Mira Lehr’s art grapples with climate change and environmental destruction. Somehow, it’s still optimistic.

The Miami-based artist sees the rising ocean levels in her own yard. But even as her art shows the dangers of climate destruction, she still has hope we can turn it around.

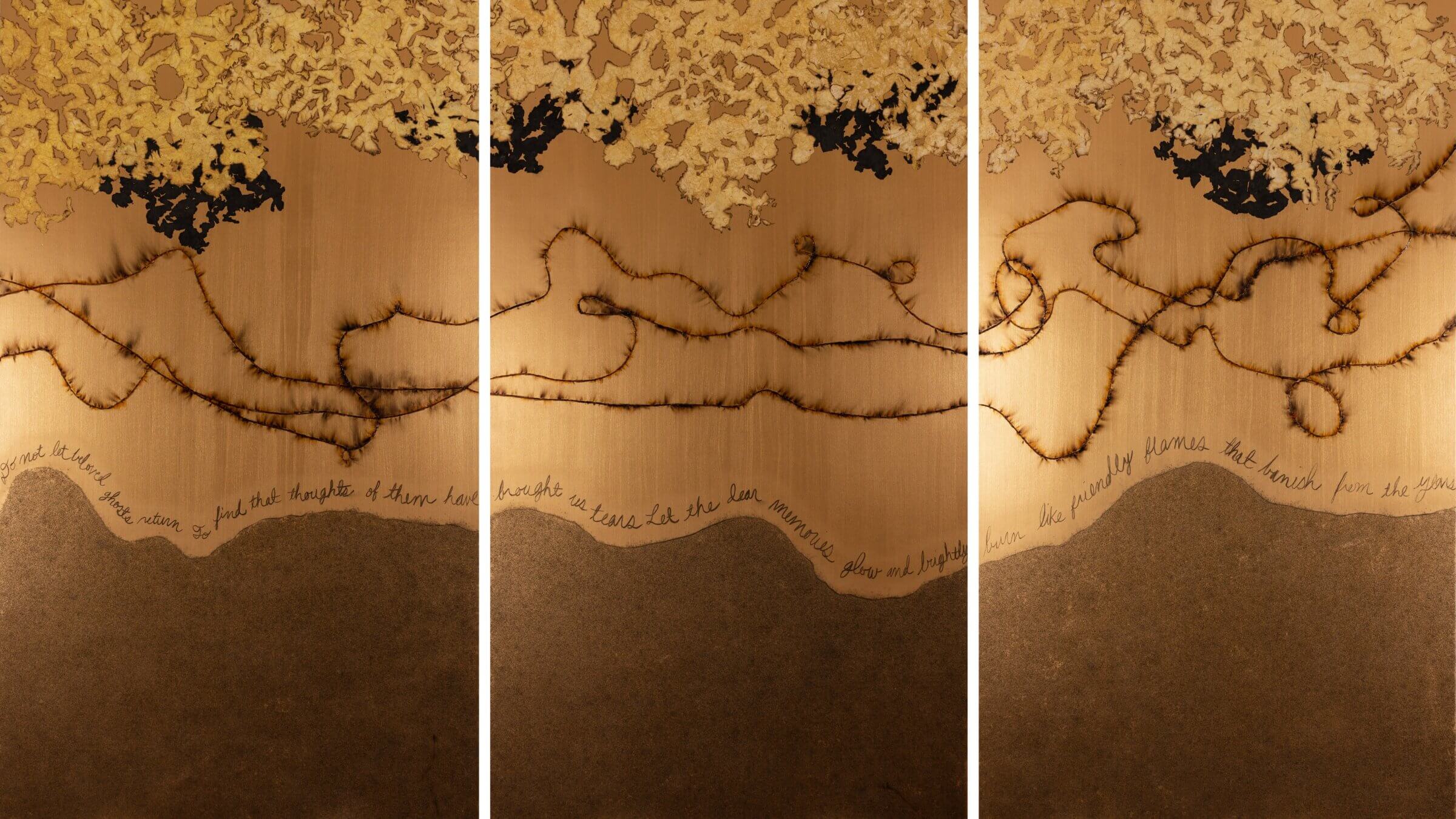

“Her Golden Hour,” one of Lehr’s pieces in the newest exhibition. Image by Mira Lehr

The artist Mira Lehr has always been ahead of the curve — she founded Continuum, one of the first women’s art collectives in the U.S., and was a pioneer in Miami’s art scene, working to bring notable artists down to participate in what was then a fledgling endeavor.

And, decades before environmental activism became mainstream, she began making work about our need for sustainability.

As a young artist, one year before the first Earth Day, Lehr was invited to participate in futurist thinker Buckminster Fuller’s “World Game” project, in which Fuller gathered a group of 26 people from a wide range of disciplines to experiment with ideas for solving the world’s issues on a game board. The experience — as well as her residence in Miami, a city already impacted by climate change — led Lehr to increasingly focus on sustainability and the environment in her artwork.

Today, Lehr is known for her leadership in both environmental activism and in promoting women in the art world.

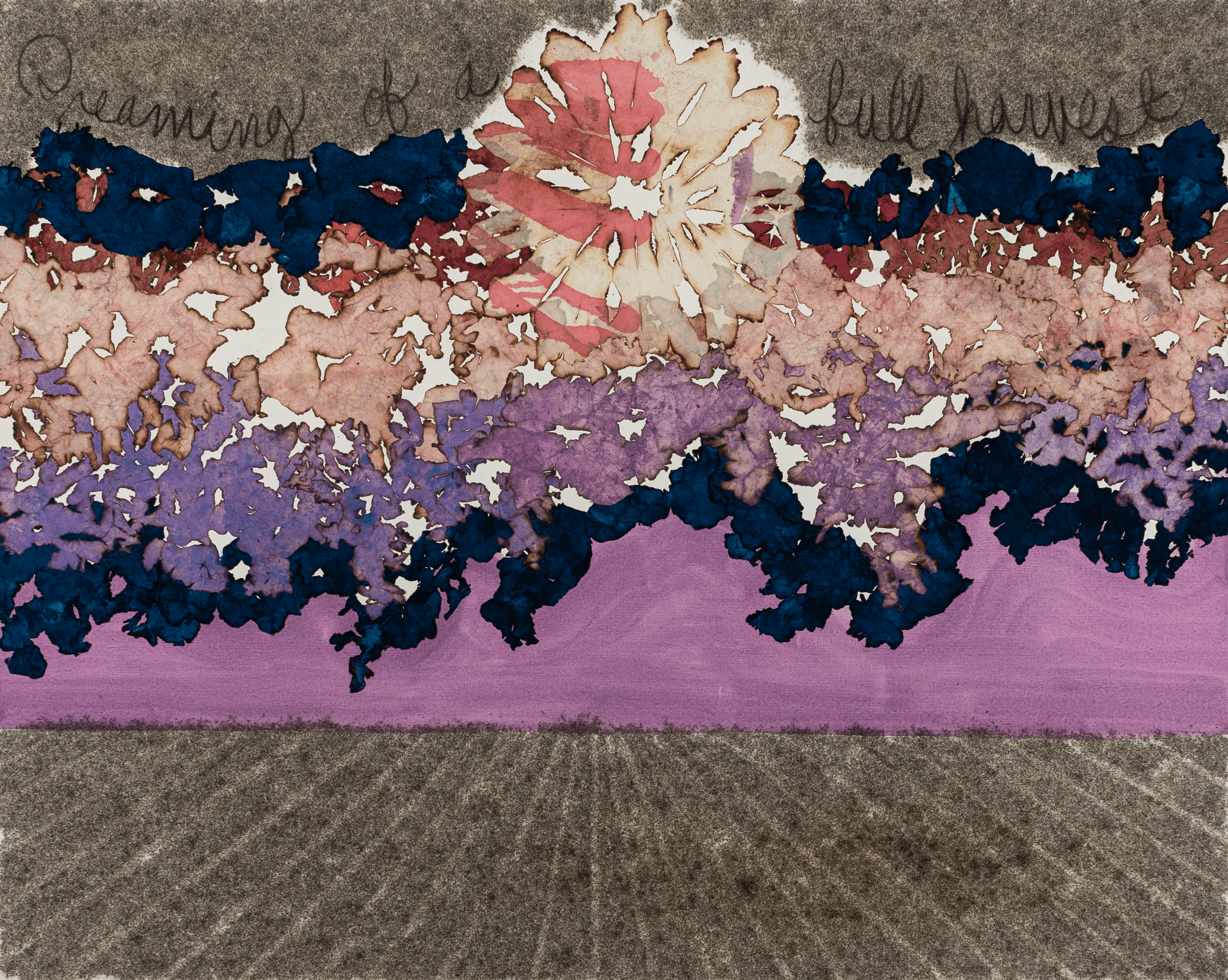

And she’s just become the subject of a new tome from SKIRA Editore, a major arthouse, detailing her body of work.The publishers might have gotten ahead of themselves: Even at age 87, Lehr is not done yet. She has a new exhibit at the EPIC Klimpton Hotel in Miami, showcasing artwork she made during the pandemic. As new problems of all varieties — ecological, political, pathogenic — have loomed during the past two years, the eco-feminist artist has been hard at work in her Miami studio, turning those fears into works of art. The result is work that is abstract and intuitive, combining soft natural forms with harsh lines that urgent warn viewers of the dangers facing the world. Yet her pieces retain a beauty that speaks of persistent hopefulness and optimism.

When I spoke with Lehr over Zoom, she sat at a stately wooden desk covered with books and art materials. The wall behind her was filled with stylized portraits — her own work, in a mode far different from her current, abstract and natural style.

You’re described as an “eco-feminist.” I’m curious how those two ideas connect for you.

It’s not a name I thought of myself — it was given to me. And I understand why. I have always been for women in art. I wasn’t a militant feminist, but i was a verbal and pictorial one. So I did a lot of work promoting women’s causes through my art.

And the ecology thing happened after I worked with Bucky Fuller in 1969, when I became very concerned about the future of our planet.

What was it like being a woman artist at that time?

It was terrible. Period. Women were not thought of as artists. Firstly, being a woman was against you, secondly if you were married and had children, that certainly made you a dilettante. And if you lived in Miami Beach, forget it — no one ever took us seriously. And we were a serious group.

Tell me about your time with Buckminster Fuller.

It was when we had the first moon landing, that’s when I was working on the World Game with Bucky Fuller. I left my family and the kids and went to New York because I had this wonderful opportunity — I had to miss one kid’s graduation from grammar school, but, you know, she survived.

That time with Bucky made a big difference in my life. I was one of only two artists.

Were you already working with environmental themes?

No. I worked with nature — I always loved it. But I wasn’t aware of the precarious position the earth world would be in if we didn’t shape up. “Doing more with less” is the major concept we learned. So it was sustainability, all these things that mean so much now, and doing more with less meant that the earth could survive if we became more efficient.

I learned with Fuller, studying Japan, that in one year they imported and exported the same amount of rice. We could never figure out why. But that’s the kind of thing I became aware of, that kind of wastefulness and not using things to their greatest potential.

How did you develop your current style?

Well, you know, you evolve. Early on, I didn’t have that much training, I wasn’t thinking about what I was doing.

And then, as I evolved, I had more training, more luggage — or baggage, I should say. I started to go through many different phases. First you start not knowing anything, then you start learning about too much, and then you have to shed it all and get to where you are.

Your current work has these delicate, floral elements, and then you have the burn marks from the gunpowder you’ve been working with since 1969. What message are you trying to convey with that contrast?

I’m trying to convey creation and destruction and take the bloom off the rose. The art is beautiful to look at — but I don’t want it to be about that. By introducing fire and almost blowing up everything, sometimes to the point of losing it, I think that adds an element of danger and destruction that I think is important.

Wow — have you lost any pieces to the gunpowder?

I used to — and a few eyelashes. I got to know how to use it better, but in the beginning, it was a little uncontrolled and scary. It’s still quite dramatic to watch, but now I can control it. I have to do it outside, because there’s a lot of smoke, and the gunpowder just booms up, all at once, and the cloud of smoke is amazing.

All of my neighbors think I’m crazy because they don’t know exactly what I”m doing but they see smoke rising from my yard. The fuse is burned in little increments, they travel up the painting, and it leaves sharp imagery of thorns coming out of it. It’s almost like barbed wire. So it’s another image that brings some negative force to the work — the idea of destruction.

I’m curious about that imagery of destruction. I could imagine that coming from humanity’s destructive tendencies toward the world, but also the world has earthquakes and tornados, its own fickle and destructive nature.

Actually, it’s very interesting that you combine the two — that’s exactly what it’s about. I didn’t think of it until you just mentioned it, but it is exactly. The earth has its own destructive potential, and we also can add to it with what we do, so it’s always a balance of not going too far. We are on a ticking clock, really — if we go too far, we’ve lost it, and the earth will not continue.

But I’m hoping that we’ll get it together as time goes on. I think it’s like 30 years — if we’re still burning fossil fuels, we will have had it. Then the environment won’t correct. So I’m trying to bring out the message, too: “Stop using fossil fuels.”

All of the pieces in your current exhibition are from the past few years, all made during the pandemic. What was your creative process during this time? What kinds of questions were inspiring you during this strange period?

Well, it was strange in a way, but for me, I’m always indoors, I’ve never been one to be out roaming around very much, and I’m used to being alone. So it came very naturally for me to just continue doing what I was doing.

What changed is my fears about things happening on the planet and the future of the environment, and how the world was going to be, and how viable it would remain or not remain. So those concerns were new.

There’s clearly an activist message in your work. How do you think art works in activism?

I just feel that when people see an image, it’s a real, intense feeling that they get when they see something rather than read about it. So I think when they see something blow up, or catch fire, it leaves a very deep impulse in them of danger, let’s get out of here, what’s going wrong.

Have you heard of the shmita year? In the bible, it says every seven years, the seventh year is to be a year of rest and you let the fields lie fallow and regenerate. This year is a shmita year, and I found it very fitting for your art.

I like that concept – I have to learn how to spell that. I’d like to do work about that.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO