.

Kelly was at her bedside throughout her long and arduous rehabilitation. Shortly before he retired from NASA in order to take care of her full time, he was off in space while she was undergoing emergency surgery to relieve a water build up on her brain. His mission was life-threatening, but what she faced, he concluded, was far more dangerous.

in a scene from “Gabby Giffords Won’t Back Down.” Photo by Dyann Taylor

At every point along the way, Kelly was videotaping her struggle and recovery. With her head shaved, looking like a lost child as she lay in an oversized hospital bed, Giffords was in no position to give informed consent. Much of this discomfiting and, yes, fascinating footage is incorporated into the film. Neither Kelly nor her parents ever abandoned her — her mother appeared healthy and engaged throughout while her ailing dad, a wheelchair user, sat off to the back alone, immobilized and silent. At moments the family portrait can be both unnerving and surreal.

One can see Giffords’ frustration as she desperately tries to create a vocal sound. For long stretches of time she can produce puffs of air, but little more. The patience and compassion of her speech therapists is remarkable. Music therapy helps, bringing to mind Oliver Sacks who pointed out that even the most brain-damaged patients can be aided with music, which for a variety of complex neurological reasons boosts memory and other motor skills.

Giffords favors the pop tunes of the ’80s, specifically The Talking Heads, U2 and Tom Petty, whose song, “I Won’t Back Down,” speaks to her on many fronts and contributes to the film’s sound score (not to mention its title). She’s able to sing a few words and slowly, very slowly, learns to vocalize words. The process has its comic moments. Even Giffords laughs at herself aware that she cannot stop repeating the word “chicken.”

After months of grueling speech, medical, and physical therapy Giffords returns home, improved in ways no doctor anticipated. She rides around the neighborhood on an adaptive bike, a tricycle for adults with special needs. And, more heartwarming, we see her mentoring Kelly as he prepares to give his maiden speech as state senator. He is in public office almost as a stand-in for Giffords and he needs her to instruct him in the finer points of public speaking. She urges him to stand up straight: “Posture, posture,” she tells him.

Though the film does unravel a bit toward its conclusion it is nonetheless an inspiring story of resiliency and determination. Giffords’ moving observation that “even if you struggle to speak, you still have a voice” resonates.

In 2020, at the age of 50, Giffords had a bat mitzvah, a development that begs for elaboration that does not materialize. It would have been interesting to know how her Jewish identity evolved in the wake of the shooting, and on the flip side, how being Jewish informed, if it did, her interpretation of the shooting and its torturous aftermath.

Still, watching her bike down the streets singing is uplifting, even if her choice of music might not necessarily be to your taste. The film concludes on a note of hope, optimism and a wonderfully defiant affirmation of life.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO