In ‘Gefilte Fish,’ a metaphor for once and future trauma

In her art, Yuliya Lanina addresses the silence surrounding the Holocaust and the war in Ukraine

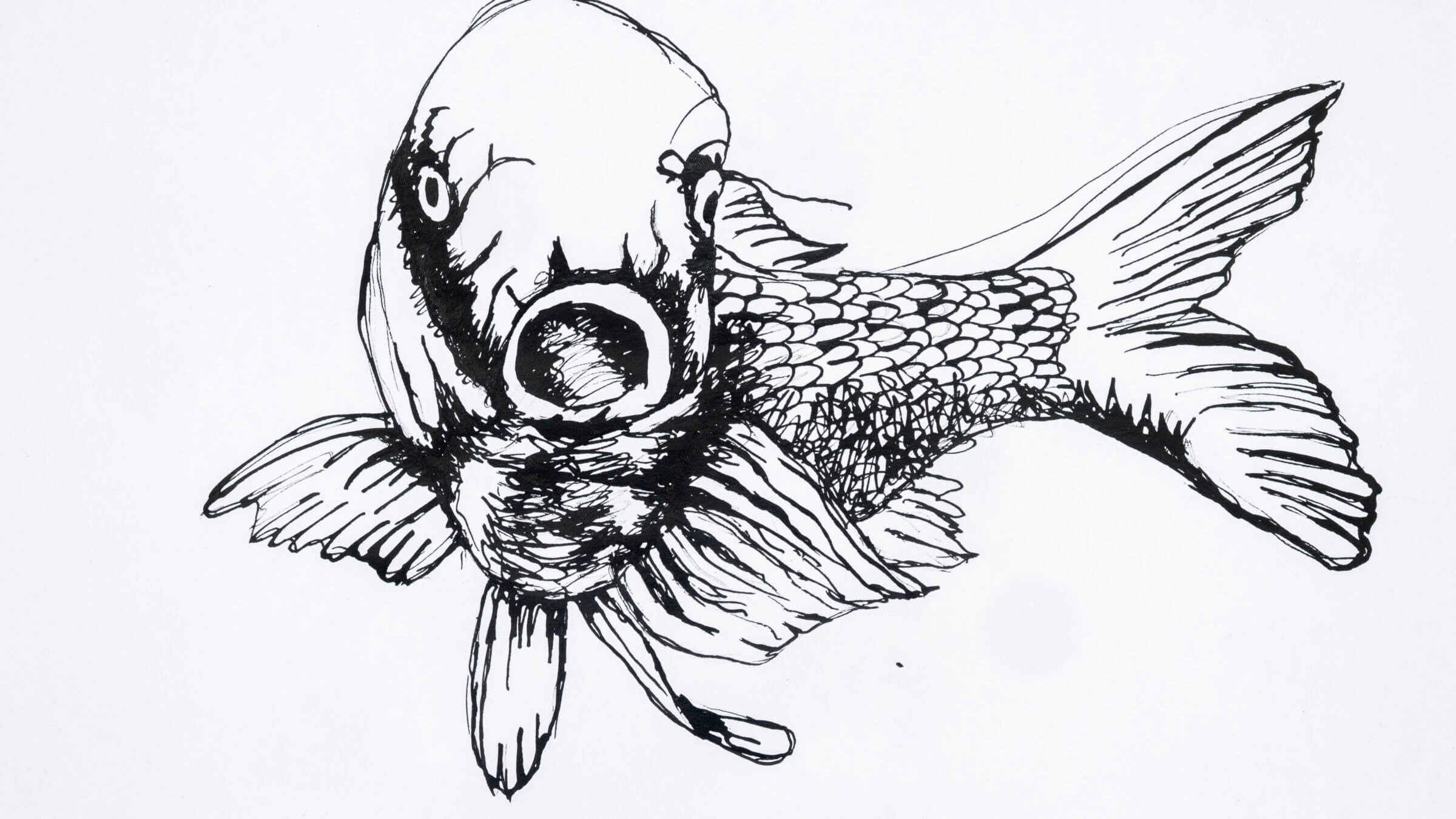

For Yulia Lanina, the titular ‘gefilte fish’ is really about being gutted by collective and familial trauma and spilling one’s guts. by Yulia Lanina

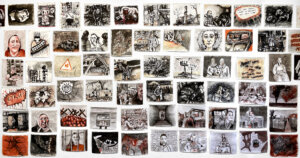

The walls of artist Yuliya Lanina’s studio in South Austin are covered floor to ceiling with small ink drawings. Rendered in black and white, but tinged (and sometimes splashed or soaked) with red, they depict the effects of Russia’s continuing and brutal war in Ukraine. Smoke, blood, tears.

Lanina is a petite woman with a head of unruly black curls and dark brown eyes, which, when speaking about Ukraine, express frustration, anger and deep sorrow. A multimedia artist of Jewish-Russian-Ukrainian descent, she is known for creating intricate colorful, and otherworldly paintings, animatronics, animations and installations.

Her drawings of Ukraine, however, are simple, stark and quickly rendered in response to the numerous images of destruction circulated daily via press and social media. Lanina’s father was from Ukraine; her mother was from Moscow.

“This war is like a war between my parents,” she told me. “It affects me deeply. These drawings are illustrations of my heartbreak as I bear witness from afar to the horrors of this senseless war.”

Before the war began, Lanina was preparing for an Austin exhibition titled “Guts,” featuring the stop-motion animation “Gefilte Fish.” The film, which emerged during Lanina’s residency, supported by a Fulbright fellowship, at the MuseumsQuartier Vienna in 2021, is an autobiographical saga that moves between a family dinner in the Bronx in the 1990s and a small village in Ukraine 50 years prior. Lanina came to the United States from Moscow when she was a teenager to study art. Her parents arrived the following year, part of a large exodus of Jews from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. During this gap year, Lanina was abused by a relative. The film begins with the artist, then suffering from an eating disorder, unable to eat the gefilte fish her mother, ill with cancer, has lovingly prepared for her.

We see a plated fish, rotating as if on a lazy susan. Panning out, the fish becomes the pupil within a large eye, which then shifts to a self-portrait of the artist, emaciated, stripped down, hair shorn, against a background of dark angry scribbles that evoke barbed wire.

“You’re like a prisoner in Auschwitz,” her father says, teasing her. “All skin and bones. All you can see is the eyes.”

“Gefilte” means stuffed in Yiddish. Unlike the fish balls traditionally eaten on Passover, making gefilte fish from scratch requires deboning and gutting a fish, filling the intact fish skin with minced and seasoned fish meat, baking it, and finally, serving the stuffed fish whole. This story may begin with the artist unable to eat the meal her mother has made her, but it is really about being gutted by collective and familial trauma and spilling one’s guts as a means to counter the silences that enable such violence to recur.

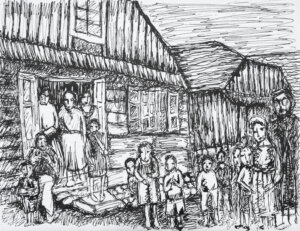

In 1941, Lanina’s grandmother, father, and uncle miraculously survived the slaughter of all the Jews in their shtetl, Chudnov, which is about halfway between Kyiv and Lviv. The “Holocaust by bullets,” as it has come to be known, was the first phase of the Final Solution. The most infamous massacre occurred in September 1941 at Babyn Yar, when the SS shot and killed 33,771 Jews over two days, burying them in a mass grave. The Nazis buried children alive so as not to waste bullets, a horrifying image that Lanina illustrates in the animation by depicting mounds of earth that heave and swell. After the war, the Soviet Union suppressed this history by marking mass graves, if they were marked at all, as the resting place of “Soviet” citizens rather than Jews. Such erasure helped enforce a culture of silence for Soviet Jews as a means of survival.

“Silence!” Lanina shouts in the animation, echoing her grandparent’s warning about how to exist in the Soviet Union. “Let’s not speak about the past. We must survive as a family. No Yiddish in the house. We must adapt.” This silence and silencing continued to haunt the artist’s family, even after they had left the Soviet Union and had settled in the United States.

Through her art, however, Lanina demands that we see and hear. Her work illustrates what historian Marianne Hirsch terms postmemory, the connection that children or grandchildren of survivors bear to a history that they never experienced but one that weighs on them nonetheless. Faced with reticence about the past, second- or third-generation survivors seek to understand this inherited legacy of trauma through creative means.

The images in “Gefilte Fish” —the fish who appears to be screaming silently, the haunted and vacant eyes of prisoners in Auschwitz, matter-of-fact depictions of what happened in Chudnov — are rendered in black and white because Lanina views the Holocaust as an emotional black hole, a void impossible to represent. The use of black and white also references old family photographs, and the ways in which we view the past from a distance. The animation is set to music by Austin-based composer Sam Lipman, whose grandfather managed to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto, but lost his parents and 12 (of his 13) siblings. His haunting music adds an additional layer to the story, connecting us to different times and places.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, Lanina saw history repeating itself. “I went into shock,” she said. “Instead of keeping the war in my brain, I started putting it on the page.” She has titled her new series of drawings “My Wailing Wall,” referencing the Western Wall in Jerusalem’s Old City, where people leave prayers tucked inside stones. She depicts the faces of survivors — an old woman mourning; women cleaning up rubble; a man seated among body bags; people excavating ruins, hiding in shelters, waiting for evacuation.

To some of these images, she adds in layers of blurred handwriting to record witness accounts, the number of children dead, and her own thoughts and feelings. She also portrays courageous Ukrainian fighters and volunteers, as well as people in Russian cities protesting the invasion. We see destroyed buildings, damaged Holocaust memorials (like the one recently built in Kharkiv), abandoned cars riddled with bullets, toys without children, smoke, fire — the residues of war. She does not, however, depict the dead, who she says, “didn’t give consent to what happened to their bodies.” The drawings now fill the walls of the local gallery, where “Gefilte Fish” is also on display.

To Lanina, the images in “Gefilte Fish” and “My Wailing Wall” represent the convergence of past and present: the sadistic machinery of war, genocide, sexual violence, the danger of nationalist narratives voiced by dictators and autocrats, the suppression of history and free speech. Through her art, Lanina hopes to counter silence and passivity. About Ukraine, she says, “You must not look away. When something so horrific is happening and it’s too painful to comprehend or to see, one must see and comprehend.”

Rebecca Rossen, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of “Dancing Jewish: Jewish Identity in American Modern and Postmodern Dance” (Oxford University Press). Her current research focuses on Holocaust representation in performance and media.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO